Pityriasis rosea

Pityriasis rosea is a type of skin rash.[2] Classically, it begins with a single red and slightly scaly area known as a "herald patch".[2] This is then followed, days to weeks later, by a pink whole body rash.[3] It typically lasts less than three months and goes away without treatment.[3] Sometime a fever may occur before the start of the rash or itchiness may be present, but often there are few other symptoms.[3]

| Pityriasis rosea | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pityriasis rosea Gibert[1] |

| |

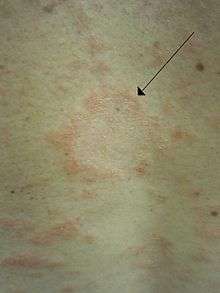

| Pityriasis rosea on the back | |

| Specialty | Dermatology, Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Single red and slightly scaly area, followed |

| Usual onset | 10 to 35 years old[2] |

| Duration | Less than three months[2] |

| Causes | Unclear[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Tinea corporis, viral rash, pityriasis versicolor, nummular eczema[3] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[3][2] |

| Frequency | 1.3% (at some point in time)[3] |

While the cause is not entirely clear, it is believed to be related to human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6) or human herpesvirus 7 (HHV7).[3] It does not appear to be contagious.[3] Certain medications may result in a similar rash.[3] Diagnosis is based on the symptoms.[2]

Evidence for specific treatment is limited.[3] About 1.3% of people are affected at some point in time.[3] It most often occurs in those between the ages of 10 and 35.[2] The condition was described at least as early as 1798.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of this condition include:

- An upper respiratory tract infection may precede all other symptoms in as many as 69% of patients.[4]

- A single, 2- to (rarely) 10-cm oval red "herald" patch appears, classically on the abdomen.[5] Occasionally, the "herald" patch may occur in a 'hidden' position (in the armpit, for example) and not be noticed immediately. The "herald" patch may also appear as a cluster of smaller oval spots, and be mistaken for acne. Rarely, it does not become present at all.

- 7–14 days after the herald patch, many small (5–10 mm) patches of pink or red, flaky, oval-shaped rash appear on the torso. The more numerous oval patches generally spread widely across the chest first, following the rib-line in a characteristic "christmas-tree" distribution. Small, circular patches may appear on the back and neck several days later.[5]

- In 6% of cases an "inverse" distribution may occur, with rash mostly on the extremities.[6] In children, presentation can be atypical or inverse, and the course is typically milder.[7][8]

- About one in four people with PR have mild to severe symptomatic itching. (Moderate itching due to skin over-dryness is much more common, especially if soap is used to cleanse the affected areas.) The itching is often non-specific, and worsens if scratched. This tends to fade as the rash develops and does not usually last through the entire course of the disease.[9]

- The rash may be accompanied by low-grade fever, headache, nausea and fatigue.[10]

Causes

The cause of pityriasis rosea is not certain, but its clinical presentation and immunologic reactions suggest a viral infection as a cause. Some believe it to be a reactivation[11] of herpes viruses 6 and 7, which cause roseola in infants.[12][13][14][15]

Diagnosis

Experienced practitioners may make the diagnosis clinically.[16] If the diagnosis is in doubt, tests may be performed to rule out similar conditions such as Lyme disease, ringworm, guttate psoriasis, nummular or discoid eczema, drug eruptions, other viral exanthems.[16][17] The clinical appearance of pityriasis rosea is similar to that of secondary syphilis, and rapid plasma reagin testing should be performed if there is any clinical concern for syphilis.[18] A biopsy of the lesions will show extravasated erythrocytes within dermal papillae and dyskeratotic cells within the dermis.[16]

A set of validated diagnostic criteria for pityriasis rosea[19][20] is as follows:

A patient is diagnosed as having pityriasis rosea if:

- On at least one occasion or clinical encounter, he / she has all the essential clinical features and at least one of the optional clinical features, and

- On all occasions or clinical encounters related to the rash, he / she does not have any of the exclusional clinical features.

The essential clinical features are the following:

- Discrete circular or oval lesions,

- Scaling on most lesions, and

- Peripheral collarette scaling with central clearance on at least two lesions.

The optional clinical features are the following:

- Truncal and proximal limb distribution, with less than 10% of lesions distal to mid-upper-arm and mid-thigh,

- Orientation of most lesions along skin cleavage lines, and

- A herald patch (not necessarily the largest) appearing at least two days before eruption of other lesions, from history of the patient or from clinical observation.

The exclusional clinical features are the following:

- Multiple small vesicles at the centre of two or more lesions,

- Two or more lesions on palmar or plantar skin surfaces, and

- Clinical or serological evidence of secondary syphilis.

Treatment

The condition usually resolves on its own, and treatment is not required.[21] Oral antihistamines or topical steroids may be used to decrease itching.[16] Steroids do provide relief from itching, and improve the appearance of the rash, but they also cause the new skin that forms (after the rash subsides) to take longer to match the surrounding skin color. While no scarring has been found to be associated with the rash, scratching should be avoided. It's possible that scratching can make itching worse and an itch-scratch cycle may develop with regular scratching (that is, you itch more because you scratch, so you scratch more because you itch, and so on). Irritants such as soaps with fragrances, hot water, wool, and synthetic fabrics should be avoided. Lotions that help stop or prevent itching may be helpful.[21][22]

Direct sunlight makes the lesions resolve more quickly.[16] According to this principle, medical treatment with ultraviolet light has been used to hasten resolution,[23] though studies disagree whether it decreases itching[23] or not.[24] UV therapy is most beneficial in the first week of the eruption.[23]

A 2007 meta-analysis concluded that there is insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of most treatments.[25] Oral erythromycin was found to be effective for treating the rash and relieving the itch based on one early trial; however, a later study could not confirm these results.[4][25][26]

Prognosis

In most patients, the condition lasts only a matter of weeks; in some cases it can last longer (up to six months). The disease resolves completely without long-term effects. Two percent of patients have recurrence.[27][28]

Epidemiology

The overall prevalence of PR in the United States has been estimated to be 0.13% in men and 0.14% in women. It most commonly occurs between the ages of 10 and 35.[16] It is more common in spring.[16]

PR is not viewed as contagious,[29][30] though there have been reports of small epidemics in fraternity houses and military bases, schools and gyms.[16]

See also

- Pityriasis circinata - a localized form of pityriasis rosea that affects the axillae and groin

- Pityriasis - for list of similarly named flaky skin conditions

- List of cutaneous conditions

References

- Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L.; Rapini, Ronald P. (2003). Dermatology. Mosby. p. 183. ISBN 9789997638991.

- "Pityriasis Rosea". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Eisman, S; Sinclair, R (29 October 2015). "Pityriasis rosea". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 351: h5233. doi:10.1136/bmj.h5233. PMID 26514823.

- Sharma PK, Yadav TP, Gautam RK, Taneja N, Satyanarayana L (2000). "Erythromycin in pityriasis rosea: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 42 (2 Pt 1): 241–4. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90132-4. PMID 10642679.

- González, Lenis M.; Allen, Robert; Janniger, Camila Krysicka; Schwartz, Robert A. (2005-09-01). "Pityriasis rosea: An important papulosquamous disorder". International Journal of Dermatology. 44 (9): 757–764. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02635.x. ISSN 1365-4632. PMID 16135147.

- Tay YK, Goh CL (1999). "One-year review of pityriasis rosea at the National Skin Centre, Singapore". Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 28 (6): 829–31. PMID 10672397.

- Trager, Jonathan D. K. (2007-04-01). "What's your diagnosis? Scaly pubic plaques in a 2-year-old girl--or an "inverse" rash". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 20 (2): 109–111. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2006.12.005. ISSN 1083-3188. PMID 17418397.

- Chuh, Antonio A. T. (2003-11-01). "Quality of life in children with pityriasis rosea: a prospective case control study". Pediatric Dermatology. 20 (6): 474–478. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2003.20603.x. ISSN 0736-8046. PMID 14651563.

- "Pityriasis rosea". American Academy of Dermatology. 2003. Archived from the original on 2009-06-21. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- Parsons, Jerome M. (1986-08-01). "Pityriasis rosea update: 1986". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 15 (2): 159–167. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70151-5. ISSN 0190-9622.

- Board basics : an enhancement to MKSAP 17. Alguire, Patrick C. (Patrick Craig), 1950-, Paauw, Douglas S. (Douglas Stephen), 1958-, American College of Physicians (2003- ). [Philadelphia, Pa.]: American College of Physicians. 2015. ISBN 978-1938245442. OCLC 923566113.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Drago F, Broccolo F, Javor S, Drago F, Rebora A, Parodi A (2014). "Evidence of human herpesvirus-6 and -7 reactivation in miscarrying women with pityriasis rosea". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 71 (1): 198–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.023. PMID 24947696.

- http://www.dermnetnz.org/viral/pityriasis-rosea.html%5B%5D

- Pityriasis Rosea at eMedicine

- Cynthia M. Magro; A. Neil Crowson; Martin C. Mihm (2007). The Cutaneous Lymphoid Proliferations: A Comprehensive Textbook of Lymphocytic Infiltrates of the Skin. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-0-471-69598-1. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- Habif, Thomas P (2004). Clinical Dermatology: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy (4th ed.). Mosby. pp. 246–8. ISBN 978-0-323-01319-2.

- Horn T, Kazakis A (1987). "Pityriasis rosea and the need for a serologic test for syphilis". Cutis. 39 (1): 81–2. PMID 3802914.

- Board basics : an enhancement to MKSAP 17. Alguire, Patrick C. (Patrick Craig), 1950-, Paauw, Douglas S. (Douglas Stephen), 1958-, American College of Physicians (2003- ). Philadelphia, Pa.: American College of Physicians. 2015. ISBN 978-1938245442. OCLC 923566113.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Chuh AA (2003). "Diagnostic criteria for pityriasis rosea: a prospective case control study for assessment of validity". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 17 (1): 101–3. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00519_4.x. PMID 12602987.

- Chuh A, Zawar V, Law M, Sciallis G (2012). "Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, pityriasis rosea, asymmetrical periflexural exanthem, unilateral mediothoracic exanthem, eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a brief review and arguments for diagnostic criteria". Infectious Disease Reports. 4 (1): e12. doi:10.4081/idr.2012.e12. PMC 3892651. PMID 24470919.

- Chuh, A.; Zawar, V.; Sciallis, G.; Kempf, W. (2016-10-01). "A position statement on the management of patients with pityriasis rosea". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV. 30 (10): 1670–1681. doi:10.1111/jdv.13826. ISSN 1468-3083. PMID 27406919.

- Browning, John C. (2009-08-01). "An update on pityriasis rosea and other similar childhood exanthems". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 21 (4): 481–485. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832db96e. ISSN 1531-698X. PMID 19502983.

- Arndt KA, Paul BS, Stern RS, Parrish JA (1983). "Treatment of pityriasis rosea with UV radiation". Archives of Dermatology. 119 (5): 381–2. doi:10.1001/archderm.119.5.381. PMID 6847217.

- Leenutaphong V, Jiamton S (1995). "UVB phototherapy for pityriasis rosea: a bilateral comparison study". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 33 (6): 996–9. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90293-7. PMID 7490372.

- Chuh, AA; Dofitas, BL; Comisel, GG; Reveiz, L; Sharma, V; Garner, SE; Chu, F (18 April 2007). "Interventions for pityriasis rosea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005068. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005068.pub2. PMID 17443568.

- Rasi A, Tajziehchi L, Savabi-Nasab S (2008). "Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea". J Drugs Dermatol. 7 (1): 35–38. PMID 18246696.

- Kempf W, Adams V, Kleinhans M, Burg G, Panizzon RG, Campadelli-Fiume G, Nestle FO (1999). "Pityriasis rosea is not associated with human herpesvirus 7". Archives of Dermatology. 135 (9): 1070–2. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.9.1070. PMID 10490111.

- Chuang TY, Ilstrup DM, Perry HO, Kurland LT (1982). "Pityriasis rosea in Rochester, Minnesota, 1969 to 1978". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 7 (1): 80–9. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(82)80013-3. PMID 6980904.

- "Pityriasis rosea". American Osteopathic College of Dermatology. Retrieved 26 Jan 2010.

- "Pityriasis rosea". DERMAdoctor.com. Archived from the original on 2009-04-08. Retrieved 26 Jan 2010.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |