We need you! Join our contributor community and become a WikEM editor through our open and transparent promotion process.

Congestive heart failure

From WikEM

(Redirected from Cardiogenic pulmonary edema)

Contents

Background

- Assume valvular problem in new-onset CHF

- Assume valve thrombosis in CHF with a prosthetic valve

- Do not give vasodilators in aortic stenosis, HOCM; yes in mitral regurgitation

Classification

- Systolic: poor contraction (↓EF) and decreased forward flow

- Diastolic: good contraction (normal EF) but stiff ventricles and poor filling

- Left-sided: LV failure, poor organ perfusion, dyspnea from backup in lung

- Right-sided: peripheral edema, JVD, hepatomegaly

- Most common cause is left-sided failure

NYHA Classes

- No symptoms

- Symptoms with every day activity

- Severely limits activity or symptoms with minimal activity

- Symptoms at rest

Etiology

- Acute coronary syndrome (CAD)

- Hypertension

- Cardiomyopathy

- Valvular emergency

- High-output heart failure

- Peripartum cardiomyopathy

- Cardiac tamponade

- Dysrhythmias

Clinical Features

History & Physical Examination[1]

Different types of presentations:

- Hypotensive Heart Failure

- Least common, worst prognosis

- shortness of breath, pulmonary edema, narrow pulse pressure, signs of poor end-organ perfusion, altered mental status, cool peripheries, decreased urine output, increased HR, sBP < 90 mmHg

- Normotensive Heart Failure

- Develops over days to weeks

- Weight gain, peripheral edema, less shortness of breath, +/- rales

- Hypertensive Heart Failure

- Most common, presses rapidly

- sBP > 140 mmHg, preserved LV function, marked shortness of breath, minimal weight gain, rales, increased HR, pulmonary edema on CXR

- Acute Pulmonary Edema

- Severe respiratory distress, relative hypertension, cool dipahoretic skin, +/- rales, JVD (94% specific, 39% sensitive), +/- peripheral edema, S3 (99% specific)

Differential Diagnosis

- Cardiovascular

- Pulmonary

- Other

- Pure volume overload

- Renal Failure

- Post-Transfusion

- Sepsis

- Pure volume overload

Causes of CHF Decompensation

- Medication noncompliance

- Dietary noncompliance

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- MI

- Valvular Dysfunction

- Arrhythmias

- Infection

- Inappropriate medications (e.g., negative inotropes)

- Fluid overload

- Missed dialysis

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Anemia

- Alcohol Withdrawal

Evaluation

- CBC (rule out anemia)

- Chemistry

- ECG

- Digoxin level

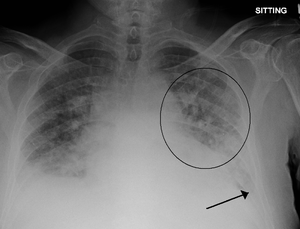

- CXR

- Cephalization

- Curly B lines (thick and horizontal)

- Interstitial edema

- Pulmonary venous congestion

- Pleural effusion

- Alveolar edema

- Cardiomegaly

- Troponin/CK

- Ultrasound

- Bedside to assess global function, B lines, assessment of IVC

- Formal TTE/TEE

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)[2]

- Biologically active metabolite of proBNP (released from ventricles in response to increased volume/pressure)

- Utility is controversial and may not affect patient centered outcomes[3]

- May be trended to gauge treatment response in acute decompensated CHF

- May have false negative with isolated diastolic dysfunction

- Measurement

- <100 pg/mL: Negative for acute CHF (Sn 90%, NPV 89%)

- 100-500 pg/mL: Indeterminate (Consider differential diagnosis and pre-test probability)

- >500 pg/mL: Positive for acute CHF (Sp 87%, PPV 90%)

NT-proBNP[4][5][6]

- N-terminal proBNP (biologically inert metabolite of proBNP)

- <300 pg/mL → CHF unlikely

- CHF likely in:

- >450 pg/mL in age < 50 years old

- >900 pg/mL in 50-75 years old

- >1800 pg/mL in > 75 years old

Differential Diagnosis (Elevated BNP)

BNP In Obese Patients

- Visceral fat expansion leads to increased clearance of active natriuretic peptides[7]

- Obese patients also frequently treated for hypertension or coronary artery disease which may also contribute to lower BNP levels

Interpretation

- In one study of 204 patients with acute CHF, an inverse relationship between BMI and BNP was noted. The standard cutoff of 100pg/mL resulted in a 20% false-negative rate[8]

- Analysis of a subgroup of patients with documented BMI from the Breathing Not Properly study showed that a lower cutoff was more appropriate to maintain 90% sensitivity in obese and morbidly obese patients (54pg/mL)[9]

Management

Acute Pulmonary Edema and Hypertensive Heart Failure

See Pulmonary Edema or Sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema (SCAPE)

Hypotensive Heart Failure

Inotropic Agents

- Dobutamine generally first line

- Milrinone if patient on beta-blockers

- Consider in severe LV dysfunction and low output syndrome

- Diminished peripheral perfusion and end organ damage

- Vasodilatory treatment inadequate response or limited by symptomatic hypotension

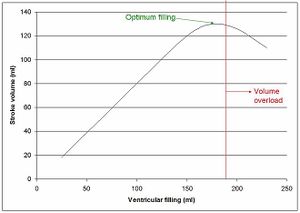

- Must have obvious evidence of elevated filling pressures

- JVD, noncollapsing IVC, etc

- Inotropes are not indicated in setting of preserved systolic function

Heart Failure Without Pulmonary Edema

UNLOAD+

- Upright Position

- Nitrates

- Do not use with sildenafil, severe AS, or if right-sided MI

- Start sublingual nitroglycerin 0.4mg delivered over 4 min = 0.10mg/min

- If no improvement IV NTG drip, start 0.3-0.5mcg/kg/min, but may increase to 3-5mcg/kg/min

- Keep BP >95

- Consider nitroprusside 0.3 mcg/kg/min if hypertension or NTG ineffective

- Lasix

- Hold if no symptoms of fluid overload

- Give nitrates first

- Give double home dose, or up to 2.5x dose.

- If lasix 40mg po qd, then lasix 40-100mg IV

- Oxygen

- ACEI

- Afterload reduction

- Enalaprilat at 0.004mg/kg as IVB or 1mg drip over 2hr

- Avoid in pregnancy, hyperK+, angioedema

- Digoxin

- Decompensated HF

- Digoxin and Amiodarone are the only medications indicated for use in decompensated HF for rate control if needed[10]

- Evidence suggests that treating rate in acutely ill patients including CHF leads to worse outcomes[11]

- Compensated HF (not acutely symptomatic from failure)

- May benefit from a fib rate control, but calcium-channel blockers and beta-blockers first line, goal of < 85 bpm per RACE II trial

- Diltiazem low and slow at 5mg/hr

- AVOID in severe heart failure, preexcitation syndrome

- AVOID in significant hypotension

- Metoprolol 2.5 - 5.0mg over 2 min, then q5 as needed to max of 15mg

- Esmolol 0.5mg/kg bolus over 1 min, then 50 mcg/kg/min, may increase q30 min by 50 mcg/kg/min

- Decompensated HF

Medications to Avoid

- Anti-dysrhythmics other than digoxin and amiodarone

- calcium-channel blockers - worsen HF

- NSAIDs - sodium retention, worsen toxicity of diuretics and ACE-I

- Thiazolidinediones - worsen HF

- Morphine - chart reviews show increased morbidity in ADHF patients[12][13]

Disposition

Admission Criteria

CCORT

- 7 day mortality risk score calculator for patients presenting to the ED with decompensated HF

- http://www.ccort.ca/calculator.aspx

AHCPR '00

- ACS

- Pulmonary edema/respiratory distress

- O2 sat < 90% on room air

- Severe complicating illness

- CHF refractory to outpatient therapy

- Anasarca

- Symptomatic hypotension or syncope

- Arrhythmia (e.g. new a. fib)

- Inadequate outpatient support

CHF Drug Target Doses

- ACE inhibitor

- Lisinopril 5mg qd start; 20mg qd goal

- Captopril 25mg tid start; 100mg tid goal

- Benazepril 10mg qd start; 40mg qd goal

- ARB

- Beta-blocker

- Carvedilol 3.125mg bid start; 25mg bid goal (50mg bid goal if weight > 85 kg)

- Metoprolol ER 12.5mg qd start; 190mg qd goal

- Others

- Hydralazine/isosorbid dinitrate 10-20mg (1 tab) tid start; 100-80mg (5 tabs) goal for black patients with NYHA III-IV already on BB and ACEi

- Spironolactone 25mg qd start; 50mg qd goal for indications:

- LVEF < 30% with NYHA II

- LVEF < 35% with NYHA III-IV

- LVEF < 40% post-MI, goal ACE-I, symptomatic CHF, or DM

External Links

See Also

References

- ↑ Peacock W. Chapter 57: Congestive Heart Failure and Acute Pulmonary Edema. In: Tintinalli J. Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine. A comprehensive study guide. 7th ed. 2011: 405-415.

- ↑ Maisel AS, Krishnaswamy P, Nowak RM, et al. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(3):161-167. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020233.

- ↑ Carpenter CR et al. BRAIN NATRIURETIC PEPTIDE IN THE EVALUATION OF EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT DYSPNEA: IS THERE A ROLE? J Emerg Med. 2012 Feb; 42(2): 197–205.

- ↑ Januzzi JL, van Kimmenade R, Lainchbury J, et al. NT-proBNP testing for diagnosis and short-term prognosis in acute destabilized heart failure: an international pooled analysis of 1256 patients: the International Collaborative of NT-proBNP Study. Eur Heart J. 2006 Feb. 27(3):330-7.

- ↑ Kragelund C, Gronning B, Kober L, Hildebrandt P, Steffensen R. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and long-term mortality in stable coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2005 Feb 17. 352(7):666-75.

- ↑ Moe GW, Howlett J, Januzzi JL, Zowall H,. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide testing improves the management of patients with suspected acute heart failure: primary results of the Canadian prospective randomized multicenter IMPROVE-CHF study. Circulation. 2007 Jun 19. 115(24):3103-10.

- ↑ Clerico A, Giannoni A, Vittorini S, Emdin M. The paradox of low BNP levels in obesity. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;17(1):81-96. doi:10.1007/s10741-011-9249-z.

- ↑ Krauser DG, Lloyd-Jones DM, Chae CU, et al. Effect of body mass index on natriuretic peptide levels in patients with acute congestive heart failure: A ProBNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department (PRIDE) substudy. Am Heart J. 2005;149(4):744-750. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.010.

- ↑ Daniels LB, Clopton P, Bhalla V, et al. How obesity affects the cut-points for B-type natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of acute heart failure. Results from the Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study. Am Heart J. 2006;151(5):999-1005. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.10.011.

- ↑ January CT, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: Executive summary a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 64(21):2246-2280.

- ↑ Scheuermeyer FX, et al. Emergency department patients with atrial fibrillation or flutter and an acute underlying medical illness may not benefit from attempts to control rate or rhythm. Ann Emerg Med. 2015; 65(5):511-522.e2.

- ↑ Peacock WF, Hollander JE, Diercks DB, Lopatin M, Fonarow G, Emerman CL. Morphine and outcomes in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE analysis. Emerg Med J. 2008 Apr;25(4):205-9.

- ↑ Ellingsrud C, Agewall S. Morphine in the treatment of acute pulmonary oedema--Why? Int J Cardiol. 2016 Jan 1;202:870-3.