Reproductive Health: Then and Now

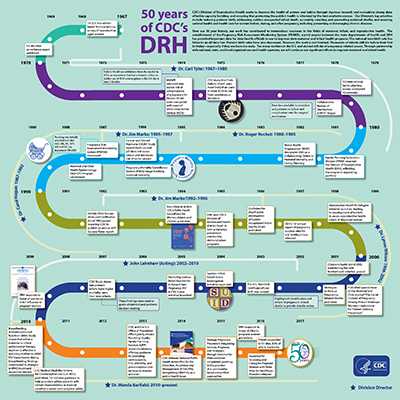

Since reproductive health activities first began at CDC in 1967, what has grown into today’s Division of Reproductive Health has helped improve the health of mothers and babies in the U.S. and around the world.

Seizing opportunities to work together, generations of committed public health practitioners and advisors, physicians, epidemiologists, statisticians, and other specialists have contributed their unique skills and expertise to create positive impact in maternal and child health. Some of the successes we’ve shared include:

- The national infant mortality rate has dropped 70%.

In 1970, the infant mortality rate was 20.01. By 2014, the rate had dropped to just 5.82. That represents a 70 percent decline. - The national teen birth rate has fallen to an all-time low.

In 1970, about 68 teens in every 1,000 had a baby. Today, that rate has dropped to 22.3—the lowest rate ever seen and a decline of almost 70 percent. - Our public health capacity for maternal and child health has expanded at the state, local, tribal, and territorial levels.

Through programs like the Maternal and Child Health Epidemiology Program (MCHEP) and the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), DRH has provided other organizations and agencies with the tools to translate data to action to improve health outcomes for women, infants, children, and families. Since 1987, MCHEP has assigned more than 35 senior epidemiologists to 36 states and 6 public health agencies and organizations. PRAMS began collecting data from 6 sites in 1986 and has since grown to collect data from 51 sites in 2017.

We are now at an exciting crossroads in the field of maternal and infant health. We have made tremendous progress toward achieving some of our most ambitious goals, but our work is nowhere near finished:

- More than 24,000 infants still die before their first birthday, particularly those born too early.

- Too many mothers in the U.S. and abroad still die of pregnancy-related causes that are preventable

- Racial, geographic and socioeconomic disparities that lead to negative maternal and infant health outcomes continue to exist.

DRH’s Future: Preserving Progress and Accelerating Change

What will the next 50 years look like? DRH’s work will build on the legacy of informing our efforts by the best available science and focusing on key issues such as:

Expanding and improving PRAMS

For 30 years, the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) has monitored health behaviors and outcomes associated with pregnancy (such as preterm birth, breast feeding, and tobacco use), informing program and policy. We are improving timeliness of data reporting so our on-the-ground colleagues can move faster to implement program and policy change.

Improving maternal mortality surveillance

At least half of maternal deaths are preventable and we are working to improve the data that will identify opportunities to prevent future deaths, including accounting for severe maternal morbidity.

Working to improve infant health

Preterm birth remains an important challenge. Through the Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (PQCs), we are advancing health outcomes for mothers and babies by identifying health care processes that need improvement and quickly making the necessary changes.

Preventing teen and unintended pregnancies

Nearly half of pregnancies in the U.S. are unintended and that figure is even higher among teens. DRH will continue to develop and evaluate interventions to reduce teen pregnancy.

Building epidemiology and program support to states

Our state, local, and tribal partners are uniquely positioned to tackle their communities’ biggest challenges in improving the health and well-being of women, children, and families. Through the Maternal and Child Health Epidemiology Program (MCHEP), DRH will continue to build local capacity to use and apply sound epidemiologic principles to programs and policies.

- Page last reviewed: July 18, 2017

- Page last updated: July 18, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir