Information on the Survivability of the Ebola Virus in Medical Waste

Page Summary

Who this is for: U.S. hospital leadership and those responsible for waste management.

What this is for: This guidance is intended to provide additional clarity on options for waste management practices to appropriately dispose of Ebola waste.

How to use: Use this document as background on the Ebola virus, including physical and chemical agents that can eradicate the virus. For additional guidance, see Ebola-Associated Waste Management, Interim Guidance for Environmental Infection Control in Hospitals for Ebola Virus, and Interim Guidance for the U.S. Residence Decontamination for Ebola Virus Disease (Ebola) and Removal of Contaminated Waste.

Background

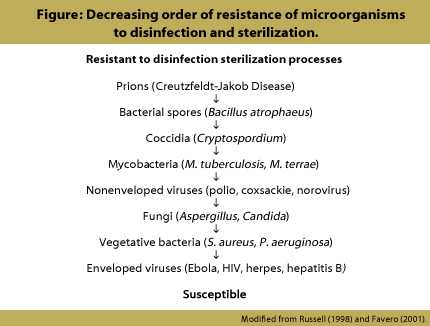

The Ebola virus is an “enveloped virus,” meaning that the core of the virus is surrounded by a lipoprotein outer layer. Enveloped viruses such as Ebola are more susceptible to destruction with a number of physical and chemical agents than viruses without lipoprotein envelopes (Figure).

For the purposes of this document, any waste generated in the care of patients under investigation (PUIs) or patients with confirmed Ebola virus disease (EVD) is considered a Category A infectious substance.

Physical Agents/Heat

Physical agents that can eradicate Ebola virus include heat, sunlight, ultraviolet light, E-Beam, and Gamma Rays.1

Killing suspected Ebola virus on or attached to materials can be done by

- Heating to 60°C (140°F) for 60 minutes;

- Heating to 72-80°C (162° – 176°F) for 30 minutes;

- Submersing the material in boiling water for five minutes.2

This can be achieved by treating materials suspected of being contaminated with Ebola in an autoclave under a “validated waste cycle” to 121°C (250°F) for at least 30 minutes. Depending on the load and packaging, the treatment uses more than enough heat and time to kill the virus. The autoclave runs should include a process control to show that the cycle was performed effectively. The Autoclave cycles should be checked at some frequency with biological indicator (spores) as a quality assurance measure to show that the waste cycles are achieving desired results.

Another heat treatment is incineration. Incinerators run at extremely high temperatures, well above the relatively low temperatures needed to kill Ebola virus. Incineration would be the best method for large or bulky items, such as mattresses. Incineration that reduces waste to ash at any temperature kills Ebola virus.3 The ash produced via incineration is NOT hazardous with respect to microbial pathogens.

Chemical Agents

Ebola virus also can be killed by many common chemical agents. Chemical agents that will kill the virus include bleach, detergents, solvents, alcohols, ammonia, aldehydes, halogens, peracetic acid, peroxides, phenolics, and quaternary ammonium compounds.4

Ebola virus can be killed with hospital-grade disinfectants (such as household bleach) when used according to the label instructions. A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-registered hospital disinfectant with a label claim for a nonenveloped virus (norovirus, rotavirus, adenovirus, poliovirus) can be used to disinfect environmental surfaces in rooms of PUIs or patients with confirmed EVD. Please see EPA’s Disinfectants for Use Against the Ebola Virus.

Additional Information

There is limited evidence of Ebola virus transmission through the environment or an inanimate object that may be contaminated during patient care with infectious organisms and serve in their transmission (bed rails, doorknobs, laundry).5 Ebola virus has not been found on surfaces in the absence of visible blood in the patient care environment.6 Frequently touched surfaces should be cleaned and disinfected on a regular basis to help reduce the risk of contact with contaminated surfaces. In addition, spills of biological fluids should be immediately cleaned and disinfected. Disinfectants should also be added to bagged waste.

References

1. Elliott LH, McCormick JB, Johnson KM. Inactivation of Lassa, Marburg, and Ebola viruses by gamma irradiation. J Clin Microbiol. 1982 Oct;16(4):704-8.

2. Mitchell SW, McCormick JB. Physicochemical inactivation of Lassa, Ebola, and Marburg viruses and effect on clinical laboratory analyses. J Clin Microbiol 1984; 20(3):486-9.

3. Barbeito MS, Taylor LA, Seiders RW. Microbiologic evaluation of a large volume air incinerator [PDF -6 pages]. Appl Microbiol 1968; 16:490-5.

4. Chepurnova AA, Bakulina LF, Dadaeva AA, Ustinova EN, Chepurnova TS, Baker JR, Jr,. Inactivation of Ebola virus with a surfactant nanoemulssion. Acta Tropica 2003; 87:315-320.

5. CDC Interim Guidance for Environmental Infection Control in Hospitals for Ebola Virus. 2014.

6. Bausch DG, Towner JS, Dowell SF, Kaducu F, Lukwiya M, Sanchez A, et al. Assessment of the risk of Ebola virus transmission from bodily fluids and fomites. J Infect Dis 2007; 196:S142–7.

7. Ribner BS. Treating patients with Ebola virus infections in the US: lessons learned. Presented at IDWeek, October 8, 2014. Philadelphia PA.

8. Favero MS, Bond WW. Chemical disinfection of medical and surgical materials. In: Block SS, ed. Disinfection, sterilization, and preservation. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001:881-917.

9. Mitchell SW, McCormick JB. Physicochemical inactivation of Lassa, Ebola, and Marburg viruses and effect on clinical laboratory analyses. J Clin Microbiol 1984; 20(3):486-9.

10. Russell AD. Bacterial resistance to disinfectants: present knowledge and future problems. J Hosp Infect 1998;43:S57-68.

11. Rutala WA, Weber DA, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guidelines for disinfection and sterilization in healthcare facilities, 2008 [PDF – 158 pages] . Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008.

- Page last reviewed: February 12, 2015

- Page last updated: February 12, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir