We need you! Join our contributor community and become a WikEM editor through our open and transparent promotion process.

Acute asthma exacerbation

From WikEM

For pediatrics patients see Asthma (peds)

Contents

Background

- Quickly establish severity of current presentation and history of severe exacerbations (e.g. need for ICU, intubation, etc)

- Identify any treatable precipitant (e.g. pneumonia, URI, GERD, esposure to irritants)

- Status asthmaticus is a life-threatening form of asthma in which progressively worsening reactive airways are unresponsive to usual appropriate therapy that leads to pulmonary insufficiency.

Clinical Features

- Dyspnea, wheezing, and cough

- Prolonged expiration

- Accessory muscle use

- Sign of impending ventilatory failure

- Paradoxical respiration

- Chest deflation and abdominal protrusion during inspriation

- Altered mental status

- "Silent chest"

- Paradoxical respiration

Differential Diagnosis

Shortness of breath

Emergent

- Pulmonary

- Airway obstruction

- Anaphylaxis

- Aspiration

- Asthma

- Cor pulmonale

- Inhalation exposure

- Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema

- Pneumonia

- Pneumocystis Pneumonia (PCP)

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Tension pneumothorax

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis acute exacerbation

- Cardiac

- Other Associated with Normal/↑ Respiratory Effort

- Other Associated with ↓ Respiratory Effort

Non-Emergent

- ALS

- Ascites

- Uncorrected ASD

- Congenital heart disease

- COPD exacerbation

- Fever

- Hyperventilation

- Neoplasm

- Obesity

- Panic attack

- Pleural effusion

- Polymyositis

- Porphyria

- Pregnancy

- Rib fracture

- Spontaneous pneumothorax

- Thyroid Disease

Evaluation

- Normally a clinical diagnosis

Consider CXR if

- Fever > 102.2

- Worsening symptoms

- Poor response to medications/treatment

- 1st wheeze

- Chest pain

Management

Albuterol

Favor continuous nebulization to decrease the chance of admission when compared to intermittent dosing[1]

- Nebulizer

- Intermitent: 2.5-5mg q20min x3, then 2.5-10mg q1-4hr as needed OR

- Continuous: 0.5mg/kg/hr (max 15mg/hr)[2]

- If using intermitent nebs at home PTA, start on continuous

- MDI

- 4-8 puffs q20min up to 4h, then q1-4hr as needed

- Levalbuterol is pure R-enantiomer, whereas racemic albuterol as above is 50:50 mix of R and S albuterol

- Levalbuterol at 5x the cost, may not warrant the small benefits seen in some studies

- In severe asthma exacerbation, be aware of lactic acidosis that develops due to pathology and the added lactic acidosis from albuterol

- Manifests as worsening respiratory distress, tachypnea, compensatory increase in ventilation

- Ensure adequate intravascular volume, but carefully volume expand as acute asthma may increase ADH secretion[5]

- Rarely, clinically important hypokalemia, alongside hyperglycemia and leukocytosis, may result from repeated beta agonists and sympathomimetics[6]

Ipratropium[7][8]

- 0.25-0.5mg q20min x2-3 doses

- Only shown to the effective in the acute setting to reduce hospitalization rates and improve lung function

- No benefit of adding to inpatient, hospitalized regimens

Steroids

Should be given in the first hour with effects to reduce admission[9]

- Dexamethasone

- As effective as prednisone especially in children [10]

- Single dose dexamethasone may be equally effective to 5 days of prednisone in adults[11]

- 0.6mg/kg IV or PO (max 16mg); 2nd dose 24hr later

- Prednisone

- 40-60mg/day in one or two divided doses x5d

- Methylprednisolone

- 1mg/kg IV q 4–6hr

- Only use IV if cannot tolerate PO since equal effectiveness between dosing routes[12]

- Inhaled corticosteroids may be considered as a rescue effort for severe asthma, given over a 90 min period[13][14]

- Nebulized fluticasone 500 µg q15 min

- Nebulized budesonide 800 µg q30 min

Magnesium

- 25-75 mg/kg over 30 min (1-2 gm IV in most adults)

- Duration of action approximately 20 min, beware of hypotension in rapid administration due to smooth muscle relaxation mechanism

- In patients with moderate to severe asthma there is a decreased rate of admission with an NNT of 2[9]

Other Beta-Agonists

- Inhalation is preferred route of administration, but adequate drug delivery to small airways may be hampered in severe attacks

- Terbutaline and epinephrine can be administered IM/IV/SubQ

- Need to monitor for arrhythmias, tachycardia, hypertension, cardiac ischemia[15]

Epinephrine

- 1:1000 0.01 mg/kg (max 0.5mg) subQ or IM Q20min x3

- Nebulized racemic epinephrine 0.03 mL/kg (2.25% solution) diluted in 3-5 mL NS via jet nebulizer q3-4hr prn shown to be as safe as nebulized albuterol[16]

Terbutaline

- Longer-acting beta2-agonist promoting bronchodilation

- Caution in elderly/CHF with greater potential for cardiotoxicity

- 0.25mg subQ/IM q20min x 3

- Then followed by infusion at 1 µg/kg/min, titrated up by increments of 1 to max of 10 1 µg/kg/min

- Elevated troponins q4hrs during infusion, more common in cTnI vs. cTnT, with EKG changes of ischemia should prompt re-evaluation for stopping infusion[17]

- Some experts have nebulized IV form[18][19]

- 5 mg of IV form terbutaline

- However, significantly higher cost than albuterol

Non-invasive ventilation

- Consider as alternative to intubation

- Alleviates muscle fatigue which leads to larger tidal volumes

- May drive nebulized treatments deeper into airways

- Maximize inspiratory support

- Inspiratory pressure 8

- PEEP 0-3, only enough to match patient's auto-PEEP

Heliox

- 60 to 80% helium is blended with 20 to 40% oxygen

- Heliox improves non laminar flow and may increases the diffusion of carbon dioxide by improving ventilation[20]

Intubation

- Relative indications include worsening hypercapnea, exhaustion, altered mental status, CO2 narcosis without any specific number endpoint on blood gases

- Consider induction with Ketamine

- Provides bronchodilation and sedation however it does promote secretions

- Ketamine is the preferred induction agent for intubation in an asthmatic.

- Dosing 1-2mg/kg

- Ventilation of asthmatic patients requires deep sedation

- Ventilation settings

- Assist-control ventilation

- Resp rate

- Start slow to avoid air-trapping

- RR ~ 8-10 in adults

- Make sure plateau pressure <30, with inspiratory hold

- If >30 must lower respiratory rate

- May require "permissive hypoventilation"

- Sacrifice MV for full exhalation

- Lower I:E ratio

- Low peak pressure/avoidance of breath stacking more important than correcting CO2 [22]

- Tidal volume 6-8cc/kg ideal wt

- PEEP 0

- Flow rate 80-100L/min

- Keep FiO2 minimum to achieve SpO2 > 90%

- Use bronchodilators even when intubated

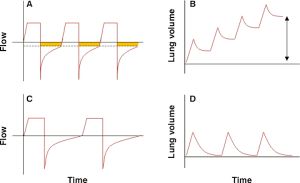

- Monitor for breath stacking (inspiratory holds, plateau pressures)

- Most common cause of post-intubation hypotension[23]

- Check ventilator tracing

Asthma Arrest

- Disconnect ventilator

- Decompress chest

- Consider bilateral chest tubes

- Fluid bolus

Outpatient Treatment

| Severity | Day Sx | Night Sx | Treatment (WHO 2008 Formulary)[24] |

| Mild intermittent, > 80% peak flow | < 2/wk | < 2/mo | Albuterol MDI 100-200 mcg prn qid |

| Mild persistent, > 80% peak flow | >2/wk | >2/mo | Albuterol MDI 100-200 mcg prn qid

PLUS Beclometasone 100-250 mcg bid |

| Moderate persistent, 60-80% peak flow | Daily with exacerbations weekly | > 1/wk | Albuterol MDI 100-200 mcg prn qid

PLUS Beclometasone 100-500 mcg bid PLUS Salmeterol inhaled 50 mcg bid |

| Severe persistent, < 60% peak flow | Continuous daily | Frequent | Albuterol MDI 100-200 mcg prn qid

PLUS Beclometasone 1mg bid (high dose) PLUS Salmeterol inhaled 50 mcg bid PLUS (if needed) SR theophylline, leukotriene antagonist, or PO prednisolone with taper |

Disposition

- Discharge - if symptoms resolve

- Often, patients will still have mild wheezing, but should have complete resolution of tachypnea, hypoxia, and work of breathing if being discharged

- Discharge versus admit based on physician judgment if some symptoms persist and adequate home support

- A short course of glucocorticoids (prednisone in adults or dexamethasone in children (0.6mg/kg) decreases change of relapse [25])

- Often, patients will still have mild wheezing, but should have complete resolution of tachypnea, hypoxia, and work of breathing if being discharged

- Admit - if symptoms persist or are severe

- Classically disposition is based on peak flow measurements, such results are often not available in the ED

- Predicted = (30 x age (yrs)) + 30

- PEF >70% predicted → high likelihood of successful discharge

- PEF <40% predicted → should be admitted

See Also

- Modified pulmonary index score (MPIS)

- Ventilation settings

- Deterioration after intubation

- COPD exacerbation

- Asthma (peds)

External Links

References

- ↑ Camargo CA et al. Continuous versus intermittent beta- agonists for acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD001115. PMID: 14583926.

- ↑ National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP), “Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma,” Clinical Practice Guidelines, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH Publication No. 08-4051, prepublication 2007; available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm.

- ↑ Ralston ME, Euwema MS, Knecht KR, Ziolkowski TJ, Coakley TA, Cline SM. Comparison of levalbuterol and racemic albuterol combined with ipratropium bromide in acute pediatric asthma: a randomized controlled trial. J Emerg Med. 2005;29(1):29-35.

- ↑ Qureshi F, Zaritsky A, Welch C, Meadows T, Burke BL.Clinical efficacy of racemic albuterol versus levalbuterol for the treatment of acute pediatric asthma. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(1):29-36.

- ↑ Qureshi F. Management of children with acute asthma in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15(3):206-214.

- ↑ Leikin JB et al. Hypokalemia after pediatric albuterol overdose: a case series. Am J Emerg Med. 1994 Jan;12(1):64-6.

- ↑ Goggin N, Macarthur C, Parkin PC. Randomized trial of the addition of ipratropium bromide to albuterol and corticosteroid therapy in children hospitalized because of an acute asthma exacerbation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(12):1329-1334.

- ↑ Rodrigo GJ, Rodrigo C. The role of anticholinergics in acute asthma treatment: an evidence-based evaluation. Chest. 2002;121(6):1977-1987.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Rowe BH et al. Magnesium sulfate for treating exac- erbations of acute asthma in the emergency depart- ment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001490. PMID: 10796650.

- ↑ Keeney, et al. Dexamethasone for Acute Asthma Exacerbations in Children: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2013-2273

- ↑ Rehrer MW et al. A randomized controlled noninferiority trial of single dose of oral dexamethasone versus 5 days of oral prednisone in acute adult asthma. Ann Emerg Med 2016 Apr 22.

- ↑ Rowe BH, Keller JL, Oxman AD. Effectiveness of steroid therapy in acute exacerbations of asthma: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. Jul 1992;10(4):301-10

- ↑ Rodrigo GJ. Inhaled Corticosteroids as Rescue Medication in Acute Severe Asthma. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2008;4(6):723-729.

- ↑ Volovitz B. Inhaled budesonide in the management of acute worsenings and exacerbations of asthma: a review of the evidence. Respir Med. 2007 Apr;101(4):685-95.

- ↑ Scarfone RJ, Friedlaender EY.beta2-Agonists in acute asthma: the evolving state of the art. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18(6):442-427.

- ↑ Plint AC, Osmond MH, Klassen TP. The efficacy of nebulized racemic epinephrine in children with acute asthma: a randomized, double-blind trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(10):1097-1103.

- ↑ Kalyanaraman M et al. Serial cardiac troponin concentrations as marker of cardiac toxicity in children with status asthmaticus treated with intravenous terbutaline. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011 Oct;27(10):933-6.

- ↑ Lin YZ, Hsieh KH, Chang LF, Chu CY.Terbutaline nebulization and epinephrine injection in treating acute asthmatic children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1996;7(2):95-99.

- ↑ Rodrigo GJ, Nannini LJ. Comparison between nebulized adrenaline and beta2 agonists for the treatment of acute asthma. A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(2):217-222.

- ↑ Kass JE: Heliox redux. Chest 2003; 123:673.

- ↑ Adnet F, Dhissi G, Borron SW, et al. Complication profiles f adult asthmatics requiring paralysis during mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(11):1729-1736.

- ↑ Darioli, et al. Mechanical Controlled hypoventilation in status asthmaticus. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984; 129 (3) 385-7

- ↑ Williams TJ, Tuxen DV, Scheinkestel CD, et al. Risk factors for morbidity in mechanically ventilated patients with acute severe asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(3):607-615.

- ↑ Stuart MC et al. WHO Model Formulary 2008. ../docss/WMF2008.pdf.

- ↑ Chapman K. Effect of a short course of prednisone in the prevention of early relapse after the emergency room treatment of acute asthma. NEJM. 1991;324(12):788