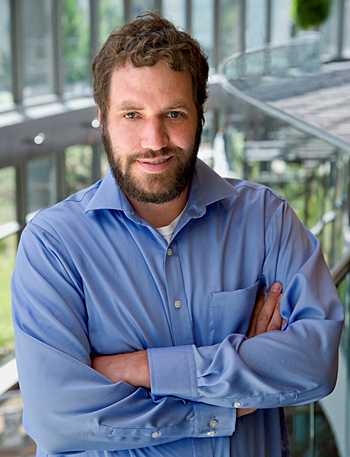

CDC’s Disease Detectives Respond to the 2014 Ebola Outbreak: Ben

CDC epidemiologist Ben

Ben in the field during a prior deployment for monkeypox in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Educational messages on Ebola are delivered in unique ways in Liberia

Disease Detective: Ben

CDC epidemiologist Benjamin could really use a haircut.

(And maybe a shave.)

Then again, such a low-maintenance look clearly has its uses, especially when he spends so much of his time in West Africa.

With undergraduate degrees in Biology and Education, Ben got his start teaching in the Peace Corps in Ghana before returning to Emory University to study public health. When asked why he chose to work at CDC, he explains, "I basically grew up at the CDC."

You see, Ben is known for more than just his shaggy style. He’s the son of not one, but two long-time CDC employees. "I always knew I’d be an epidemiologist, just from the dinner conversation," he says. "It’s odd being here as an adult, but this is sort of the family business."

When Ebola began to spread in Liberia, Ben’s background in education and prior Peace Corps experience were much-needed skills. He deployed in July and served on the ground as a health communications specialist. One of his primary objectives was to lay the groundwork for a health communication plan that could be used throughout the country, particularly around safe burial practices and improving healthcare-seeking behavior in resistant communities.

His job in Liberia was especially hard because of a strong underlying mistrust of government and authority. The government’s decision to require military escorts for healthcare workers in some cases inflamed resentment among the people he was trying to help. "It was hard to gain someone’s trust when a soldier had a gun pointed at them."

While he was there, the Ebola outbreak rapidly escalated in size and intensity. "It was difficult," he admits. "The situation evolved incredibly quickly while I was there. The messages we started with—that Ebola is real, and everyone should be reporting cases to healthcare workers—got lost in lots of fear."

One of the most difficult challenges was how to develop messages to get people to quickly change their behavior.

"In this outbreak, burials are a big problem due to unsafe methods of handling bodies," he says. "We wanted to try to encourage cremation as a safer method of handling the dead."

Ben started off by meeting with religious leaders, pastors, and families, and asking their views about cremation. "They thought it was something foreigners did. But when we started talking more about it, it became clear that cremation itself was not viewed as culturally inappropriate. The method of handling the body was not as important to them as the ceremony itself."

An unexpected effect of the widespread attempt to share Ebola prevention messages was a growing obsession with handwashing in Liberia.

"The country organized a very big push about handwashing. It was a rule that all public places, such as supermarkets and stores, had to have a handwashing station with chlorine water, but nobody gave guidance. Most stations lacked running water, and many used highly concentrated chlorine solutions without appropriate dilution with water. Taxi cab drivers were hosing their cars down with concentrated bleach. Normally when you work overseas, you become used to a wide range of odors. By the time I left Monrovia in August, the entire city smelled like bleach."

Another significant challenge for Ben was time spent away from family. As a father of two, Ben admits he missed his son’s fourth birthday on this trip.

"I still feel pretty bad about that," he says. "And my son still refuses to sleep in his own bed because he slept in my wife’s bed while I was away. On the other hand, my son likes telling people Daddy is working in Africa."

He also says that coming back and sitting at a desk at the CDC has not been an easy process. "Complex humanitarian emergencies can be over-stimulating environments," he explains. "When you are in a high stress situation where things are changing constantly, coming back can be a bit of a shock."

Despite the strain, when asked if he would go back, he does not hesitate. "Yes. When I saw the gravity of the situation, I was glad I went. Not many people are in the position to offer help, but I was."

It will take a lot more hands like Ben’s on the ground before this outbreak is brought under control.

And if he goes back again soon, maybe waiting on that haircut isn’t such a bad idea after all.

- Page last reviewed: September 8, 2014

- Page last updated: September 8, 2014

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir