Sclera

The sclera,[help 1] also known as the white of the eye, is the opaque, fibrous, protective, outer layer of the human eye containing mainly collagen and some elastic fiber.[2] In humans, the whole sclera is white, contrasting with the coloured iris, but in other mammals the visible part of the sclera matches the colour of the iris, so the white part does not normally show. In the development of the embryo, the sclera is derived from the neural crest.[3] In children, it is thinner and shows some of the underlying pigment, appearing slightly blue. In the elderly, fatty deposits on the sclera can make it appear slightly yellow. Many people with dark skin have naturally darkened sclerae, the result of melanin pigmentation.

| Sclera | |

|---|---|

The sclera, as separated from the cornea by the corneal limbus. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Eye |

| System | Visual system |

| Artery | anterior ciliary arteries, long posterior ciliary arteries, short posterior ciliary arteries |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Sclera |

| MeSH | D012590 |

| TA | A15.2.02.002 |

| FMA | 58269 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The human eye is relatively rare for having a pale sclera (relative to the iris). This makes it easier for one individual to identify where another individual is looking, and the cooperative eye hypothesis suggests this has evolved as a method of nonverbal communication.

Structure

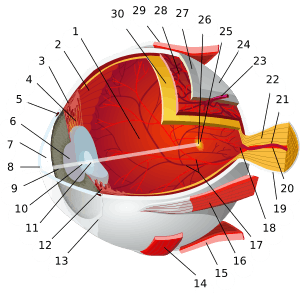

The sclera forms the posterior five-sixths of the connective tissue coat of the globe. It is continuous with the dura mater and the cornea, and maintains the shape of the globe, offering resistance to internal and external forces, and provides an attachment for the extraocular muscle insertions. The sclera is perforated by many nerves and vessels passing through the posterior scleral foramen, the hole that is formed by the optic nerve. At the optic disc the outer two-thirds of the sclera continues with the dura mater (outer coat of the brain) via the dural sheath of the optic nerve. The inner third joins with some choroidal tissue to form a plate (lamina cribrosa) across the optic nerve with perforations through which the optic fibers (fasciculi) pass. The thickness of the sclera varies from 1mm at the posterior pole to 0.3 mm just behind the rectus muscle insertions. The sclera's blood vessels are mainly on the surface. Along with the vessels of the conjunctiva (which is a thin layer covering the sclera), those in the episclera render the inflamed eye bright red.[4]

In many vertebrates, the sclera is reinforced with plates of cartilage or bone, together forming a circular structure called the sclerotic ring. In primitive fish, this ring consists of four plates, but the number is lower in many living ray-finned fishes, and much higher in lobe-finned fishes, various reptiles, and birds. The ring has disappeared in many groups, including living amphibians, some reptiles and fish, and all mammals.[5]

The eyes of all non-human primates are dark with small, barely visible sclera.

Histology

The collagen of the sclera is continuous with the cornea. From outer to innermost, the four layers of the sclera are:

- episclera

- stroma

- lamina fusca

- endothelium

The sclera is opaque due to the irregularity of the Type I[6] collagen fibers, as opposed to the near-uniform thickness and parallel arrangement of the corneal collagen. Moreover, the cornea bears more mucopolysaccharide (a carbohydrate that has among its repeating units a nitrogenous sugar, hexosamine) to embed the fibrils.

The cornea, unlike the sclera, has five layers. The middle, thickest layer is also called the stroma. The sclera, like the cornea, contains a basal endothelium, above which there is the lamina fusca, containing a high count of pigment cells.[4]

Sometimes, very small gray-blue spots can appear on the sclera, a harmless condition called scleral melanocytosis.

Function

Human eyes are somewhat distinctive in the animal kingdom in that the sclera is very plainly visible whenever the eye is open. This is not just due to the white colour of the human sclera, which many other species share, but also to the fact that the human iris is relatively small and comprises a significantly smaller portion of the exposed eye surface compared to other animals. It is theorized that this adaptation evolved because of our social nature as the eye became a useful communication tool in addition to a sensory organ. It is believed that the conspicuous sclera of the human eye makes it easier for one individual to identify where another individual is looking, increasing the efficacy of this particular form of nonverbal communication.[7] Animal researchers have also found that, in the course of their domestication, dogs have also developed the ability to pick up visual cues from the eyes of humans. Dogs do not seem to use this form of communication with one another and only look for visual information from the eyes of humans.[8]

Injury

Trauma

The bony area that makes up the human eye socket provides exceptional protection to the sclera. However, if the sclera is ruptured by a blunt force or is penetrated by a sharp object, the recovery of full former vision is usually rare. If pressure is applied slowly, the eye is actually very elastic. However, most ruptures involve objects moving at some velocity. The cushion of orbital fat protects the sclera from head-on blunt forces, but damage from oblique forces striking the eye from the side is not prevented by this cushion. Hemorrhaging and a dramatic drop in intraocular pressure are common, along with a reduction in visual perception to only broad hand movements and the presence or absence of light. However, low-velocity injury which does not puncture and penetrate the sclera requires only superficial treatment and the removal of the object. Sufficiently small objects which become embedded and which are subsequently left untreated may eventually become surrounded by a benign cyst, causing no other damage or discomfort.[9]

Thermal trauma

The sclera is rarely damaged by brief exposure to heat: the eyelids provide exceptional protection, and the fact that the sclera is covered in layers of moist tissue means that these tissues are able to cause much of the offending heat to become dissipated as steam before the sclera itself is damaged. Even relatively low-temperature molten metals when splashed against an open eye have been shown to cause very little damage to the sclera, even while creating detailed casts of the surrounding eyelashes. Prolonged exposure, however— on the order of 30 seconds— at temperatures above 45 °C (113 °F) will begin to cause scarring, and above 55 °C (131 °F) will cause extreme changes in the sclera and surrounding tissue. Such long exposures even in industrial settings are virtually nonexistent.[9]

Chemical injury

The sclera is highly resistant to injury from brief exposure to toxic chemicals. The reflexive production of tears at the onset of chemical exposure tends to quickly wash away such irritants, preventing further harm. Acids with a pH below 2.5 are the source of greatest acidic burn risk, with sulfuric acid, the kind present in car batteries and therefore commonly available, being among the most dangerous in this regard. However, acid burns, even severe ones, seldom result in loss of the eye.[9]

Alkali burns, on the other hand, such as those resulting from exposure to ammonium hydroxide or ammonium chloride or other chemicals with a pH above 11.5, will cause cellular tissue in the sclera to saponify and should be considered medical emergencies requiring immediate treatment.[9]

Clinical significance

Yellowing of the sclera is a visual symptom of jaundice. In very rare but severe cases of kidney failure and liver failure, the sclera may turn black. In cases of Osteogenesis Imperfecta, the sclera may appear to have a blue tint. The blue tint is caused by the showing of the Chorodial Veins.

See also

- Extraocular implant

- Scleral tattooing

Notes

- The word sclera (/ˈsklɛərə/ or /ˈsklɪərə/; both are common), plural sclerae (/ˈsklɛəri/ or /ˈsklɪəri/) or scleras, is from the Greek skleros, meaning hard.[1]

References

- Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary, Fourth Edition, Mosby-Year Book Inc., 1994, p. 1402

- Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. Dictionary of Eye Terminology. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company, 1990.

- Hermann D. Schubert. Anatomy of the Orbit "New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai - New York City - NYEE" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- "eye, human."Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 2009

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- Keeley, FW; Morin, JD; Vesely, S (November 1984). "Characterization of collagen from normal human sclera". Experimental Eye Research. 39 (5): 533–42. doi:10.1016/0014-4835(84)90053-8. PMID 6519194.

- Michael Tomasello, Brian Hare, Hagen Lehmann, Josep Call. "Reliance on head versus eyes in the gaze following of great apes and human infants: the cooperative eye hypothesis" http://www.chrisknight.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/eyes-cooperation.pdf

- Director and Producer: Dan Child, Executive Producer: Andrew Kohen (2010-01-06). "The Secret Life of the Dog". Horizon. BBC. BBC2.

- Peter G Watson (11 April 2012). "Chapter 9". The Sclera and Systemic Disorders. JP Medical Ltd. p. 293. ISBN 978-1-907816-07-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sclera. |

- Histology image: 08008loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Atlas image: eye_1 at the University of Michigan Health System—"Sagittal Section Through the Eyeball"

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia 002295