Floater

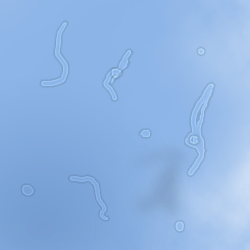

Floaters are sometimes visible deposits within the eye's vitreous humour ("the vitreous"), which is normally transparent.[2][3] Each floater can be measured by its size, shape, consistency, refractive index, and motility. [2] They are also called muscae volitantes (Latin for 'flying flies'), or mouches volantes (from the French).[4] The vitreous usually starts out transparent, but imperfections may gradually develop as one ages. The common type of floater, present in most persons' eyes, is due to these degenerative changes of the vitreous. The perception of floaters, which may be annoying or problematic to some people, is known as myodesopsia,[5] or, less commonly, as myodaeopsia, myiodeopsia, or myiodesopsia. It is not often treated, except in severe cases, where vitrectomy (surgery), laser vitreolysis, and medication may have efficacy.

| Floater | |

|---|---|

| |

| Simulated image of separated, unclumped floaters against a blue sky | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| Differential diagnosis | Migraine aura[1] |

Floaters are visible either because of the shadows they cast on the retina,[6] or because of the refraction of light that passes through them, and can appear alone or together with several others as a clump in one's visual field. They may appear as spots, threads, or fragments of "cobwebs", which float slowly before the observer's eyes, and move especially in the direction the eyes move.[3] As these objects exist within the eye itself, they are not optical illusions but are entoptic phenomena (caused by the eye itself). They are not to be confused with visual snow, which is similar to the static on a television screen, although these two conditions may co-exist as part of a number of visual disturbances which include starbursts, trails, and afterimages.

Signs and symptoms

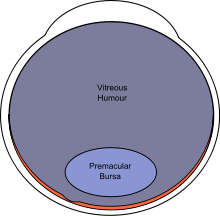

| |

Eye floaters are suspended in the vitreous humour, the thick fluid or gel that fills the eye.[7] The vitreous humour, or vitreous body, is a jelly-like, transparent substance that fills the majority of the eye. It lies within the vitreous chamber behind the lens, and is one of the four optical components of the eye.[8] Thus, floaters follow the rapid motions of the eye, while drifting slowly within the fluid. When they are first noticed, the natural reaction is to attempt to look directly at them. However, attempting to shift one's gaze toward them can be difficult as floaters follow the motion of the eye, remaining to the side of the direction of gaze. Floaters are, in fact, visible only because they do not remain perfectly fixed within the eye. Although the blood vessels of the eye also obstruct light, they are invisible under normal circumstances because they are fixed in location relative to the retina, and the brain "tunes out" stabilized images through neural adaptation. This stabilization is often interrupted by floaters, especially when they tend to remain visible.[3]

Floaters are particularly noticeable when looking at a blank surface or an open monochromatic space, such as blue sky. Despite the name "floaters", many of these specks have a tendency to sink toward the bottom of the eyeball, in whichever way the eyeball is oriented; the supine position (looking up or lying back) tends to concentrate them near the fovea, which is the center of gaze, while the textureless and evenly lit sky forms an ideal background against which to view them.[7] The brightness of the daytime sky also causes the eyes' pupils to contract, reducing the aperture, which makes floaters less blurry and easier to see.

Floaters present at birth usually remain lifelong, while those that appear later may disappear within weeks or months.[9] They are not uncommon, and do not cause serious problems for most persons; they represent one of the most common presentations to hospital eye services. A survey of optometrists in 2002 suggested that an average of 14 patients per month per optometrist presented with symptoms of floaters in the UK.[10] However, floaters are more than a nuisance and a distraction to those with severe cases, especially if the spots seem constantly to drift through the field of vision. The shapes are shadows projected onto the retina by tiny structures of protein or other cell debris discarded over the years and trapped in the vitreous humour. Floaters can even be seen when the eyes are closed on especially bright days, when sufficient light penetrates the eyelids to cast the shadows. It is not, however, only elderly persons who are troubled by floaters; they can also become a problem to younger people, especially if they are myopic. They are also common after cataract operations or after trauma.

Floaters are able to catch and refract light in ways that somewhat blur vision temporarily until the floater moves to a different area. Often they trick persons who are troubled by floaters into thinking they see something out of the corner of their eye that really is not there. Most persons come to terms with the problem, after a time, and learn to ignore their floaters. For persons with severe floaters it is nearly impossible to ignore completely the large masses that constantly stay within almost direct view.

Causes

There are various causes for the appearance of floaters, of which the most common are described here.

Floaters can occur when eyes age; in rare cases, floaters may be a sign of retinal detachment or a retinal tear.[11]

Vitreous syneresis

The most common cause of floaters is shrinkage of the vitreous humour. This gel-like substance consists of 99% water and 1% solid elements. The solid portion consists of a network of collagen and hyaluronic acid, with the latter retaining water molecules. Depolymerization of this network makes the hyaluronic acid release its trapped water, thereby liquefying the gel. The collagen breaks down into fibrils, which ultimately are the floaters that plague the patient.

Vitreous detachments and retinal detachments

In time, the liquefied vitreous body loses support and its framework contracts. This leads to posterior vitreous detachment, in which the vitreous membrane is released from the sensory retina. During this detachment, the shrinking vitreous can stimulate the retina mechanically, causing the patient to see random flashes across the visual field, sometimes referred to as "flashers", a symptom more formally referred to as photopsia. The ultimate release of the vitreous around the optic nerve head sometimes makes a large floater appear, usually in the shape of a ring ("Weiss ring").[12] As a complication, part of the retina might be torn off by the departing vitreous membrane, in a process known as retinal detachment. This will often leak blood into the vitreous, which is seen by the patient as a sudden appearance of numerous small dots, moving across the whole field of vision. Retinal detachment requires immediate medical attention, as it can easily cause blindness. Consequently, both the appearance of flashes and the sudden onset of numerous small floaters should be rapidly investigated by an eye care provider.[13]

Posterior vitreous detachment is more common in people who:

- are nearsighted;

- have undergone cataract surgery;

- have had Nd:YAG laser surgery of the eye;

- have had inflammation inside the eye.[14]

Regression of the hyaloid artery

The hyaloid artery, an artery running through the vitreous humour during the fetal stage of development, regresses in the third trimester of pregnancy. Its disintegration can sometimes leave cell matter.[15]

Other common causes

Patients with retinal tears may experience floaters if red blood cells are released from leaky blood vessels, and those with uveitis or vitritis, as in toxoplasmosis, may experience multiple floaters and decreased vision due to the accumulation of white blood cells in the vitreous humour.[16]

Other causes for floaters include cystoid macular edema and asteroid hyalosis. The latter is an anomaly of the vitreous humour, whereby calcium clumps attach themselves to the collagen network. The bodies that are formed in this way move slightly with eye movement, but then return to their fixed position.

Diagnosis

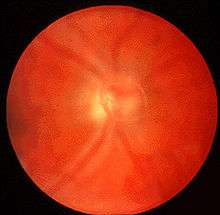

Floaters are often readily observed by an ophthalmologist or an optometrist with the use of an ophthalmoscope or slit lamp. However, if the floater is near the retina, it may not be visible to the observer even if it appears large to the patient.

Increasing background illumination or using a pinhole to effectively decrease pupil diameter may allow a person to obtain a better view of his or her own floaters. The head may be tilted in such a way that one of the floaters drifts towards the central axis of the eye. In the sharpened image the fibrous elements are more conspicuous.[17]

The presence of retinal tears with new onset of floaters was surprisingly high (14%; 95% confidence interval, 12–16%) as reported in a meta-analysis published as part of the Rational Clinical Examination Series in the Journal of the American Medical Association.[18] Patients with new onset flashes and/or floaters, especially when associated with visual loss or restriction in the visual field, should seek more urgent ophthalmologic evaluation.

Treatment

While surgeries do exist to correct for severe cases of floaters, there are no medications (including eye drops) that can correct for this vitreous deterioration. Floaters are often caused by the normal aging process and will usually disappear as the brain learns to ignore them. Looking up/down and left/right will cause the floaters to leave the direct field of vision as the vitreous humour swirls around due to the sudden movement.[19] If floaters significantly increase in numbers and/or severely affect vision, then one of the below treatments may be necessary.

As of 2017, insufficient evidence is available to compare the safety and efficacy of surgical vitrectomy with laser vitreolysis for the treatment of floaters. A 2017 Cochrane Review did not find any relevant studies that compared the two treatments.[20]

Aggressive marketing campaigns have promoted the use of laser vitreolysis for the treatment of floaters.[21][22] No strong evidence currently exists for the treatment of floaters with laser vitreolysis. The strongest available evidence comparing these two treatment modalities are retrospective case series.[23]

Surgery

Vitrectomy may be successful in treating more severe cases.[24][25] The technique usually involves making three openings through the part of the sclera known as the pars plana. Of these small gauge instruments, one is an infusion port to resupply a saline solution and maintain the pressure of the eye, the second is a fiber optic light source, and the third is a vitrector. The vitrector has a reciprocating cutting tip attached to a suction device. This design reduces traction on the retina via the vitreous material. A variant sutureless, self-sealing technique is sometimes used.

Like most invasive surgical procedures, however, vitrectomy carries a risk of complications,[26] including: retinal detachment, anterior vitreous detachment and macular edema – which can threaten vision or worsen existing floaters (in the case of retinal detachment).

Laser

Laser vitreolysis is a possible treatment option for the removal of vitreous strands and opacities (floaters). In this procedure an ophthalmic laser (usually a yttrium aluminium garnet (YAG) laser) applies a series of nanosecond pulses of low-energy laser light to evaporate the vitreous opacities and to sever the vitreous strands. When performed with a YAG laser designed specifically for vitreolysis, reported side effects and complications associated with vitreolysis are rare. However, YAG lasers have traditionally been designed for use in the anterior portion of the eye, i.e. posterior capsulotomy and iridotomy treatments. As a result, they often provide a limited view of the vitreous, which can make it difficult to identify the targeted floaters and membranes. They also carry a high risk of damage to surrounding ocular tissue. Accordingly, vitreolysis is not widely practised, being performed by very few specialists. One of them, John Karickhoff, has performed the procedure more than 1,400 times and claims a 90 percent success rate.[27] However, the MedicineNet web site states that "there is no evidence that this [laser treatment] is effective. The use of a laser also poses significant risks to the vision in what is otherwise a healthy eye."[28]

Medication

Enzymatic vitreolysis has been trialled to treat vitreomacular traction (VMT) and anomalous posterior vitreous detachment. Whilst the mechanism of action may have an effect on clinically significant floaters, as of March 2015 there are no clinical trials being undertaken to determine whether this may be a therapeutic alternative to either conservative management, or vitrectomy.[29]

See also

- Blue field entoptic phenomenon, alias Scheerer's phenomenon – tiny bright dots moving quickly in the visual field.

- Distorted vision

- Phosphene

- Synchysis scintillans

- Scotoma

- Ocular straylight

References

- Johnson, D.; Hollands, H. (2011-11-28). "Acute-onset floaters and flashes". Canadian Medical Association Journal. Joule Inc. 184 (4): 431. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110686. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 3291672.

- Cline D; Hofstetter HW; Griffin JR. Dictionary of Visual Science. 4th ed. Butterworth-Heinemann, Boston 1997. ISBN 0-7506-9895-0

- "Facts About Floaters". National Eye Institute. October 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- Adult Eye Health: Mayo Clinic Radio (5 minutes in to 8 minute talk)

- From Greek μυιώδης "fly-like" (Myiodes was also the name of a fly-deterring deity) and ὄψις "sight."

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. "Floaters and Flashes: A Closer Look" (pamphlet) San Francisco: AAO, 2006. ISBN 1-56055-371-5

- "Eye floaters and spots; Floaters or spots in the eye". National Eye Institute. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- Saladin, Kenneth (2012). Anatomy & Physiology: A Unity of Form and Function. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 614. ISBN 978-0-07-337825-1.

- "Floaters may remain indefinitely". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- Craig Goldsmith; Tristan McMullan; Ted Burton (2007). "Floaterectomy Versus Conventional Pars Plana Vitrectomy For Vitreous Floaters". Digital Journal of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 2008-04-11. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Floaters". NHS choices. NHS GOV.UK. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- "Flashes & Floaters". The Eye Digest. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- "Flashes and Floaters (Posterior Vitreous Detachment)". St. Luke's Cataract & Laser Institute. Archived from the original on 2010-05-02. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology – patient education pamphlet

- Floaters in fetal development Archived December 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Alan G. Kabat; Joseph W. Sowka (April 2009). "A clinician's guide to flashes and floaters" (PDF). optometry.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- Judith Lee, and Gretchyn Bailey;; Dr. Vance Thompson. "Eye floaters and spots". All about vision. Retrieved 2008-02-01.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hollands H, Johnson D, Brox AC, Almeida D, Simel DL, Sharma S. Acute-onset floaters and flashes: is this patient at risk for retinal detachment? JAMA. 2009 November 25;302(20):2243–9.

- "Flashes and Floaters" (PDF). National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Kokavec J, Wu Z, Sherwin JC, Ang AJ, Ang GS (2017). "Nd:YAG laser vitreolysis versus pars plana vitrectomy for vitreous floaters". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6: CD011676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011676.pub2. PMC 6481890. PMID 28570745.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-05-01. Retrieved 2016-04-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Floaters – Ellex". Archived from the original on 2016-05-02. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- Delaney YM, Oyinloye A, Benjamin L (January 2002). "Nd:YAG vitreolysis and pars plana vitrectomy: surgical treatment for vitreous floaters". Eye (Lond). 16: 21–6. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6700026. PMID 11913884.

- Roth M, Trittibach P, Koerner F, Sarra G (Sep 2005). "[Pars plana vitrectomy for idiopathic vitreous floaters.]". Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 222 (9): 728–32. doi:10.1055/s-2005-858497. PMID 16175483.

- "Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) & floater only vitrectomy". Archived from the original on 2007-01-05. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- "Facts About Floaters". nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-12-07.

- "Surgery To Rid Eye "Floaters" Scrutinized". CBSNews HealthWatch. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- "Eye Floaters". MedicineNet. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- "Pharmacologic vitreolysis". One Clear Vision.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |