Encephalitis lethargica

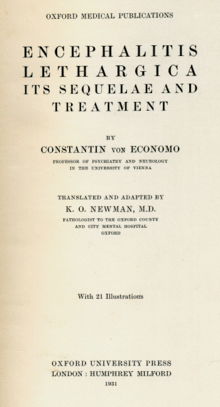

Encephalitis lethargica is an atypical form of encephalitis. Also known as "sleeping sickness" or "sleepy sickness" (distinct from tsetse fly-transmitted sleeping sickness), it was first described in 1917 by the neurologist Constantin von Economo[1][2] and the pathologist Jean-René Cruchet.[3]

| Encephalitis lethargica | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Nellysa disease; Economo's disease |

| |

| First described by Constantin von Economo. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Causes | Unknown |

| Frequency | Unknown |

The disease attacks the brain, leaving some victims in a statue-like condition, speechless and motionless.[4] Between 1915 and 1926,[5] an epidemic of encephalitis lethargica spread around the world. Nearly five million people were affected, a third of whom died in the acute stages. Many of those who survived never returned to their pre-existing "aliveness".

They would be conscious and aware – yet not fully awake; they would sit motionless and speechless all day in their chairs, totally lacking energy, impetus, initiative, motive, appetite, affect or desire; they registered what went on about them without active attention, and with profound indifference. They neither conveyed nor felt the feeling of life; they were as insubstantial as ghosts, and as passive as zombies.[6]

No recurrence of the epidemic has since been reported, though isolated cases continue to occur.[7][8]

Signs and symptoms

Encephalitis lethargica is characterized by high fever, sore throat, headache, lethargy, double vision, delayed physical and mental response, sleep inversion and catatonia.[4][9] In severe cases, patients may enter a coma-like state (akinetic mutism). Patients may also experience abnormal eye movements ("oculogyric crises"),[10] parkinsonism, upper body weakness, muscular pains, tremors, neck rigidity, and behavioral changes including psychosis. Klazomania (a vocal tic) is sometimes present.[11]

Cause

The causes of encephalitis lethargica (EL) are uncertain.[12]

Some studies have explored its origins in an autoimmune response,[4] and, separately or in relation to an immune response, links to pathologies of infectious disease — viral and bacterial,[4] e.g., in the case of influenza, where a link with encephalitis is clear.[13] Postencephalic Parkinsonism was clearly documented to have followed an outbreak of EL following 1918 influenza pandemic; evidence for viral causation of the Parkinson's symptoms is circumstantial (epidemiologic, and finding influenza antigens in EL patients), while evidence arguing against this cause is of the negative sort (e.g., lack of viral RNA in postencephalic parkinsonian brain material).[13] In reviewing the relationship between influenza and EL, McCall and coworkers conclude, as of 2008, that while "the case against influenza [is] less decisive than currently perceived… there is little direct evidence supporting influenza in the etiology of EL," and that "[a]lmost 100 years after the EL epidemic, its etiology remains enigmatic."[8] Hence, while opinions on the relationship of EL to influenza remain divided, the preponderance of literature appears skeptical.[8][14]

German neurologist Felix Stern who examined hundreds of EL patients during the 1920s pointed out that the EL would happen chronically. The early symptom would be dominated by sleepiness or wakefulness. A second symptom would lead to an oculogyric crisis. The third symptom would be recovery, followed by a Parkinson-like symptom. If patients of Stern followed this course of disease, he diagnosed them with EL. Stern suspected EL to be close to polio without evidence. Nevertheless, he experimented with the convalescent serum of survivors of the first acute symptom. He vaccinated patients with early stage symptoms and told them that it might be successful. Stern is author of the 1920s definitive book Die Epidemische Encephalitis (1920 and 2nd ed. 1928). Stern was driven to suicide during the Holocaust by the German state, his research forgotten.[15]

In 2010, in a substantial Oxford University Press compendium reviewing the historic and contemporary views on EL, its editor, Joel Vilensky of the Indiana University School of Medicine, quotes Pool, writing in 1930, who states, "we must confess that etiology is still obscure, the causative agent still unknown, the pathological riddle still unsolved…", and goes on to offer the following conclusion, as of that publication date:

Does the present volume solve the "riddle" of EL, which… has been referred to as the greatest medical mystery of the 20th century? Unfortunately, no: but inroads are certainly made here pertaining to diagnosis, pathology, and even treatment."[16]

Subsequent to publication of this compendium, an enterovirus was discovered in EL cases from the epidemic.[17] In 2012, Oliver Sacks acknowledged this virus as the probable cause of encephalitis lethargica.[18]

Diplococcus has been implicated as a cause of EL.[19]

Diagnosis

There have been several proposed diagnostic criteria for encephalitis lethargica. One, which has been widely accepted, includes an acute or subacute encephalitic illness where all other known causes of encephalitis have been excluded. Another diagnostic criterion, suggested more recently, says that the diagnosis of encephalitis lethargica "may be considered if the patient’s condition cannot be attributed to any other known neurological condition and that they show the following signs: influenza-like signs; hypersomnolence (hypersomnia), wakeability, opthalmoplegia (paralysis of the muscles that control the movement of the eye), and psychiatric changes."[20]

Treatment

Modern treatment approaches to encephalitis lethargica include immunomodulating therapies, and treatments to remediate specific symptoms.[21]

There is little evidence so far of a consistent effective treatment for the initial stages, though some patients given steroids have seen improvement.[22] The disease becomes progressive, with evidence of brain damage similar to Parkinson's disease.[23]

Treatment is then symptomatic. Levodopa (L-DOPA) and other anti-parkinson drugs often produce dramatic responses; however, most people given L-DOPA experience improvements that are short lived.[24][25]

Notable cases

Notable cases include:

- Muriel "Kit" Richardson (née Hewitt), first wife of actor Sir Ralph Richardson, died of the condition in October 1942 having first shown symptoms in 1927–28.

- There is speculation that Adolf Hitler may have had encephalitis lethargica when he was a young adult (in addition to the more substantial case for Parkinsonism in his later years).[26][27][28][29]

- Mervyn Peake (1911–1968), author of the Gormenghast books, began his decline towards death which was initially attributed to encephalitis lethargica with Parkinson's disease-like symptoms, although others have later suggested his decline in health and eventual death may have been due to Lewy body dementia.[30][31]

- Rosita Renard (1894-1949), Chilean pianist, contemporary of Claudio Arrau and student of Martin Krause

References

- Economo's disease at Who Named It?

- K. von Economo. Encepahlitis lethargica. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift, May 10, 1917, 30: 581-585. Die Encephalitis lethargica. Leipzig and Vienna, Franz Deuticke, 1918.

- Cruchet R, Moutier J, Calmettes A. « Quarante cas d'encéphalomyélite subaiguë » Bull Soc Med Hôp Paris 1917;41:614-6.

- Dale, Russell C.; Church, Andrew J.; Surtees, Robert A.H.; Lees, Andrew J.; Adcock, Jane E.; Harding, Brian; Neville, Brian G. R.; Giovannoni, Gavin (2004). "Encephalitis Lethargica Syndrome: 20 New Cases and Evidence of Basal Ganglia Autoimmunity". Brain. 127 (1): 21–33. doi:10.1093/brain/awh008. PMID 14570817. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Encephalitis lethargica" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Awakenings, Oliver Sacks, p. 14

- Stryker Sue B. "Encephalitis lethargica: the behavior residuals". Training School Bulletin. 22 (1925): 152–7.

- Reid, A.H.; McCall, S.; Henry, J.M.; Taubenberger, J.K. (2001). "Experimenting on the Past: The Enigma of von Economo's Encephalitis Lethargica". J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 60 (7): 663–670. doi:10.1093/jnen/60.7.663. PMID 11444794.

- KOCH, CHRISTOF (March–April 2016). "Sleep without End". Scientific American Mind. 27 (2): 22–25. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0316-22 – via EBSCOhost.

- Vilensky, J.A.; Goetz, C.G.; Gilman, S. (2006). "Movement Disorders Associated with Encephalitis Lethargica: A Video Compilation". Mov. Disord. 21 (1, January): 1–8. doi:10.1002/mds.20722. PMID 16200538.

- Jankovic, J.; Mejia, N.I. (2006). "Tics Associated with Other Disorders". Adv. Neurol. 99: 61–8. PMID 16536352.

- McCall, S.; Vilensky, J.A.; Gilman, S.; Taubenberger, J.K. (2008). "The Relationship Between Encephalitis Lethargica and Influenza: A Critical Analysis". J. Neurovirol. 14 (3, May): 177–185. doi:10.1080/13550280801995445. PMC 2778472. PMID 18569452.

- Haeman, Jang; Boltz, D.; Sturm-Ramirez, K.; Shepherd, K.R.; Jiao, Y.; Webster, R.; Smeyne, Richard J. (2009). "Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Influenza Virus Can Enter the Central Nervous System and Induce Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (33, August 10): 14063–14068. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900096106. PMC 2729020. PMID 19667183. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Vilensky, J.A.; Foley, P.; Gilman, S. (2007). "Children and Encephalitis Lethargica: A Historical Review". Pediatr. Neurol. 37 (2, August): 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.04.012. PMID 17675021. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Auf der Spur der Schlaf-Epidemie". Spektrum.de (in German). 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- Vilensky, J.A.; Gilman, S. (2010). "Introduction". In Vilensky, Joel A. (ed.). Encephalitis Lethargica: During and After the Epidemic. Oxford, ENG: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–7, esp. 6f. ISBN 978-0190452209. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Dourmashkin, Robert R.; Dunn, Glynis; Castano, Victor; McCall, Sherman A. (2012-01-01). "Evidence for an enterovirus as the cause of encephalitis lethargica". BMC Infectious Diseases. 12: 136. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-136. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 3448500. PMID 22715890.

- Letter from Oliver Sacks to Professor Joel A. Vilensky, 9 Sept 2012.

- "Mystery of the forgotten plague". 27 July 2004 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Easton, Ava. "Encephalitis Lethargica". The Encephalitis Society. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Lopez-Alberola, R; Georgiou, M; Sfakianakis, G.N.; Singer, C.; Papapetropoulos, S. (2009). "Contemporary Encephalitis Lethargica: Phenotype, Laboratory Findings and Treatment Outcomes". J. Neurol. 256 (3, March): 396–404. doi:10.1007/s00415-009-0074-4. PMID 19412724.

- Blunt, S.B.; Lane, R.J.; Turjanski, N.; Perkin, G.D. (1997). "Clinical Features and Management of Two Cases of Encephalitis Lethargica". Mov. Disord. 12 (3): 354–9. doi:10.1002/mds.870120314. PMID 9159730.

- Kohnstamm P (1934). Über die Beteiligung der beiden Schichten der Substantia nigra am Prozeß der Encephalitis epidemica. J Psychol Neurol 46(1): 22-37.

- "Encephalitis Lethargica Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. August 9, 2018.

- Sacks, Oliver (1973). Awakenings. Duckworth & Co. ISBN 978-0-375-70405-5.

- Lieberman, A (April 1996). "Adolf Hitler Had Post-Encephalitic Parkinsonism". Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2 (2): 95–103. doi:10.1016/1353-8020(96)00005-3. PMID 18591024.

- Boettcher, L.B.; Bonney, P.A.; Smitherman A.D.; Sughrue, M.E. (2015). "Hitler's Parkinsonism". Neurosurg Focus. 39 (1, July): E8. doi:10.3171/2015.4.FOCUS1563. PMID 26126407.

- Gupta, R; Kim, C; Agarwal, N; Lieber, B & Monaco, E.A. (2015). "Understanding the Influence of Parkinson's Disease on Adolf Hitler's Decision-Making During World War II". World Neurosurg. 84 (5, November): 1447–1452. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.06.014. PMID 26093359.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Rosen, Denis (2010). "Review: "Asleep: the Forgotten Epidemic That Remains One of Medicine's Greatest Mysteries" [Molly Caldwell Crosby". J. Clin. Sleep Med. 6 (3, 15 June): 299. PMC 2883045.

- Demetrios J. Sahlas (2003). "Dementia With Lewy Bodies and the Neurobehavioral Decline of Mervyn Peake". Arch. Neurol. 60 (6): 889–92. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.6.889. PMID 12810496.

- McMillan, Roy; Peake (20 July 2011) [1959]. Butcher Sara (ed.). Publisher's Liner Notes on Mervyn Peake for 'Titus Alone' (Liner Notes/ Reference Guide for Abridged Audiobook of Titus Alone). Audible.com (PDF, Liner Notes) (Abridged, Audio ed.). Germany: Naxos Audiobooks. p. 7. ISBN 978-184-379-542-1. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

But the plays were not the financial winners he had hoped for, and he suffered another nervous breakdown in 1957. This led to the more evident display of the symptoms of a type of Parkinson’s Disease which, alongside the effects of encephalitis lethargica that he contracted in childhood, was slowly to kill him over more than a decade.

Further reading

- Sacks O (1983). "The origin of 'Awakenings'". Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.). 287 (6409): 1968–1969. doi:10.1136/bmj.287.6409.1968. PMC 1550182. PMID 6418286.

- Reid, A.H.; McCall, S.; Henry, J.M.; Taubenberger, J.K. (2001). "Experimenting on the Past: The Enigma of von Economo's Encephalitis Lethargica". J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 60 (7): 663–670. doi:10.1093/jnen/60.7.663. PMID 11444794.

- Vilensky, J.A.; Foley, P.; Gilman, S. (2007). "Children and Encephalitis Lethargica: A Historical Review". Pediatr. Neurol. 37 (2, August): 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.04.012. PMID 17675021.

- Vilensky, Joel A., ed. (2010). Encephalitis Lethargica: During and After the Epidemic. Oxford, ENG: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190452209. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Crosby, Molly Caldwell (2010). 'Asleep: The Forgotten Epidemic that Remains One of Medicine's Greatest Mysteries. New York, NY, USA: Penguin/Berkley. Describes the history of the disease, and the epidemic of the 1920s.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- Mystery of the Forgotten Plague: BBC news item about the tracing of the infectious agent in encephalitis lethargica