Terminal nerve

The terminal nerve, or cranial nerve zero, was discovered by German scientist Gustav Fritsch in 1878 in the brains of sharks. It was first found in humans in 1913.[1] A 1990 study has indicated that the terminal nerve is a common finding in the adult human brain.[2][3] The nerve has been called by other names, including cranial nerve XIII, Zero Nerve, Nerve N,[4] and NT.[5]

| Cranial nerve zero | |

|---|---|

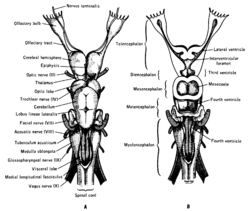

Left The terminal nerve as it is shown on the ventral side of a dog-fish brain. (Topmost label) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nervus terminalis |

| TA | A14.2.01.002 |

| FMA | 76749 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

| Cranial nerves |

|---|

|

Structure

The terminal nerve appears just anterior of the other cranial nerves bilaterally as a microscopic plexus of unmyelinated peripheral nerve fascicles in the subarachnoid space covering the gyrus rectus. This plexus appears near the cribriform plate and travels posteriorly toward the olfactory trigone, medial olfactory gyrus, and lamina terminalis.[2]

The nerve is often overlooked in autopsies because it is unusually thin for a cranial nerve, and is often torn out upon exposing the brain.[4] Careful dissection is necessary to visualize the nerve. Its purpose and mechanism of function is still open to debate; consequently, nerve zero is often not mentioned in anatomy textbooks.[1]

Function

Although very close to[8] (and often confused for a branch of) the olfactory nerve, the terminal nerve is not connected to the olfactory bulb, where smells are analyzed. This fact suggests that the nerve is either vestigial or may be related to the sensing of pheromones. This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that the terminal nerve projects to the medial and lateral septal nuclei and the preoptic areas, all of which are involved in regulating sexual behavior in mammals,[1] as well as a 1987 study finding that mating in hamsters is reduced when the terminal nerve is severed.[9]

Additional images

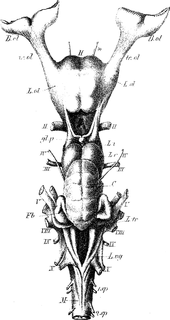

Three forms of the nerve on the underside of human brains.

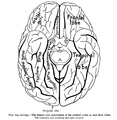

Three forms of the nerve on the underside of human brains. Brain viewed from below. Gyrus rectus seen at anterior centre.

Brain viewed from below. Gyrus rectus seen at anterior centre.

See also

References

- Fields, R. Douglas (2007). "Sex and the Secret Nerve". Scientific American Mind. 18: 20–7. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0207-20.

-

Fuller GN, Burger PC (1990). "Nervus terminalis (cranial nerve zero) in the adult human". Clinical Neuropathology. 9 (6): 279–83. PMID 2286018.

The presence of an additional cranial nerve (the nervus terminalis or cranial nerve zero) is well documented in many non-human vertebrate species. However, its existence in the adult human has been disputed. The present study focused on the structure and incidence of this nerve in the adult human brain. The nerve was examined post-mortem in 10 adult brains using dissection microscopy, light microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and immunohistochemistry. In all specimens, the nervus terminalis was identified bilaterally as a microscopic plexus of unmyelinated peripheral nerve fascicles in the subarachnoid space covering the gyrus rectus of the orbital surface of the frontal lobes. The plexus appeared in the region of the cribriform plate of the ethmoid and coursed posteriorly to the vicinity of the olfactory trigone, medial olfactory gyrus, and lamina terminalis. We conclude that the terminal nerve is a common finding in the adult human brain, confirming early light microscopic reports.

- Berman, Laura (March 25, 2008). "Scientists discover secret sex nerve". TODAY.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- Bordoni, Bruno; Zanier, Emiliano (March 13, 2013). "Cranial nerves XIII and XIV: nerves in the shadows". Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. Dove Medical Press. 6: 87–91. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S39132. eISSN 1178-2390. ISSN 1178-2390. OCLC 319595339. PMC 3601045. PMID 23516138.

- Vilensky, JA (January 2014). "The neglected cranial nerve: nervus terminalis (cranial nerve N)". Clinical Anatomy. 27 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1002/ca.22130. PMID 22836597.

- Whitlock KE (September 2004). "Development of the nervus terminalis: origin and migration". Microscopy Research and Technique. 65 (1–2): 2–12. doi:10.1002/jemt.20094. PMID 15570589.

- Müller F, O'Rahilly R (2004). "Olfactory structures in staged human embryos". Cells Tissues Organs. 178 (2): 93–116. doi:10.1159/000081720. PMID 15604533.

- Von Bartheld CS (September 2004). "The terminal nerve and its relation with extrabulbar "olfactory" projections: lessons from lampreys and lungfishes". Microscopy Research and Technique. 65 (1–2): 13–24. doi:10.1002/jemt.20095. PMID 15570592.

- Wirsig, Celeste (11 August 1987). "Terminal nerve damage impairs the mating behavior of the male hamster". Brain Research. 417 (2): 293–303. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(87)90454-9. PMID 3308003.

External links

- Vilensky JA (January 2014). "The neglected cranial nerve: nervus terminalis (cranial nerve N)". Clinical Anatomy. 27 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1002/ca.22130. PMID 22836597.

- Fuller GN, Burger PC (1990). "Nervus terminalis (cranial nerve zero) in the adult human". Clinical Neuropathology. 9 (6): 279–83. PMID 2286018.