Evaluation & Testing

Congenital Zika Virus Infection

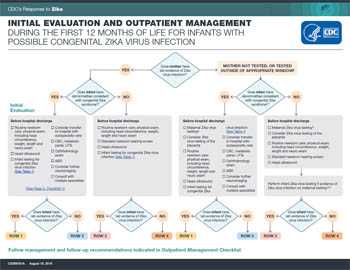

Initial Evaluation

Given that changes in the updated interim guidance for pregnant women will lead to fewer pregnant women without Zika symptoms being tested, it is critical that pediatricians ask about potential congenital Zika exposure for every newborn. Infants born to mothers with risk factors for Zika virus infection (travel to or residence in an area with risk of Zika during pregnancy or periconceptional period [8 weeks preconception (6 weeks after last menstrual period)] or sex without a condom during pregnancy or periconceptional period with a partner with travel to or residence in such an area) and who did not receive testing before delivery, should be assessed for Zika virus infection.

All infants born to mothers who have laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection* during pregnancy should receive the following initial evaluation before hospital discharge

- Comprehensive physical exam

- A neurologic assessment

- Standard newborn hearing screen

- Postnatal head ultrasound

- Zika virus laboratory testing

Infants with abnormalities consistent with congenital Zika syndrome should have additional interventions, as described in CDC’s Interim Guidance for the Evaluation and Management of Infants with Possible Congenital Zika Virus Infection — United States, August 2016 (1).

All infants born to mothers with: 1) possible Zika exposure without maternal Zika testing, 2) with negative testing but with ongoing maternal possible Zika virus exposure, 3) with negative test results on a specimen collected > 12 weeks after exposure, or 4) if there is concern about infant follow-up should receive the following initial evaluation as part of routine pediatric care.

- Comprehensive physical exam

- A neurologic assessment

- Standard newborn hearing screen

Based on the level of Zika exposure, the provider should consider whether further evaluation of the newborn is warranted for possible congenital Zika virus infection. If further evaluation is warranted, healthcare providers should consider

- Postnatal head ultrasound

- Ophthalmologic assessment

Zika virus laboratory testing of the infant should be considered based on evaluation findings.

Further evaluation for all infants with possible congenital Zika infection, based on the results of the clinical evaluation and laboratory testing, should be performed in accordance with CDC Interim Guidance for the Evaluation and Management of Infants with Possible Congenital Zika Virus Infection — United States, August 2016 (1).

Imaging

A head ultrasound is recommended before hospital discharge or within 1 month of birth for infants with possible Zika virus infection. For infants with a small or absent anterior fontanelle and poor visualization of the intracranial anatomy on ultrasound, other imaging (i.e., magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography) should be considered.

For infants born to mothers with: 1) possible Zika exposure without maternal Zika testing; 2) with negative testing but with ongoing maternal possible Zika virus exposure; or 3) with negative test results on a specimen collected > 12 weeks after exposure, a head ultrasound is not routinely recommended, but should be considered if further evaluation for possible congenital Zika infection is warranted.

Testing

Who to Test

Testing is recommended for

- infants born to mothers with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection during pregnancy, and

- infants who have abnormal clinical findings suggestive of congenital Zika virus syndrome and a maternal epidemiologic link§ suggesting possible exposure during pregnancy, regardless of maternal Zika virus test results.

Testing infants for congenital Zika virus infection should be performed within the first 2 days after birth, particularly in areas where Zika virus is currently circulating. If specimens are collected later, it may be difficult to distinguish congenital from postnatally acquired infection in areas with risk of Zika. Despite this limitation, testing specimens collected within the first few weeks to months after birth may still be useful to evaluate for possible congenital Zika virus infection, especially among infants born in areas without risk of Zika.

Testing could also be considered for

- Infants born to mothers with an epidemiologic link§ to an area with risk of Zika and who were not tested at all,

- Infants born to mothers with negative testing but with ongoing maternal possible Zika virus exposure, or

- Infants born to mothers whose negative testing was performed more than 12 weeks after the mother’s possible exposure.

The decision should be based on the risk factors for maternal exposure (type and location of exposure, length of exposure, presence of symptoms, protective measures taken, recall of mosquito bites or sexual exposure, patient preferences or concerns, and their state or local recommendations), as well as any findings from the initial clinical evaluation.

Each scenario is unique and healthcare providers can contact their health department for additional information. Guidelines will be updated as additional information becomes available.

Diagnosis & Testing

Zika virus infection can be diagnosed by a Zika virus RNA nucleic acid test (NAT) or through serologic testing. It has not been established which test is most reliable for a diagnosis of congenital infection in newborns. Therefore, both should both be performed.

A Zika virus RNA NAT should be performed on both infant serum and urine, and Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody should be performed on infant serum. Testing should be performed on infant specimens; testing of cord blood is not recommended. If cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is obtained for other studies, NAT testing for Zika virus RNA and Zika virus IgM should be performed on CSF. However, there are limited reports of congenital Zika virus infection in which CSF was the only sample testing positive (2). Therefore, healthcare providers should consider obtaining CSF for Zika virus RNA and IgM testing in infants with clinical findings of possible congenital Zika syndrome but whose initial laboratory tests are negative on serum and urine.

A Zika virus NAT positive result in an infant sample confirms the diagnosis of congenital Zika virus infection. Zika virus IgM detected in an infant, with a negative NAT result, should be interpreted as probable congenital Zika virus infection. If both Zika virus RNA NAT and Zika virus IgM results are negative, the infant is considered to be negative for congenital Zika virus infection, but test results of infant samples should be interpreted in the context of timing of infection during pregnancy, maternal serologic results, clinical findings consistent with Zika virus disease in infants, and additional confirmatory testing (plaque reduction neutralization testing [PRNT]).

If the infant’s initial sample is IgM positive, but PRNT was not performed on the mother’s sample, PRNT should be performed on the infant’s initial sample. However, PRNT cannot distinguish between maternal or infant antibodies. Maternal antibodies in the infant are expected to wane by 18 months. To confirm a congenital infection, PRNTs should be performed on a sample collected from an infant aged 18 months whose initial sample is IgM positive and neutralizing antibodies were detected by PRNT in either the infant’s or mother’s sample. If the infant’s initial sample is negative by both IgM ELISA and NAT but clinical concerns remain (e.g., microcephaly with negative evaluation for other known causes), PRNT at 18 months can be considered. If PRNT results at 18 months are negative, the infant is considered not to have congenital Zika virus infection. If PRNT results are positive, congenital Zika virus infection is presumed, but postnatal infection cannot be excluded, especially among infants living in an area with active Zika virus transmission. Guidance will be updated as additional information becomes available.

Infant test results**

| NAT | IgM | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Positive or Negative | Confirmed congenital Zika virus infection |

| Negative | Positive | Probable congenital Zika virus infection† |

| Negative | Negative | Negative for congenital Zika virus infection† |

Footnotes

**Infant serum, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid

† Laboratory results should be interpreted in the context of timing of infection during pregnancy, maternal serologic test results, clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome, and any confirmatory testing with plaque neutralization testing (PRNT)

Possible Limitations of Infant Laboratory Testing

The optimal methods to test for congenital Zika virus infection are unknown. Because data on testing for congenital Zika virus infection are limited, current CDC infant testing guidance is based on experience with other congenital infections. Two recent studies describe a small number of infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome in whom results of laboratory testing for Zika virus infection were negative (2, 3). Negative test results might occur in an infant with clinical findings of possible congenital Zika virus syndrome for several reasons:

- The clinical findings are due to another cause

- Testing was incomplete (e.g., RNA testing without antibody testing), performed on suboptimal specimens (e.g., cord blood rather than blood obtained from the infant), or performed too late (e.g., after RNA and IgM antibodies had cleared or waned) (4)

- The fetus did not mount an IgM antibody response; it is unknown if some fetuses infected early in gestation might not mount an IgM antibody response (5)

Maintain a Level of Suspicion

For infants without laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection but for whom suspicion for congenital Zika virus infection remains, healthcare providers should

- Evaluate for other causes of congenital infection

- Consider an ophthalmology exam and auditory brainstem response (ABR) hearing test before hospital discharge or within 1 month of birth

- Consider performing other evaluation and follow-up care in accordance with CDC interim guidance for the evaluation and management of infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection

Postnatal Zika Virus Infection

Criteria for testing will vary by state. However, postnatal Zika virus disease should be suspected in an infant or child aged <18 years who 1) traveled to or resided in an area with risk of Zika virus within the past 2 weeks or who might have been exposed to Zika virus through sexual contact with a partner who traveled to or resided in an area with risk of Zika, and 2) has ≥2 of the following manifestations: fever, rash, conjunctivitis, or arthralgia. Because transmission of Zika virus from mother to infant during delivery is possible, postnatal Zika virus disease should also be suspected in an infant during the first 2 weeks of life 1) whose mother, within approximately 2 weeks of delivery, was potentially exposed to Zika virus through travel to or residence in an area with risk of Zika or through sexual transmission, and 2) who has ≥2 of the following manifestations: fever, rash, conjunctivitis, or arthralgia.

Arthralgia can be difficult to detect in infants and young children and can manifest as irritability, walking with a limp (for ambulatory children), difficulty moving or refusing to move an extremity, pain on palpation, or pain with active or passive movement of the affected joint.

Diagnosis & Testing

Zika virus NAT should be performed on serum and urine collected <14 days after onset of symptoms in patients with suspected Zika virus disease. A positive Zika virus NAT confirms Zika virus infection. However, because Zika virus RNA in serum and urine decreases over time, a negative NAT does not rule out Zika virus infection; in this case, serologic testing should be performed. If Zika virus NAT results are negative for both specimens, serum should be tested by antibody detection methods.

Serology assays can also be used to detect Zika virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies, which typically develop toward the end of the first week of illness. A positive IgM result does not always indicate Zika virus infection and can be difficult to interpret because cross-reactivity with related flaviviruses (e.g., dengue, Japanese encephalitis, West Nile, yellow fever) can occur. A positive Zika virus IgM result may reflect previous vaccination against a flavivirus; previous infection with a related flavivirus; or current infection with a flavivirus, including Zika virus.

Plaque-reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) can be performed to measure virus-specific neutralizing antibodies to confirm primary flavivirus infections and differentiate from other viral illnesses. PRNT can be performed to measure virus-specific neutralizing antibodies to Zika virus, but neutralizing antibodies may still yield cross-reactive results in a person who was previously infected with another flavivirus, such as dengue, or has been vaccinated against yellow fever or Japanese encephalitis.

Ordering Tests

Zika virus testing is performed at many state and territorial health departments, at CDC, and at commercial laboratories that perform Zika testing using a validated assay with demonstrated analytical and clinical performance. Healthcare providers should contact their local, state, or territorial health department to facilitate testing. See Testing for Zika Virus for information on Zika testing.

Testing Challenges

Zika virus testing in infants and children has several challenges. NAT tests may not detect Zika virus RNA in an infant who had Zika virus infection in utero or a child if the period of viremia has passed. Serologic tests for Zika virus can be falsely positive because of cross-reacting antibodies against related flaviviruses (e.g., dengue and yellow fever viruses). Plaque-reduction neutralization testing (PRNT) can be performed to measure virus-specific neutralizing antibodies to Zika virus, but neutralizing antibodies may still yield cross-reactive results in infants due to maternal antibodies that were transferred to the infant. It is important to work closely with local, state, or territorial health departments to ensure the appropriate test is ordered and interpreted correctly.

More Information

Footnotes

*Laboratory evidence of maternal Zika virus infection includes 1) Zika virus RNA detected by nucleic acid testing (NAT) (e.g., rRT-PCR) in any clinical specimen; or 2) positive Zika virus IgM antibodies with confirmatory neutralizing antibody titers obtained via plaque reduction neutralization testing (PRNT). Confirmatory neutralizing antibody titers are needed in addition to IgM antibodies for laboratory evidence of maternal Zika virus infection.

§ An epidemiologic link includes travel to or residence in an area with risk of Zika or sex without a condom with a partner who traveled to or lived in such an area.

¶ For pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure who seek care >12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure, IgM antibody testing might be considered. However, a negative IgM antibody test or rRT-PCR result >12 weeks after symptom onset or possible exposure does not rule out recent Zika virus infection because IgM antibody and viral RNA levels decline over time.

References

- Russell K, Oliver SE, Lewis L, Barfield WD, Cragan J, Meaney-Delman D, Staples JE, Fischer M, Peacock G, Oduyebo T, Petersen EE, Zaki S, Moore CA, Rasmussen SA; Contributors. Update: Interim guidance for the evaluation and management of infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection — United States, August 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(33):870–878

- de Araujo TV, Rodrigues LC, de Alencar Ximenes RA, de Barros Miranda-Filho D, Montarroyos UR, de Melo AP, et al. Association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly in Brazil, January to May, 2016: Preliminary report of a case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16(12):1356–1363.

- Melo AS, Aguiar RS, Amorim MM, Arruda MB, Melo FO, Ribeiro ST, Batista AG, Ferreira T, Dos Santos MP, Sampaio VV, Moura SR, Rabello LP, Gonzaga CE, Malinger G, Ximenes R, de Oliveira-Szejnfeld PS, Tovar-Moll F, Chimelli L, Silveira PP, Delvechio R, Higa L, Campanati L, Nogueira RM, Filippis AM, Szejnfeld J, Voloch CM, Ferreira OC Jr, Brindeiro RM, Tanuri A. Congenital Zika virus infection: Beyond neonatal microcephaly. JAMA Neurol 2016;73(12):1407–1416.

- Honein MA, Dawson AL, Petersen EE, Jones AM, Lee EH, Yazdy MM, et al. Birth defects among fetuses and infants of US women with evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy. JAMA 2017;317(1):59–68.

- Alford CA, Foft JW, Blankenship WJ, Cassady G, Benton JW. Subclinical central nervous system disease of neonates: A prospective study of infants born with increased levels of IgM. J Pediatr 1969;75:1167–1178.

- Page last reviewed: August 14, 2017

- Page last updated: August 14, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir