Cerebral atrophy

Cerebral atrophy is a common feature of many of the diseases that affect the brain.[1] Atrophy of any tissue means a decrement in the size of the cell, which can be due to progressive loss of cytoplasmic proteins. In brain tissue, atrophy describes a loss of neurons and the connections between them. Atrophy can be generalized, which means that all of the brain has shrunk; or it can be focal, affecting only a limited area of the brain and resulting in a decrease of the functions that area of the brain controls. If the cerebral hemispheres (the two lobes of the brain that form the cerebrum) are affected, conscious thought and voluntary processes may be impaired.

Some degree of cerebral shrinkage occurs naturally with age. The human brain completes growth and attains its maximum mass at around age 25; it gradually loses mass with each decade of life, although the rate of loss is comparatively tiny until the age of 60, when approximately 0.5 to 1% of brain volume is lost per year. By age 75, the brain is an average of 15% smaller than it was at 25. Some areas of the brain such as short-term memory are affected more than others and men lose more brain mass overall than women.

Brain atrophy does not affect all regions with the same intensity as shown by neuroimaging.[2]

Symptoms

Many diseases that cause cerebral atrophy are associated with dementia, seizures, and a group of language disorders called the aphasias. Dementia is characterized by a progressive impairment of memory and intellectual function that is severe enough to interfere with social and work skills. Memory, orientation, abstraction, ability to learn, visual-spatial perception, and higher executive functions such as planning, organizing and sequencing may also be impaired. Seizures can take different forms, appearing as disorientation, strange repetitive movements, loss of consciousness, or convulsions. Aphasias are a group of disorders characterized by disturbances in speaking and understanding language. Receptive aphasia causes impaired comprehension. Expressive aphasia is reflected in odd choices of words, the use of partial phrases, disjointed clauses, and incomplete sentences.

Possible causes

The pattern and rate of progression of cerebral atrophy depends on the disease involved.

Injury

- Stroke, loss of brain function due to a sudden interruption of blood supply in the brain

- Traumatic brain injury

- Corticosteroid use (There appears to be correlations between degree of dosing with corticosteroids and cerebral atrophy)[3]

- Environmental pollutants [4]

Diseases and disorders

- Alzheimer's disease (High resolution MRI scans have shown the progression of cerebral atrophy in Alzheimer's disease)[5]

- Cerebral palsy, in which lesions (damaged areas) may impair motor coordination

- Senile dementia, fronto-temporal dementia, and vascular dementia

- Pick’s disease, causes progressive destruction of nerve cells in the brain

- Huntington's disease, and other genetic disorders that cause build-up of toxic levels of proteins in neurons

- Leukodystrophies, such as Krabbe disease, which destroy the myelin sheath that protects axons

- Multiple sclerosis, which causes inflammation, myelin damage, and lesions in cerebral tissue

- Epilepsy, in which lesions cause abnormal electrochemical discharges that result in seizures

- Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other eating disorders

- Malnutrition, caused by lack or excess of nutrition from foods

- Type II diabetes, where the body does not use insulin properly resulting in high blood sugar

- Bipolar disorder,[6] significant loss of brain tissue during manic episodes; however it's not verified whether the episodes cause brain tissue loss or vice versa

- Schizophrenia[7]

- Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies, such as Kearns-Sayre syndrome, which interfere with the basic functions of neurons

- Posterior cortical atrophy: In the most posterior area of the brain lies the visual cortex, the area of the brain where visual information is received and processed. When cortical atrophy occurs in this brain area due to neurodegeneration, the first symptom is impairment in vision. A common vision impairment seen in patients with posterior cortical atrophy is simultanagnosia, where a person is unable to see multiple locations at once or to quickly shift attention between these locations. When looking at images of a brain suffering from posterior cortical atrophy, one can see a loss in volume of the dorsal and ventral visual pathways, where visual stimuli is brought to the visual cortex and integrated information is sent back out to other areas of the brain. Because this disorder results in visual impairments, there is often a missed or delayed diagnosis, as the assumption is that there is a problem is in the eyes when the reality is that the problem is all the way in the back of the brain.[8]

- Prion diseases, a group of invariably fatal encephalopathies that cause the progressive death of neurons.

Infections

Where an infectious agent or the inflammatory reaction to it destroys neurons and their axons, these include...

- Encephalitis, acute inflammation in the brain

- Neurosyphilis, an infection in the brain or spinal chord

- AIDS, disease of the immune system

Drug-induced

- Alcohol [9]

- Neuroleptic

Diagnosis

Neurofilament light chain

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a fluid that is found exclusively in the brain and spinal cord that circulates between sections of the brain offering an extra layer of protection. Studies have shown that biomarkers in the CSF and plasma can be tracked for their presence in different parts of the brain—and their presence can tell us about cerebral atrophy. One study took advantage of biomarkers, namely one called neurofilament light chain (NFL), in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurofilament light chain is a protein that is important in the growth and branching of neurons—cells found in the brain. In Alzheimer’s Disease, neurons will stop working or die in a process called neurodegeneration. By tracking NFL, researchers can see this neurodegeneration, which this study showed was associated with brain atrophy and later cognitive decline in Alzheimer's patients. Other biomarkers like Ng – a protein important in long-term potentiation and memory – have been tracked for their associations with brain atrophy as well, but NFL had the greatest association.[10]

Measures

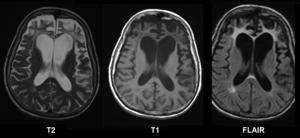

CT and MRI are most commonly used to observe the brain for cerebral atrophy. A CT scan takes cross sectional images of the brain using X-rays, while an MRI uses a magnetic field. With both measures, multiple images can be compared to see if there is a loss in brain volume over time.[12]

Difference from hydrocephalus

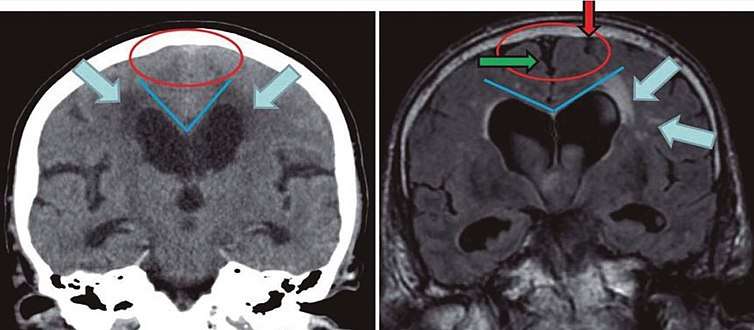

Cerebral atrophy can be hard to distinguish from hydrocephalus because both cerebral atrophy and hydrocephalus involve an increase in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume. In cerebral atrophy, this increase in CSF volume comes as a result of the decrease in cortical volume. In hydrocephalus, the increase in volume happens due to the CSF itself.[12]

|

| ||

| Normal pressure hydrocephalus | Brain atrophy | |

|---|---|---|

| Preferable projection | Coronal plane at the level of the posterior commissure of the brain. | |

| Modality in this example | CT | MRI |

| CSF spaces over the convexity near the vertex (red ellipse | Narrowed convexity ("tight convexity") as well as medial cisterns | Widened vertex (red arrow) and medial cisterns (green arrow) |

| Callosal angle (blue V) | Acute angle | Obtuse angle |

| Most likely cause of leucoaraiosis (periventricular signal alterations, blue arrows |

Transependymal cerebrospinal fluid diapedesis | Vascular encephalopathy, in this case suggested by unilateral occurrence |

Treatment and prevention

Unfortunately, cerebral atrophy is not usually preventable, however there are steps that can be taken to reduce the risks such as controlling your blood pressure, eating a healthy balanced diet including omega-3's and antioxidants, and staying active mentally, physically, and socially.[14]

Reversibility of cerebral atrophy

While most cerebral atrophy is said to be irreversible there are some recent studies that show this is not always the case. A child who was treated with ACTH originally showed atrophy, but four months after treatment the brain was seemingly normal again.[15]

Chronic alcoholism is known to be associated with cerebral atrophy in addition to motor dysfunction and impairment in higher brain function. Because some of the behavioral deficits have shown improvement after abstinence from alcohol, a study looked to see if cerebral atrophy could be reversed too. Researchers took CT scans of the 8 study participants in order to measure cortical volume over time. Although decrease in atrophy does not equate clinical improvement, the CT scans of 50% of participants showed partial improvement, giving hope that cerebral atrophy could be a reversible process.[9]

See also

References

- "Cerebral Atrophy Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- Brainmarkers.com Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Steroids and Apparent Cerebral Atrophy on Computed Tomograph... : Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography

- "IQs are falling - and have been for years".

- Fox Nick C, Schott Jonathan M (2004). "Imaging cerebral atrophy: normal ageing to Alzheimer's disease". The Lancet. 363 (9406): 392–394. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15441-X. PMID 15074306.

- "Study links manic depression with brain tissue loss". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- Andreasen, Nancy C.; Liu, Dawei; Ziebell, Steven; Vora, Anvi; Ho, Beng-Choon (2013-06-01). "Relapse Duration, Treatment Intensity, and Brain Tissue Loss in Schizophrenia: A Prospective Longitudinal MRI Study". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (6): 609–615. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12050674. ISSN 0002-953X. PMC 3835590. PMID 23558429.

- Maia, da Silva MN, Millington RS, Bridge H, James-Galton M, Plant GT (2017). "Visual Dysfunction in Posterior Cortical Atrophy". Front Neurol. 8: 389. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00389. PMC 5561011. PMID 28861031.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Partially reversible atrophy in abstinent chronic alcoholics".

- Pereira JB, Westman E, Hansson O (October 2017). "Association between cerebrospinal fluid and plasma neurodegeneration biomarkers with brain atrophy in Alzheimer's disease". Neurobiology of Aging. 58: 14–29. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.06.002. PMID 28692877.

- Velickaite, V.; Giedraitis, V.; Ström, K.; Alafuzoff, I.; Zetterberg, H.; Lannfelt, L.; Kilander, L.; Larsson, E-M.; Ingelsson, M. (2017). "Cognitive function in very old men does not correlate to biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease". BMC Geriatrics. 17 (1): 208. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0601-6. ISSN 1471-2318. PMC 5591537. PMID 28886705. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- "Cerebral Atrophy".

- Damasceno, Benito Pereira (2015). "Neuroimaging in normal pressure hydrocephalus". Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 9 (4): 350–355. doi:10.1590/1980-57642015DN94000350. ISSN 1980-5764. PMC 5619317. PMID 29213984.

- "Cerebral Atrophy: Causes". Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- Gordon Neil (2008). "Apparent Cerebral Atrophy in Patients on Treatment with Steroids". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 22 (4): 502–506. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1980.tb04355.x. PMID 6250932.

%2C_posterior_atrophy_(PA)_and_frontal_cortical_atrophy_(fGCA).png)