Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is a disease caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum.[2] Symptoms of this infection vary greatly, but the disease affects primarily the lungs.[3] Occasionally, other organs are affected; this is called disseminated histoplasmosis, and it can be fatal if left untreated.

| Histoplasmosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cave disease,[1] Darling's disease,[1] Ohio valley disease,[1] Reticuloendotheliosis,[1] Spelunker's lung and Caver's disease |

| |

| Histoplasma capsulatum. Methenamine silver stain showing histopathologic changes in histoplasmosis | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Histoplasmosis is common among AIDS patients because of their suppressed immunity.[4] In immunocompetent individuals, past infection results in partial protection against ill effects if reinfected.

Histoplasma capsulatum is found in soil, often associated with decaying bat guano or bird droppings. Disruption of soil from excavation or construction can release infectious elements that are inhaled and settle into the lung.

From 1938 to 2013, a total of 105 U.S. outbreaks were reported in 26 states and the territory of Puerto Rico. From 1978 to 1979, during a large urban outbreak (100,000 victims) of the disease in Indianapolis, victims had pericarditis, rheumatological syndromes, esophageal and vocal cord ulcers, parotitis, adrenal insufficiency, uveitis, fibrosing mediastinitis, interstitial nephritis, intestinal lymphangiectasia, and epididymitis. Histoplasmosis mimics colds, pneumonia, and the flu, and can be shed by bats in their feces.

Signs and symptoms

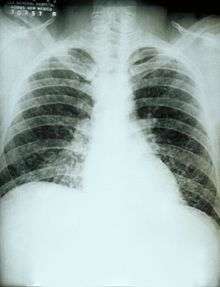

If symptoms of histoplasmosis infection occur, they will start within 3 to 17 days after exposure; the average is 12–14 days. Most affected individuals have clinically silent manifestations and show no apparent ill effects. The acute phase of histoplasmosis is characterized by non-specific respiratory symptoms, often cough or flu-like. Chest X-ray findings are normal in 40–70% of cases.[5] Chronic histoplasmosis cases can resemble tuberculosis;[6][7] disseminated histoplasmosis affects multiple organ systems and is fatal unless treated.[8]

While histoplasmosis is the most common cause of mediastinitis, this remains a relatively rare disease. Severe infections can cause hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and adrenal enlargement.[3] Lesions have a tendency to calcify as they heal.

Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS) causes chorioretinitis, where the choroid and retina of the eyes are scarred, resulting in a loss of vision not unlike macular degeneration. Despite its name, the relationship to Histoplasma is controversial.[9][10] Distinct from POHS, acute ocular histoplasmosis may rarely occur in immunodeficiency.[11][12]

Complications

In absence of proper treatment and especially in immunocompromised individuals, complications can arise. These include recurrent pneumonia, respiratory failure, fibrosing mediastinitis, superior vena cava syndrome, pulmonary vessel obstruction, progressive fibrosis of lymph nodes. Fibrosing mediastinitis is a serious complication and can be fatal. Smokers with structural lung disease have higher probability of developing chronic cavitary histoplasmosis.

After healing of lesions, hard calcified lymph nodes can erode the walls of airway causing hemoptysis.

Mechanisms

H. capsulatum grows in soil and material contaminated with bird or bat droppings (guano). The fungus has been found in poultry house litter, caves, areas harboring bats, and in bird roosts (particularly those of starlings). The fungus is thermally dimorphic: in the environment it grows as a brownish mycelium, and at body temperature (37 °C in humans) it morphs into a yeast. Histoplasmosis is not contagious, but is contracted by inhalation of the spores from disturbed soil or guano.[3] The inoculum is represented principally by microconidia. These are inhaled and reach the alveoli.

In the alveoli, macrophages ingest these microconidia. They survive inside the phagosome. As the fungus is thermally dimorphic, these microconidia are transformed into yeast. They grow and multiply inside the phagosome. The macrophages travel in lymphatic circulation and spread the disease to different organs.

Within the phagosome the fungus has an absolute requirement for thiamine.[13] Cell-mediated immunity for histoplasmosis develops within 2 weeks. If the patient has strong cellular immunity, macrophages, epithelial cells and lymphocytes surround the organisms and contain them, and eventually calcify. In immunocompromised individuals, the organisms disseminate to different organs such as bone, spleen, liver, adrenal glands and mucocutaneous membranes, resulting in progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. Chronic lung disease can manifest.

Diagnosis

Clinically, there is a wide spectrum of disease manifestation, making diagnosis somewhat difficult. More severe forms include: (1) the chronic pulmonary form, often occurring in the presence of underlying pulmonary disease; and (2) a disseminated form, which is characterized by the progressive spread of infection to extra-pulmonary sites. Oral manifestations have been reported as the main complaint of the disseminated forms, leading the patient to seek treatment, whereas pulmonary symptoms in disseminated disease may be mild or even misinterpreted as flu.[14] Histoplasmosis can be diagnosed by samples containing the fungus taken from sputum (via bronchoalveolar lavage), blood, or infected organs. It can also be diagnosed by detection of antigens in blood or urine samples by ELISA or PCR. Antigens can cross-react with antigens of African histoplasmosis (caused by Histoplasma duboisii), blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, and talaromycosis infection. Histoplasmosis can also be diagnosed by a test for antibodies against Histoplasma in the blood. Histoplasma skin tests indicate whether a person has been exposed, but do not indicate whether they have the disease.[3] Formal histoplasmosis diagnoses are often confirmed only by culturing the fungus directly.[4] Sabouraud agar is one type of agar growth media on which the fungus can be cultured. Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated disease are diverse and often present as a nondescript rash with systemic complaints. Diagnosis is best established by urine antigen testing, as blood cultures may take up to 6 weeks for diagnostic growth to occur and serum antigen testing often comes back with a false negative before 4 weeks of disseminated infection.[15]

Prevention

It is not practical to test or decontaminate most sites that may be contaminated with H. capsulatum, but the following sources list environments where histoplasmosis is common, and precautions to reduce a person's risk of exposure, in the three parts of the world where the disease is prevalent. Precautions common to all geographical locations would be to avoid accumulations of bird or bat droppings.

The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) provides information on work practices and personal protective equipment that may reduce the risk of infection.[17] This document is available in English and Spanish.

A review paper exists which includes information on locations in which histoplasmosis has been found in Africa (in chicken runs, on bats, in the caves bats infest, and in soil), and a thorough reference list including English, French, and Spanish language references.[18]

Treatment

In the majority of immunocompetent individuals, histoplasmosis resolves without any treatment. Antifungal medications are used to treat severe cases of acute histoplasmosis and all cases of chronic and disseminated disease. Typical treatment of severe disease first involves treatment with amphotericin B, followed by oral itraconazole.[19][20]

Liposomal preparations of amphotericin B are more effective than deoxycholate preparations. The liposomal preparation is preferred in patients that might be at risk of nephrotoxicity, although all preparations of amphotericin B have risk of nephrotoxicity. Individuals taking amphotericin B are monitored for renal function.[21]

Treatment with itraconazole will need to continue for at least a year in severe cases,[22] while in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, 6 to 12 weeks treatment is sufficient. Alternatives to itraconazole are posaconazole, voriconazole, and fluconazole. Individuals taking itraconazole are monitored for hepatic function.

Prognosis

90% of patients with normal immune system will gain health without any intervention. Less than 5% will need serious treatments.

Epidemiology

Histoplasmosis capsulatum is found throughout the world. It is endemic in certain areas of the United States, particularly in states bordering the Ohio River valley and the lower Mississippi River. The humidity and acidity patterns of soil are associated with endemicity. Bird and bat droppings in soil promote growth of Histoplasma. Contact with such soil aerosolizes the microconidia, which can infect humans. It is also common in caves in southern and East Africa. Positive histoplasmin skin tests occur in as many as 90% of the people living in areas where H. capsulatum is common, such as the eastern and central United States.[3]

In Canada, the St. Lawrence River Valley is the site of the most frequent infections, with 20–30 percent of the population testing positive.[23]

A review of reported cases in 2018 showed disease presence throughout South East Asia [24]

In India, the Gangetic West Bengal is the site of most frequent infections, with 9.4 percent of the population testing positive.[25] Histoplasma capsulatum capsulatum was isolated from the local soil proving endemicity of histoplasmosis in West Bengal.[26]

History

Histoplasma was discovered in 1905 by Samuel T. Darling,[27] but was only discovered to be a widespread infection in the 1930s. Before then, many cases of histoplasmosis were mistakenly attributed to tuberculosis, and patients were mistakenly admitted to tuberculosis sanatoriums. Some patients contracted tuberculosis in these sanatoriums.[28]

Society and culture

- Johnny Cash included a reference to the disease, even correctly noting its source in bird droppings, in the song "Beans for Breakfast".[29]

- Bob Dylan was hospitalized due to histoplasmosis in 1997, causing the cancellation of concerts in the United Kingdom and Switzerland.[30]

- In episode 21 of season 3 of the television series House M.D., a patient was diagnosed with histoplasmosis.

- In episode 5 of season 1 of the television series Dexter, Vince Masuka gets worried about getting histoplasmosis from the dust in the air and the hair of the rats.

- In episode 5 of season 5 of Monsters Inside Me Cody Fry became infected with histoplasmosis.

- In episode 1 of season 2 of the television series Billy the Exterminator, histoplasmosis is mentioned as possible infections from bats in an attic and their droppings.

- In How Clean Is Your Crime Scene? Neil tells one of his employees that they could get histoplasmosis if they don't wear a respirator.

- In episode 3 of season 1 of the television series Emily Owens, M.D., a patient was diagnosed with histoplasmosis.

References

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- Stenn, Frederick (1960). "Cave Disease or Speleonosis". American Medical Association Internal Medicine. 105 (2): 181–183. doi:10.1001/archinte.1960.00270140003001.

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 674–6. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- Cotran RS, Kumar V, Fausto N, Robbins SL, Abbas AK (2005). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. St. Louis: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 754–5. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- Silberberg P (2007-03-26). "Radiology Teaching Files: Case 224856 (Histoplasmosis)". Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- Tong P, Tan WC, Pang M (1983). "Sporadic disseminated histoplasmosis simulating miliary tuberculosis". Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 287 (6395): 822–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.287.6395.822. PMC 1549119. PMID 6412842.

- Gari-Toussaint, Marty P, Le Fichoux Y, Loubière R (1987). "Histoplasmose d'importation à Histoplasma capsulatum, données biocliniques et thérapeutiques variées, à propos de trois cas observés dans les Alpes maritimes". Bull Soc Fr Mycol Med. 16 (1): 87–90.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kauffman, CA (January 2007). "Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (1): 115–132. doi:10.1128/CMR.00027-06. PMC 1797635. PMID 17223625.

- Thuruthumaly C, Yee D. C., Rao P. K. (2014). "Presumed ocular histoplasmosis". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 25 (6): 508–12. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000100. PMID 25237930.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Nielsen J. S., Fick T. A., Saggau D. D., Barnes C. H. (2012). "Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for choroidal neovascularization secondary to ocular histoplasmosis syndrome". Retina. 32 (3): 468–72. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e318229b220. PMID 21817958.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Macher A, Rodrigues M. M., Kaplan W, Pistole M. C., McKittrick A, Lawrinson W. E., Reichert C. M. (1985). "Disseminated bilateral chorioretinitis due to Histoplasma capsulatum in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome". Ophthalmology. 92 (8): 1159–64. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33921-0. PMID 2413418.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gonzales, C. A.; Scott, I. U.; Chaudhry, N. A.; Luu, K. M.; Miller, D; Murray, T. G.; Davis, J. L. (2000). "Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by Histoplasma capsulatum var. Capsulatum: A case report and literature review". Ophthalmology. 107 (4): 725–9. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00179-7. PMID 10768335.

- Garfoot AL, Zemska O, Rappleye CA (2013) Histoplasma capsulatum depends on de novo vitamin biosynthesis for intraphagosomal proliferation. Infect Immum

- Brazão-Silva MT, Mancusi GW, Bazzoun FV, Ishisaaki GY, Marcucci M. A gingival manifestation of histoplasmosis leading diagnosis. Contemp Clin Dent. V.4 (1). 2013 (http://www.contempclindent.org/text.asp?2013/4/1/97/111621)

- Rosenberg JD, Scheinfeld NS (December 2003). "Cutaneous histoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome". Cutis. 72 (6): 439–45. PMID 14700213.

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- "NIOSH Publications and Products - Histoplasmosis - Protecting Workers at Risk (2005-109)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 2004. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2005109. Retrieved 13 August 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gugnani, HC; Muotoe-Okafor, F (1997). "African histoplasmosis: a review" (PDF). Rev Iberoam Micol. 14 (4): 155–159. PMID 15538817.

- Wheat L. J.; Freifeld A. G.; Kleiman M. B.; et al. (2007). ""Infectious Diseases Society of America (2007). "Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 45 (7): 807–25. doi:10.1086/521259. PMID 17806045.

- Histoplasmosis: Fungal Infections at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Home Edition

- Moen, M. D.; Lyseng-Williamson, K. A.; Scott, L. J. (2009). "Liposomal amphotericin B: A review of its use as empirical therapy in febrile neutropenia and in the treatment of invasive fungal infections". Drugs. 69 (3): 361–92. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969030-00010. PMID 19275278.

- Barron MA, Madinger NE (November 18, 2008). "Opportunistic Fungal Infections, Part 3: Cryptococcosis, Histoplasmosis, Coccidioidomycosis, and Emerging Mould Infections". Infections in Medicine.

- "Histoplasmosis". www.ccohs.ca. Canadian Centre for Occupational Health & Safety. July 1, 2013.

- Baker J, Setianingrum F, Wahyuningsih R, Denning DW. Mapping histoplasmosis in South East Asia–implications for diagnosis in AIDS. Emerging microbes & infections. 2019 Jan 1;8(1):1139-45.

- Sanyal M, Thammayya A (1975). "Histoplasma capsulatum in the soil of Gangetic Plain in India". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 63 (7): 1020–8. PMID 1213788.

- Sanyal M., Thammayya A. (1980). "Skin sensitivity to histoplasmin in Calcutta and its neighbourhood". Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 46 (2): 94–98. PMID 28218139.

- Darling ST (1906). "A protozoan general infection producing pseudotubercles in the lungs and focal necrosis in the liver, spleen and lymphnodes". J Am Med Assoc. 46 (17): 1283–5. doi:10.1001/jama.1906.62510440037003.

- Bennett J.E.; Dolin R.; Blaser M.J. "Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases" 8ed September 11, 2014 ISBN 978-1455748013

- Kroll, David (6 March 2014). "Solving The Mystery Of 'Bamboo Bonfire' Lung Disease". Forbes. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

- CNN - Bob Dylan hospitalized with Histoplasmosis Archived 2007-10-26 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |