Cataract

A cataract is a clouding of the lens in the eye which leads to a decrease in vision.[1] Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes.[1] Symptoms may include faded colors, blurry or double vision, halos around light, trouble with bright lights, and trouble seeing at night.[1] This may result in trouble driving, reading, or recognizing faces.[7] Poor vision caused by cataracts may also result in an increased risk of falling and depression.[2] Cataracts cause half of all cases of blindness and 33% of visual impairment worldwide.[3][8]

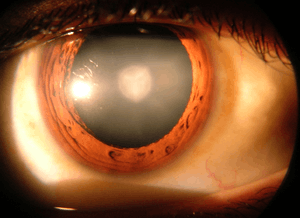

| Cataract | |

|---|---|

| |

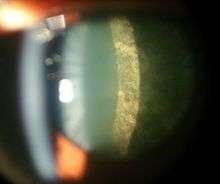

| Magnified view of a cataract seen on examination with a slit lamp | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Faded colors, blurry vision, halos around light, trouble with bright lights, trouble seeing at night[1] |

| Complications | Falling, depression, blindness[2][3] |

| Usual onset | Gradual[1] |

| Causes | Aging, trauma, radiation exposure, following eye surgery, genetic[1][4][5] |

| Risk factors | Diabetes, smoking tobacco, prolonged exposure to sunlight, alcohol[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Eye examination[1] |

| Prevention | Sunglasses, not smoking[1] |

| Treatment | Glasses, cataract surgery[1] |

| Frequency | 60 million (2015)[6] |

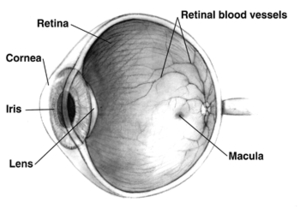

Cataracts are most commonly due to aging but may also occur due to trauma or radiation exposure, be present from birth, or occur following eye surgery for other problems.[1][4] Risk factors include diabetes, smoking tobacco, prolonged exposure to sunlight, and alcohol.[1] The underlying mechanism involves accumulation of clumps of protein or yellow-brown pigment in the lens that reduces transmission of light to the retina at the back of the eye.[1] Diagnosis is by an eye examination.[1]

Prevention includes wearing sunglasses and avoiding smoking.[1] Early on the symptoms may be improved with glasses.[1] If this does not help, surgery to remove the cloudy lens and replace it with an artificial lens is the only effective treatment.[1] Surgery is needed only if the cataracts are causing problems and generally results in an improved quality of life.[1][9] Cataract surgery is not readily available in many countries, which is especially true for women, those living in rural areas, and those who do not know how to read.[4][10]

About 20 million people are blind due to cataracts.[4] It is the cause of approximately 5% of blindness in the United States and nearly 60% of blindness in parts of Africa and South America.[10] Blindness from cataracts occurs in about 10 to 40 per 100,000 children in the developing world, and 1 to 4 per 100,000 children in the developed world.[11] Cataracts become more common with age.[1] In the United States, cataracts occur in 68% of those over the age of 80 years.[12] Additionally they are more common in women and White people.[12]

Signs and symptoms

_PHIL_4284_lores.jpg)

Signs and symptoms vary depending on the type of cataract, though considerable overlap occurs. People with nuclear sclerotic or brunescent cataracts often notice a reduction of vision. Nuclear cataracts typically cause greater impairment of distance vision than of near vision. Those with posterior subcapsular cataracts usually complain of glare as their major symptom.[13]

The severity of cataract formation, assuming no other eye disease is present, is judged primarily by a visual acuity test. Other symptoms include frequent changes of glasses and colored halos due to hydration of lens.

Causes

Age

Age is the most common cause.[1][4] Lens proteins denature and degrade over time, and this process is accelerated by diseases such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Environmental factors, including toxins and radiation, including ultraviolet light, have cumulative effects, which are worsened by the loss of protective and restorative mechanisms due to alterations in gene expression and chemical processes within the eye.[14]

Trauma

Blunt trauma causes swelling, thickening, and whitening of the lens fibers. While the swelling normally resolves with time, the white color may remain. In severe blunt trauma, or in injuries that penetrate the eye, the capsule in which the lens sits can be damaged. This damage allows fluid from other parts of the eye to rapidly enter the lens leading to swelling and then whitening, obstructing light from reaching the retina at the back of the eye. Cataracts may develop in 0.7 to 8.0% of cases following electrical injuries.[15] Blunt trauma can also result in star- (stellate) or petal-shaped cataracts.[16]

Radiation

Cataracts can arise as an effect of exposure to various types of radiation. X-rays, one form of ionizing radiation, may damage the DNA of lens cells.[17] Ultraviolet light, specifically UVB, has also been shown to cause cataracts, and some evidence indicates sunglasses worn at an early age can slow its development in later life.[18] Microwaves, a type of nonionizing radiation, may cause harm by denaturing protective enzymes (e.g., glutathione peroxidase), by oxidizing protein thiol groups (causing protein aggregation), or by damaging lens cells via thermoelastic expansion.[17] The protein coagulation caused by electric and heat injuries whitens the lens.[14] This same process is what makes the clear albumen of an egg become white and opaque during cooking.

Genetics

The genetic component is strong in the development of cataracts,[19] most commonly through mechanisms that protect and maintain the lens. The presence of cataracts in childhood or early life can occasionally be due to a particular syndrome. Examples of chromosome abnormalities associated with cataracts include 1q21.1 deletion syndrome, cri-du-chat syndrome, Down syndrome, Patau's syndrome, trisomy 18 (Edward's syndrome), and Turner's syndrome, and in the case of neurofibromatosis type 2, juvenile cataract on one or both sides may be noted. Examples of single-gene disorder include Alport's syndrome, Conradi's syndrome, cerebrotendineous xanthomatosis, myotonic dystrophy, and oculocerebrorenal syndrome or Lowe syndrome.

Skin diseases

The skin and the lens have the same embryological origin and so can be affected by similar diseases.[20] Those with atopic dermatitis and eczema occasionally develop shield ulcer cataracts. Ichthyosis is an autosomal recessive disorder associated with cuneiform cataracts and nuclear sclerosis. Basal-cell nevus and pemphigus have similar associations.

Smoking and alcohol

Cigarette smoking has been shown to double the rate of nuclear sclerotic cataracts and triple the rate of posterior subcapsular cataracts.[21] Evidence is conflicting over the effect of alcohol. Some surveys have shown a link, but others which followed people over longer terms have not.[22]

Inadequate vitamin C

Low vitamin C intake and serum levels have been associated with greater cataract rates.[23] However, use of supplements of vitamin C has not demonstrated benefit.[24]

Medications

Some medications, such as systemic, topical, or inhaled corticosteroids, may increase the risk of cataract development.[25][26] Corticosteroids most commonly cause posterior subcapsular cataracts.[26] People with schizophrenia often have risk factors for lens opacities (such as diabetes, hypertension, and poor nutrition) but antipsychotic medications are unlikely to contribute to cataract formation.[27] Miotics[28] and triparanol may increase the risk.[29]

Post-operative

Nearly every person who undergoes a vitrectomy—without ever having had cataract surgery—will experience progression of nuclear sclerosis after the operation.[30] This may be because the native vitreous humor is different from the solutions used to replace the vitreous (vitreous substitutes), such as BSS Plus.[31] This may also be because the native vitreous humour contains ascorbic acid which helps neutralize oxidative damage to the lens and because conventional vitreous substitutes do not contain ascorbic acid.[32][33] As such, for phakic patients requiring a vitrectomy it is becoming increasingly common for ophthalmologists to offer the vitrectomy combined with prophylactic cataract surgery to prevent cataract formation.[34]

Other diseases

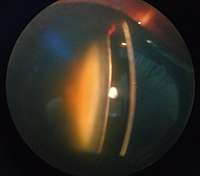

|

|

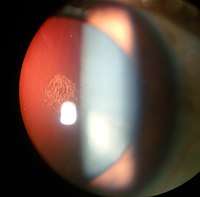

Sunflower cataract of a forty-year-old male with Wilson's disease and decompensated CLD

|

Diagnosis

Classification

Cataracts may be partial or complete, stationary or progressive, or hard or soft. The main types of age-related cataracts are nuclear sclerosis, cortical, and posterior subcapsular.

Nuclear sclerosis is the most common type of cataract, and involves the central or 'nuclear' part of the lens. This eventually becomes hard, or 'sclerotic', due to condensation on the lens nucleus and the deposition of brown pigment within the lens. In its advanced stages it is called a brunescent cataract. In early stages, an increase in sclerosis cause an increase in refractive index of the lens.[35] This causes a myopic shift (lenticular shift) that decreases hyperopia and enables presbyopic patients to see at near without reading glasses. This is only tempororary and is called second sight.

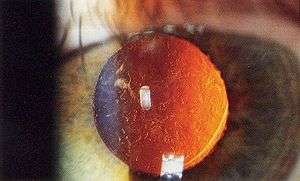

Cortical cataracts are due to the lens cortex (outer layer) becoming opaque. They occur when changes in the fluid contained in the periphery of the lens causes fissuring. When these cataracts are viewed through an ophthalmoscope, or other magnification system, the appearance is similar to white spokes of a wheel. Symptoms often include problems with glare and light scatter at night.[35]

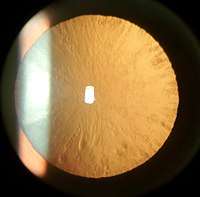

Posterior subcapsular cataracts are cloudy at the back of the lens adjacent to the capsule (or bag) in which the lens sits. Because light becomes more focused toward the back of the lens, they can cause disproportionate symptoms for their size.

An immature cataract has some transparent protein, but with a mature cataract, all the lens protein is opaque. In a hypermature or Morgagnian cataract, the lens proteins have become liquid. Congenital cataract, which may be detected in adulthood, has a different classification and includes lamellar, polar, and sutural cataracts.[36][37]

Cataracts can be classified by using the lens opacities classification system LOCS III. In this system, cataracts are classified based on type as nuclear, cortical, or posterior. The cataracts are further classified based on severity on a scale from 1 to 5. The LOCS III system is highly reproducible.[38]

Posterior polar cataract of an 8 year old boy in left eye

Posterior polar cataract of an 8 year old boy in left eye Nuclear sclerosis cataract of a 70 year old male

Nuclear sclerosis cataract of a 70 year old male Cortical cataract of a 60 year old male

Cortical cataract of a 60 year old male Retroillumination of cortical cataract

Retroillumination of cortical cataract Posterior subcapsular cataract of a 16 year old girl with IDDM

Posterior subcapsular cataract of a 16 year old girl with IDDM Intumescent cataract of a 55 year old male

Intumescent cataract of a 55 year old male Anterior subcapsular cataract having back shadow

Anterior subcapsular cataract having back shadow Posterior subcapsular cataract by retroillumination

Posterior subcapsular cataract by retroillumination Nuclear sclerosis and posterior polar cataract of a 60 year old female

Nuclear sclerosis and posterior polar cataract of a 60 year old female Dense white mature cataract of a 60 year old male

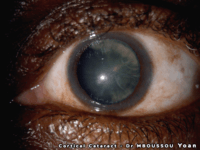

Dense white mature cataract of a 60 year old male Cortical cataract of a melanoderm male

Cortical cataract of a melanoderm male

Prevention

Risk factors such as UVB exposure and smoking can be addressed. Although no means of preventing cataracts has been scientifically proven, wearing sunglasses that counteract ultraviolet light may slow their development.[39][40] While adequate intake of antioxidants (such as vitamins A, C, and E) has been thought to protect against the risk of cataracts, clinical trials have shown no benefit from supplements;[24] though evidence is mixed, but weakly positive, for a potential protective effect of the nutrients lutein and zeaxanthin.[41][42][43] Statin use is somewhat associated with a lower risk of nuclear sclerotic cataracts.[44]

Treatment

Surgical

The appropriateness of surgery depends on a person's particular functional and visual needs and other risk factors.[45] Cataract removal can be performed at any stage and no longer requires ripening of the lens. Surgery is usually 'outpatient' and usually performed using local anesthesia. About 9 of 10 patients can achieve a corrected vision of 20/40 or better after surgery.[35]

Several recent evaluations found that cataract surgery can meet expectations only when significant functional impairment due to cataracts exists before surgery. Visual function estimates such as VF-14 have been found to give more realistic estimates than visual acuity testing alone.[35][46] In some developed countries, a trend to overuse cataract surgery has been noted, which may lead to disappointing results.[47]

Phacoemulsification is the most widely used cataract surgery in the developed world.[48][49] This procedure uses ultrasonic energy to emulsify the cataract lens. Phacoemulsification typically comprises six steps:

- Anaesthetic – The eye is numbed with either a subtenon injection around the eye (see: retrobulbar block) or topical anesthetic eye drops. The former also provides paralysis of the eye muscles.

- Corneal incision – Two cuts are made at the margin of the clear cornea to allow insertion of instruments into the eye.

- Capsulorhexis – A needle or small pair of forceps is used to create a circular hole in the capsule in which the lens sits.

- Phacoemulsification – A handheld ultrasonic probe is used to break up and emulsify the lens into liquid using the energy of ultrasound waves. The resulting 'emulsion' is sucked away.

- Irrigation and aspiration – The cortex, which is the soft outer layer of the cataract, is aspirated or sucked away. Fluid removed is continually replaced with a saline solution to prevent collapse of the structure of the anterior chamber (the front part of the eye).

- Lens insertion – A plastic, foldable lens is inserted into the capsular bag that formerly contained the natural lens. Some surgeons also inject an antibiotic into the eye to reduce the risk of infection. The final step is to inject salt water into the corneal wounds to cause the area to swell and seal the incision.

A Cochrane review found little to no difference in visual acuity as a function of the size of incisions made for phacoemulsification in the range from <= 1.5 mm to 3.0 mm.[50]

Extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) consists of removing the lens manually, but leaving the majority of the capsule intact.[51] The lens is expressed through a 10- to 12-mm incision which is closed with sutures at the end of surgery. ECCE is less frequently performed than phacoemulsification, but can be useful when dealing with very hard cataracts or other situations where emulsification is problematic. Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS) has evolved from ECCE. In MSICS, the lens is removed through a self-sealing scleral tunnel wound in the sclera which, ideally, is watertight and does not require suturing. Although "small", the incision is still markedly larger than the portal in phacoemulsion. This surgery is increasingly popular in the developing world where access to phacoemulsification is still limited.

Intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE) is rarely performed.[52] The lens and surrounding capsule are removed in one piece through a large incision while pressure is applied to the vitreous membrane. The surgery has a high rate of complications.

Prognosis

Postoperative care

.jpg)

The postoperative recovery period (after removing the cataract) is usually short. The patient is usually ambulatory on the day of surgery, but is advised to move cautiously and avoid straining or heavy lifting for about a month. The eye is usually patched on the day of surgery and use of an eye shield at night is often suggested for several days after surgery.[45]

In all types of surgery, the cataractous lens is removed and replaced with an artificial lens, known as an intraocular lens, which stays in the eye permanently. Intraocular lenses are usually monofocal, correcting for either distance or near vision. Multifocal lenses may be implanted to improve near and distance vision simultaneously, but these lenses may increase the chance of unsatisfactory vision.[14]

Complications

Serious complications of cataract surgery include retinal detachment and endophthalmitis.[53] In both cases, patients notice a sudden decrease in vision. In endophthalmitis, patients often describe pain. Retinal detachment frequently presents with unilateral visual field defects, blurring of vision, flashes of light, or floating spots.

The risk of retinal detachment was estimated as about 0.4% within 5.5 years, corresponding to a 2.3-fold risk increase compared to naturally expected incidence, with older studies reporting a substantially higher risk. The incidence is increasing over time in a somewhat linear manner, and the risk increase lasts for at least 20 years after the procedure. Particular risk factors are younger age, male sex, longer axial length, and complications during surgery. In the highest risk group of patients, the incidence of pseudophakic retinal detachment may be as high as 20%.[54][55]

The risk of endophthalmitis occurring after surgery is less than one in 1000.[56]

Corneal edema and cystoid macular edema are less serious but more common, and occur because of persistent swelling at the front of the eye in corneal edema or back of the eye in cystoid macular edema.[57] They are normally the result of excessive inflammation following surgery, and in both cases, patients may notice blurred, foggy vision. They normally improve with time and with application of anti-inflammatory drops. The risk of either occurring is around one in 100. It is unclear whether NSAIDs or corticosteroids are superior at reducing postoperative inflammation.[58]

Posterior capsular opacification, also known as after-cataract, is a condition in which months or years after successful cataract surgery, vision deteriorates or problems with glare and light scattering recur, usually due to thickening of the back or posterior capsule surrounding the implanted lens, so-called 'posterior lens capsule opacification'. Growth of natural lens cells remaining after the natural lens was removed may be the cause, and the younger the patient, the greater the chance of this occurring. Management involves cutting a small, circular area in the posterior capsule with targeted beams of energy from a laser, called Nd:YAG laser capsulotomy, after the type of laser used. The laser can be aimed very accurately, and the small part of the capsule which is cut falls harmlessly to the bottom of the inside of the eye. This procedure leaves sufficient capsule to hold the lens in place, but removes enough to allow light to pass directly through to the retina. Serious side effects are rare.[59] Posterior capsular opacification is common and occurs following up to one in four operations, but these rates are decreasing following the introduction of modern intraocular lenses together with a better understanding of the causes.

Vitreous touch syndrome is a possible complication of intracapsular cataract extraction.[60]

Epidemiology

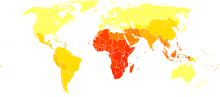

|

no data

<90

90–180

180–270

270–360

360–450

450–540

|

540–630

630–720

720–810

810–900

900–990

>990

|

Age-related cataracts are responsible for 51% of world blindness, about 20 million people.[62] Globally, cataracts cause moderate to severe disability in 53.8 million (2004), 52.2 million of whom are in low and middle income countries.[63]

In many countries, surgical services are inadequate, and cataracts remain the leading cause of blindness.[62] Even where surgical services are available, low vision associated with cataracts may still be prevalent as a result of long waits for, and barriers to, surgery, such as cost, lack of information and transportation problems.

In the United States, age-related lens changes have been reported in 42% between the ages of 52 and 64,[64] 60% between the ages 65 and 74,[65] and 91% between the ages of 75 and 85.[64] Cataracts affect nearly 22 million Americans age 40 and older. By age 80, more than half of all Americans have cataracts. Direct medical costs for cataract treatment are estimated at $6.8 billion annually.[66]

In the eastern Mediterranean region, cataracts are responsible for over 51% of blindness. Access to eye care in many countries in this region is limited.[67] Childhood-related cataracts are responsible for 5–20% of world childhood blindness.[68]

History

Cataract surgery was first described by the Indian physician, Suśruta (about 5th century BCE) in his manuscript Sushruta Samhita in ancient India. Most of the methods mentioned focus on hygiene. Follow-up treatments include bandaging of the eye and covering the eye with warm butter.[69] References to cataracts and their treatment in Ancient Rome are also found in 29 AD in De Medicinae, the work of the Latin encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus.[70] Archaeological evidence of eye surgery in the Roman era also exists.[71]

Galen of Pergamon (ca. 2nd century CE), a prominent Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher, performed an operation similar to modern cataract surgery. Using a needle-shaped instrument, Galen attempted to remove the cataract-affected lens of the eye.[72]

Muslim ophthalmologist Ammar Al-Mawsili, in his Choice of Eye Diseases, written circa 1000, wrote of his invention of a syringe and the technique of cataract extraction while experimenting with it on a patient.[73]

Etymology

"Cataract" is derived from the Latin cataracta, meaning "waterfall", and from the Ancient Greek καταρράκτης (katarrhaktēs), "down-rushing",[74] from καταράσσω (katarassō) meaning "to dash down"[75] (from kata-, "down"; arassein, "to strike, dash").[76] As rapidly running water turns white, so the term may have been used metaphorically to describe the similar appearance of mature ocular opacities. In Latin, cataracta had the alternative meaning "portcullis"[77] and the name possibly passed through French to form the English meaning "eye disease" (early 15th century), on the notion of "obstruction".[78] Early Persian physicians called the term nazul-i-ah, or "descent of the water"—vulgarised into waterfall disease or cataract—believing such blindness to be caused by an outpouring of corrupt humour into the eye.[79]

Research

N-Acetylcarnosine drops have been investigated as a medical treatment for cataracts. The drops are believed to work by reducing oxidation and glycation damage in the lens, particularly reducing crystallin crosslinking.[80][81] Some benefit has been shown in small manufacturer-sponsored randomized controlled trials but further independent corroboration is still required.[82]

Femtosecond laser mode-locking, used during cataract surgery, was originally used to cut accurate and predictable flaps in LASIK surgery, and has been introduced to cataract surgery. The incision at the junction of the sclera and cornea and the hole in capsule during capsulorhexis, traditionally made with a handheld blade, needle, and forceps, are dependent on skill and experience of the surgeon. Sophisticated three-dimensional images of the eyes can be used to guide lasers to make these incisions. Nd:YAG laser can also then break up the cataract as in phacoemulsification.[83]

Stem cells have been used in a clinical trial for lens regeneration in twelve children under the age of two with cataracts present at birth.[84] The children were followed for six months, so it is unknown what the long-term results will be, and it is unknown if this procedure would work in adults.[84]

See also

- Galactosemic cataract

- Intraocular lens

References

- "Facts About Cataract". September 2009. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Gimbel, HV; Dardzhikova, AA (January 2011). "Consequences of waiting for cataract surgery". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 22 (1): 28–30. doi:10.1097/icu.0b013e328341425d. PMID 21076306.

- "Visual impairment and blindness Fact Sheet N°282". August 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- "Priority eye diseases". Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Chan, WH; Biswas, S; Ashworth, JL; Lloyd, IC (April 2012). "Congenital and infantile cataract: aetiology and management". European Journal of Pediatrics. 171 (4): 625–30. doi:10.1007/s00431-012-1700-1. PMID 22383071.

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- Allen D, Vasavada A (2006). "Cataract and surgery for cataract". BMJ. 333 (7559): 128–32. doi:10.1136/bmj.333.7559.128. PMC 1502210. PMID 16840470.

- GLOBAL DATA ON VISUAL IMPAIRMENTS 2010 (PDF). WHO. 2012. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-03-31.

- Lamoureux, EL; Fenwick, E; Pesudovs, K; Tan, D (January 2011). "The impact of cataract surgery on quality of life". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 22 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1097/icu.0b013e3283414284. PMID 21088580.

- Rao, GN; Khanna, R; Payal, A (January 2011). "The global burden of cataract". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 22 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1097/icu.0b013e3283414fc8. PMID 21107260.

- Pandey, Suresh K. (2005). Pediatric cataract surgery techniques, complications, and management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 20. ISBN 9780781743075. Archived from the original on 2015-05-24.

- "Cataract Data and Statistics | National Eye Institute". www.nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- "Posterior Supcapsular Cataract". Digital Reference of Ophthalmology. Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology of Columbia University. 2003. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Duker, Jay S.; Myron Yanoff MD; Yanoff, Myron; Jay S. Duker MD (2009). Ophthalmology. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-04332-8.

- Reddy SC (1999). "Electric cataract: a case report and review of the literature". European Journal of Ophthalmology. 9 (2): 134–8. doi:10.1177/112067219900900211. PMID 10435427.

- Ram, Jagat; Gupta, Rohit (2016). "Petaloid Cataract". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (18): e22. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1507349. PMID 27144871.

- Lipman RM, Tripathi BJ, Tripathi RC (1988). "Cataracts induced by microwave and ionizing radiation". Surv. Ophthalmol. 33 (3): 200–10. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(88)90088-4. PMID 3068822.

- Sliney DH (1994). "UV radiation ocular exposure dosimetry". Doc. Ophthalmol. 88 (3–4): 243–54. doi:10.1007/bf01203678. PMID 7634993.

- Hejtmancik; Smaoui (2003), "Molecular Genetics of Cataract", Genetics in Ophthalmology, Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers, p. 77, ISBN 9783805575782

- Yanoff, Myron; Duker, Jay (2009), Ophthalmology, Elsevier Health Sciences, p. 507, ISBN 9780323043328

- Christen WG, Manson JE, Seddon JM, Glynn RJ, Buring JE, Rosner B, Hennekens CH (August 1992). "A prospective study of cigarette smoking and risk of cataract in men". JAMA. 268 (8): 989–93. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03490080063025. PMID 1501324.

- Wang S, Wang JJ, Wong TY (2008). "Alcohol and eye diseases". Surv. Ophthalmol. 53 (5): 512–25. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.06.003. PMID 18929762.

- Wei, L.; Liang, G.; Cai, C.; Lv, J. (May 2016). "Association of vitamin C with the risk of age-related cataract: a meta-analysis". Acta Ophthalmologica. 94 (3): e170–6. doi:10.1111/aos.12688. PMID 25735187.

- Mathew MC, Ervin AM, Tao J, Davis RM (Jun 13, 2012). "Antioxidant vitamin supplementation for preventing and slowing the progression of age-related cataract". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD004567. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004567.pub2. PMC 4410744. PMID 22696344.

- Weatherall, M; Clay, J; James, K; Perrin, K; Shirtcliffe, P; Beasley, R (September 2009). "Dose-response relationship of inhaled corticosteroids and cataracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Respirology (Carlton, Vic.). 14 (7): 983–90. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01589.x. PMID 19740259.

- Hodge, WG; Whitcher, JP; Satariano, W (1995). "Risk factors for age-related cataracts". Epidemiologic Reviews. 17 (2): 336–46. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036197. PMID 8654515.

- Uçok A, Gaebel W (February 2008). "Side effects of atypical antipsychotics: a brief overview". World Psychiatry. 7 (1): 58–62. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00154.x. PMC 2327229. PMID 18458771.

- van den Brûle J, Degueldre F, Galand A (December 1998). "Cataractes incitées de médicament" [Drug-induced cataracts]. Revue Médicale de Liège (in French). 53 (12): 766–9. PMID 9927876.

- "Triperanol". MeSH. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- Almony, Arghavan; Holekamp, Nancy M; Bai, Fang; Shui, Ying-Bo; Beebe, David (2012). "Small-gauge vitrectomy does not protect against nuclear sclerotic cataract". Retina. 32 (3): 499–505. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e31822529cf. PMID 22392091.

- Kokavec, Jan; Min, San H; Tan, Mei H; Gilhotra, Jagjit S; Newland, Henry S; Durkin, Shane R; Grigg, John; Casson, Robert J (2016). "Biochemical analysis of the living human vitreous". Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 44 (7): 597–609. doi:10.1111/ceo.12732. PMID 26891415.

- Donati, Simone; Caprani, Simona Maria; Airaghi, Giulia; Vinciguerra, Riccardo; Bartalena, Luigi; Testa, Francesco; Mariotti, Cesare; Porta, Giovanni; Simonelli, Francesca; Azzolini, Claudio (2014). "Vitreous Substitutes: The Present and the Future". BioMed Research International. 2014: 1–12. doi:10.1155/2014/351804. PMC 4024399. PMID 24877085.

- Shui, Ying-Bo; Holekamp, Nancy M.; Kramer, Benjamin C.; Crowley, Jan R.; Wilkins, Mark A.; Chu, Fred; Malone, Paula E.; Mangers, Shayna J.; Hou, Joshua H.; Siegfried, Carla J.; Beebe, David C. (2009). "The Gel State of the Vitreous and Ascorbate-Dependent Oxygen Consumption". Archives of Ophthalmology. 127 (4): 475–82. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.621. PMC 2683478. PMID 19365028.

- Jalil, A; Steeples, L; Subramani, S; Bindra, M S; Dhawahir-Scala, F; Patton, N (2014). "Microincision cataract surgery combined with vitrectomy: a case series". Eye. 28 (4): 386–9. doi:10.1038/eye.2013.300. PMC 3983625. PMID 24406418.

- Bollinger KE, Langston RH (2008). "What can patients expect from cataract surgery?" (PDF). Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 75 (3): 193–196, 199–196. doi:10.3949/ccjm.75.3.193. PMID 18383928.

- Spencer RW, Andelman SY (1965). "Steroid cataracts. Posterior subcapsular cataract formation in rheumatoid arthritis patients on long term steroid therapy". Arch. Ophthalmol. 74: 38–41. doi:10.1001/archopht.1965.00970040040009. PMID 14303339.

- Greiner JV, Chylack LT (1979). "Posterior subcapsular cataracts: histopathologic study of steroid-associated cataracts". Arch. Ophthalmol. 97 (1): 135–44. doi:10.1001/archopht.1979.01020010069017. PMID 758890.

- Yanoff, Myron; Duker, Jay S. (2008). Ophthalmology (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Mosby. p. 412. ISBN 978-0323057516.

- Neale RE, Purdie JL, Hirst LW, Green AC (November 2003). "Sun exposure as a risk factor for nuclear cataract". Epidemiology. 14 (6): 707–712. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000086881.84657.98. PMID 14569187.

- Javitt JC, Wang F, West SK (1996). "Blindness Due to Cataract: Epidemiology and Prevention" (PDF). Annual Review of Public Health. 17: 159–77. doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.001111. PMID 8724222. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 6, 2008. Cited in Five-Year Agenda for the National Eye Health Education Program (NEHEP), p. B-2; National Eye Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health

- Barker FM (August 2010). "Dietary supplementation: effects on visual performance and occurrence of AMD and cataracts". Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 26 (8): 2011–23. doi:10.1185/03007995.2010.494549. PMID 20590393.

- Ma, L.; Hao, Z.; Liu, R.; Yu, R.; Shi, Q.; Pan, J. (2013). "A dose–response meta-analysis of dietary lutein and zeaxanthin intake in relation to risk of age-related cataract". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 252 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1007/s00417-013-2492-3. PMID 24150707.

- Hayashi, R. (2014-11-01). "The Effects of Lutein in Preventing Cataract Progression". In Babizhayev, M. A.; Li, D. W.-C.; Kasus-Jacobi, A.; Žorić, L.; Alió, J. L. (eds.). Studies on the Cornea and Lens. Oxidative Stress in Applied Basic Research and Clinical Practice. pp. 317–326. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-1935-2_17. ISBN 9781493919345.CS1 maint: uses editors parameter (link)

- Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE, Grady LM (2006). "Statin Use and Incident Nuclear Cataract". Journal of the American Medical Association. 295 (23): 2752–8. doi:10.1001/jama.295.23.2752. PMID 16788130.

- Emmett T. Cunningham; Paul Riordan-Eva (2011-05-17). Vaughan & Asbury's general ophthalmology (18th ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0071634205.

- Davis JC, McNeill H, Wasdell M, Chunick S, Bryan S (2012). "Focussing both eyes on health outcomes: Revisiting cataract surgery". BMC Geriatrics. 12: 50. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-12-50. PMC 3497611. PMID 22943071.

- Black N, Browne J, van der Meulen J, Jamieson L, Copley L, Lewsey J (2008). "Is there overutilisation of cataract surgery in England?" (PDF). British Journal of Ophthalmology. 93 (1): 13–17. doi:10.1136/bjo.2007.136150. PMID 19098042.

- Eunbi Kim; Sam Young Yoon; Young Joo Shin (2014), Studies on the Cornea and Lens, Springer, p. 4, ISBN 9781493919352

- Hasler, Pascal (2013), Essential Principles of Phacoemulsification, JP Medical Ltd, ISBN 9789962678618

- Jin C, Chen X, Law A, Kang Y, Wang X, Xu W, Yao K (2017). "Different-sized incisions for phacoemulsification in age-related cataract". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9: CD010510. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010510.pub2. PMC 5665700. PMID 28931202.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Henderson, Bonnie (2007), "Extracapsular Cataract Extraction", Essentials of Cataract Surgery, SLACK, p. 187, ISBN 9781556428029

- Goes, Frank (2013), The Eye in History, JP Medical, p. 367, ISBN 9789350902745

- Naumann; Holbach; Kruse, eds. (2008), "Complications After Cataract Surgery", Applied Pathology for Ophthalmic Microsurgeons, Springer Science & Business, p. 247, ISBN 9783540683667

- Olsen T, Jeppesen P (2012). "The Incidence of Retinal Detachment After Cataract Surgery". The Open Ophthalmology Journal. 6: 79–82. doi:10.2174/1874364101206010079. PMC 3447164. PMID 23002414.

- Herrmann W, Helbig H, Heimann H (2011). "Pseudophakie-Ablatio". Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde. 228 (3): 195–200. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1246116. PMID 21374539.

- Behndig A, Montan P, Stenevi U, Kugelberg M, Lundström M (August 2011). "One million cataract surgeries: Swedish National Cataract Register 1992–2009". J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 37 (8): 1539–45. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.05.021. PMID 21782099.

- Gault, Janice; Vander, James (2015), Ophthalmology Secrets in Color, Elsevier Health Sciences, p. 221, ISBN 9780323378024

- Juthani VV, Clearfield E, Chuck RS (2017). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus corticosteroids for controlling inflammation after uncomplicated cataract surgery". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7: CD010516. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010516.pub2. PMC 5580934. PMID 28670710.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Posterior capsule opacification – why laser treatment is sometimes needed following cataract surgery". rnib.org.uk. 2014-02-19. Archived from the original on 2009-09-17.

- Dr. Kushal Banerjee (2006). "A review and clinical evaluation of per-operative and post-operative complications in case of manual small incision cataract surgery and extracapsular cataract extraction with posterior chamber intra-ocular lens implantation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- "Death and DALY estimates for 2004 by cause for WHO Member States" (xls). World Health Organization. who.int. 2004.

- "Priority eye diseases: Cataract". Prevention of Blindness and Visual Impairment. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2015-05-24.

- The global burden of disease : 2004 update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2008. p. 35. ISBN 9789241563710.

- Sperduto RD, Seigel D (Jul 1980). "Senile lens and senile macular changes in a population-based sample". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 90 (1): 86–91. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75081-0. PMID 7395962.

- Kahn HA, Leibowitz HM, Ganley JP, Kini MM, Colton T, Nickerson RS, Dawber TR (Jul 1977). "The Framingham Eye Study. I. Outline and major prevalence findings". Am. J. Epidemiol. 106 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112428. PMID 879158.

- "Eye Health Statistics at a Glance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 17, 2015.

- "Health Topics: Cataract". World Health Organization – Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office. Archived from the original on 2013-09-27.

- Liu, Yu-Chi; Wilkins, Mark; Kim, Terry; Malyugin, Boris; Mehta, Jodhbir S (2017). "Cataracts". The Lancet. 390 (10094): 600–612. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30544-5. PMID 28242111.

- Goes, Frank Joseph (2013). The Eye in History. JP Medical Ltd. p. 371. ISBN 9789350902745.

- Aulus Cornelius Celsus, G. F. Collier (transl.) (1831). De Medicinae. OL 5225311W.

- Elliott, Jane (February 9, 2008). "The Romans carried out cataract ops". BBC News. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008.

- Keele, K. D. (1963). "Galen: On Anatomical Procedures: the Later Books". Med Hist. 7 (1): 85–87. doi:10.1017/s002572730002799x. PMC 1034789.

- Finger, Stanley (1994). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3.

- καταρράκτης Archived 2012-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- καταράσσω Archived 2012-04-04 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott,A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- "cataract". Word of the Day. Dictionary.com. 29 October 2003. Archived from the original on 23 December 2005.

"cataract". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. - cataracta Archived 2012-04-04 at the Wayback Machine, Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, on Perseus

- Online Etymology Dictionary Archived 2007-10-14 at the Wayback Machine, etymonline.com

- Mistaken Science — Topic Powered by eve community Archived 2008-06-22 at the Wayback Machine, Wordcraft Forums, wordcraft.infopop.cc

- Williams DL, Munday P (2006). "The effect of a topical antioxidant formulation including N-acetyl carnosine on canine cataract: a preliminary study". Vet Ophthalmol. 9 (5): 311–6. doi:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2006.00492.x. PMID 16939459.

- Guo Y, Yan H (2006). "Preventive effect of carnosine on cataract development". Yan Ke Xue Bao. 22 (2): 85–8. PMID 17162883.

- Toh T, Morton J, Coxon J, Elder MJ (2007). "Medical treatment of cataract". Clin. Experiment. Ophthalmol. 35 (7): 664–71. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2007.01559.x. PMID 17894689.

- Friedman NJ, Palanker DV, Schuele G, Andersen D, Marcellino G, Seibel BS, Batlle J, Feliz R, Talamo JH, Blumenkranz MS, Culbertson WW (July 2011). "Femtosecond laser capsulotomy". J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 37 (7): 1189–98. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.04.022. PMID 21700099. as PDF Archived 2012-09-14 at the Wayback Machine The authors declare a financial interest in a company producing femtosecond laser equipment.

- "Stem cells used to repair children's eyes after cataracts". NHS. March 10, 2016. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |