We need you! Join our contributor community and become a WikEM editor through our open and transparent promotion process.

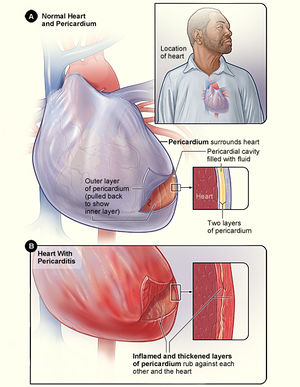

Pericarditis

From WikEM

Contents

Background

Etiology

- Idiopathic (25-85%)

- Infection (up to 20%, including viral, bacterial, TB)

- Malignancy: heme, lung, breast

- Uremia

- Post radiation

- Connective tissue disease

- Drugs: procainamide, hydralazine, methyldopa, anticoagulants

- Cardiac injury (can see up to weeks later): post MI (Dressler's syndrome), thoracic trauma, aortic dissection

- Troponin elevation may indicate a concurrent myocarditis which predispose to risk of CHF or arrhythmia. [1]

Clinical Features

- Pleuritic chest pain

- Radiates to chest, back, left trapezius

- Diminishes with sitting up/leaning forward

- Shortness of breath

- Especiallyif concommitant pleural effusion

- Hypotension/extremis if cardiac tamponade

- Fever, chills, myalgias (systemic signs with viral infection)

- Friction rub

Differential Diagnosis

ST Elevation

- Myocardial infarct (STEMI)

- Post-MI (ventricular aneurysm pattern)

- Previous MI with recurrent ischemia in same area

- Wellens' syndrome

- Coronary artery vasospasm (eg, Prinzmetal's angina)

- Coronary artery dissection

- Drugs of abuse (eg, cocaine, crack, meth)

- Pericarditis

- Myocarditis

- Aortic dissection in to coronary

- LV aneurysm

- Early repolarization

- Left bundle branch block

- Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)

- Pneumomediastinum

- Pneumothorax

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Myocardial tumor

- Myocardial trauma

- External compression of artery

- Medications: Tricyclic (TCA) toxicity, Digoxin

- RV pacing (appears as Left bundle branch block)

- Hyperkalemia (only leads V1 and V2)

- Hypothermia ("Osborn J waves")

- Brugada syndrome

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

- AVR ST elevation

Evaluation

Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Pericarditis[2]

- Need 2 of the following

- Chest pain (typically sharp and pleuritic, improved by sitting up and leaning forward)

- Pericardial friction rub

- New or worsening pericardial effusion

- Suggestive ECG changes

Work-Up

- ECG

- Labs

- WBC, CMP, ESR, CRP, trop

- Consider TSH, ANA based on clinical suspicion

- CXR

- Bedside Ultrasound to rule out effusion

- ~2/3 of cases will have pericardial effusion[3]

- Can consider CT or cardiac MRI if workup non-diagnostic and clinical suspicion persists

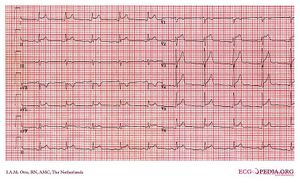

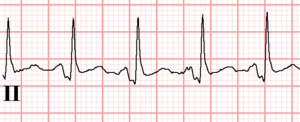

ECG

Classical Teachings with Caveats Below

- Must differentiate from STEMI (classical teachings are not specific enough to do that)

- Classically pericarditis has diffuse ST-elevations

- However, pericarditis may generate localized ST-elevations

- Pericarditis should never produce ST-depressions (suggestive of reciprocal changes), except in V1 and aVR

- Classically pericardidits has concave upwards STE

- Classically pericardititis has PR-depression in viral pericarditis (or PR-elevation in AVR)

- Less reliable in post-MI patients and those with baseline ECG abnormalities

- PR-depression is often early and transient in pericarditis

- In STEMI, PR-depression is associated with atrial injury, though usually not as marked as in viral pericarditis[4]

- PR-elevation in aVR may also be present in STEMI and is infrequently seen in constrictive pericarditis

Other Findings

- Leads II and III

- STE II > STE III favors pericarditis

- STE III > STE II very strongly favors STEMI

- STD not in aVR or V1 (reciprocol changes) suggestive of STEMI

- May see low voltage/alternans if effusion present

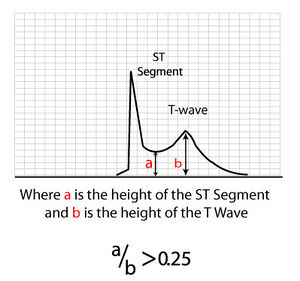

- If early repolarization confounding interpretation check ST:T ratio

- If (STE)/(T height) in V6 or I > 0.25, then it is likely pericarditis

- If predominantly inferior STE, ST-depression in aVL is sensitive for STEMI[5]

- Spodick's sign, purportedly in ~80% - downsloping TP segment, often best seen in lead II and lateral precordial leads[6]

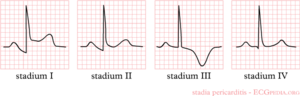

Stages of Progression

- Stage I:

- Global concave up ST elevation in all leads (esp V4-6, I, II) in all leads except in aVR, V1 and III

- PTa depression (depression between the end of the P-wave and the beginning of the QRS- complex)

- Stage II:

- "pseudonormalisation," ST to baseline, big T's, PR dep

- Stage III:

- T wave flatten then inversion

- Stage IV:

- Return to baseline

STEMI vs Pericarditis

| Disease | STEMI | Pericarditis |

| Pain | Costant | Varies with motion |

| Fever | No | Yes |

| ST changes | focal | Diffuse elevation |

| Reciprocal changes | Yes | No |

| Q waves | Yes | No |

| Pulmonary edema | Sometimes | No |

| Wall motion | Abnormal | Normal |

Management

Initial Treatment

- NSAIDS or Aspirin (ASA)first line treatment (in absence of contraindications) for viral or idiopathic pericarditis.[7]

- Cholchicine add cholchicine to NSAIDs as first line treatment for viral/idiopathic acute and recurrent pericarditis to improve remission rates and prevent recurrence.[8]

- Patients >70kg - 0.6mg PO BID x 3 months

- Patients<70kg - 0.6mg PO Daily x 3 months

- Glucocorticoid therapy second line agent for viral/idiopathic pericarditis, can consider low-moderate doses for patients with contraindications to NSAIDs or persistent symptoms despite appropriate therapy with NSAIDs + colchicine for at least 1 week. Also used for etiologies that are steroid responsive diseases.

- Prednisone 0.2 to 0.5mg/kg of body weight per day for 2 weeks with gradual tapering[9]

Recurrent or Refractory

For recurrent or refractory cases consider colchicine and or steroids although literature suggests it can be used as first line[10]

- Colchicine

- Patients >70kg - 0.6mg PO BID x 6 months

- Patients<70kg - 0.6mg PO Daily x 6 months

- If patients develop serious diarrhea decrease their dosing to the next weight class or stop treatment.

Contraindications to Colchicine[11]

- Tuberculous

- Neoplastic pericarditis

- Liver disease or aminotransferase levels ≥1.5x upper limits of normal

- Creatinine >2.5mg/dL (>221 umol/L)

- Myopathy or CK > upper limits of normal

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Life expectancy ≤18 months

- Pregnancy or lactation

Uremic Pericarditis

- The definitive treatment is dialysis

Tamponade

- Tamponade requires Pericardiocentesis

Disposition

- Hospitalization is not necessary in most cases

- Consider admission for:

Complications

- Pericardial Effusion and Tamponade

- Recurence

- Usually weeks to months after initial episode

- Management is same

- Constrictive Pericarditis

- Related to etiology; increased risk with bacterial pericarditis, rare with viral/idiopathic etiology

- Restrictive picture with pericardial calcifications on CXR, thickened on TTE

- Treat with pericardial window

See Also

- ST segment elevation

- STEMI

- Myocardial Infarction Complications

- Mattu ECG Case: Sept 3, 2012 - Pericarditis vs. STEMI

References

- ↑ LeWinter MM, et al. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 18;371(25):2410-6. PMID: 25517707.

- ↑ Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and Treatment of Pericarditis: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2015;314(14):1498–506.

- ↑ LeWinter MM. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 18;371(25):2410-6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1404070. Review.

- ↑ Wang K, Asinger RW, and Marriott HJL. ST-segment Elevation in Conditions Other than Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2128-35.

- ↑ Bischof JE, Worrall C, Thompson P, et al. ST depression in lead aVL differentiates inferior ST-elevation myocardial infarction from pericarditis. Am J Emerg Med. 2016; 34(2):149-154.

- ↑ Chaubey VK and Chhabra L. Spodick’s Sign: A Helpful Electrocardiographic Clue to the Diagnosis of Acute Pericarditis. Perm J. 2014 Winter; 18(1): e122.

- ↑ Imazio M. A randomized trial of colchicine for acute pericarditis.N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 17;369(16):1522-8 PDF

- ↑ ImazioM, BobbioM, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2012-2016.

- ↑ Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, et al. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericar- ditis: high versus low doses: a nonran- domized observation. Circulation 2008; 118:667-71.

- ↑ Imazio M.Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the CORE (COlchicine for REcurrent pericarditis) trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Sep 26;165(17):1987-91.

- ↑ Imazio M. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases.Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.PDF