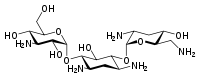

Tobramycin

Tobramycin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic derived from Streptomyces tenebrarius that is used to treat various types of bacterial infections, particularly Gram-negative infections. It is especially effective against species of Pseudomonas.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tobrex, Tobi |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682660 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | IV, IM, inhalation, ophthalmic |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | < 30% |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.046.642 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H37N5O9 |

| Molar mass | 467.515 g/mol g·mol−1 |

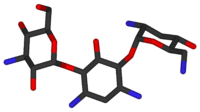

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

It was patented in 1965 and approved for medical use in 1974.[2]

Medical uses

Like all aminoglycosides, tobramycin does not pass the gastro-intestinal tract, so for systemic use it can only be given intravenously or by injection into a muscle. Ophthalmic (tobramycin only, Tobrex, or combined with dexamethasone, sold as TobraDex) and nebulised formulations both have low systemic absorption. The formulation for injection is branded Nebcin. The nebulised formulation (brand name Tobi) is indicated in the treatment of exacerbations of chronic infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients diagnosed with cystic fibrosis. A proprietary formulation of micronized, nebulized tobramycin has been tested as a treatment for bacterial sinusitis.[3] Tobrex is a 0.3% tobramycin sterile ophthalmic solution is produced by Bausch & Lomb Pharmaceuticals. Benzalkonium chloride 0.01% is added as a preservative. It is available by prescription only in the United States and Canada. In certain countries, it is available over the counter. Tobrex and TobraDex are indicated in the treatment of superficial infections of the eye, such as bacterial conjunctivitis. Tobramycin (injection) is also indicated for various severe or life-threatening gram-negative infections: meningitis in neonates, brucellosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, Yersinia pestis infection (plague). Tobramycin is preferred over gentamicin for Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia due to better lung penetration..

Spectrum of susceptibility

Tobramycin has a narrow spectrum of activity and is active against Gram-negative bacteria. Clinically, tobramycin is frequently used to eliminate Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis patients. The following represents MIC susceptibility data for a few strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa:

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa - <0.25 µg/mL - 92 µg/mL [ref?]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa (non-mucoid) - 0.5 µg/mL - >512 µg/mL [ref?]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) - 0.5 µg/mL - 2 µg/mL[4]

The MIC for Klebsiella pneumoniae, KP-1, is 2.3±0.2 µg/mL at 25 °C [unpublished].

Side effects

Like other aminoglycosides, tobramycin is ototoxic:[5] it can cause hearing loss, or a loss of equilibrioception, or both in genetically susceptible individuals. These individuals carry a normally harmless genetic mutation that allows aminoglycosides such as tobramycin to affect cochlear cells. Aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity is generally irreversible.

As with all aminoglycosides, tobramycin is also nephrotoxic, it can damage or destroy the tissue of the kidneys. This effect can be particularly worrisome when multiple doses accumulate over the course of a treatment[6] or when the kidney concentrates urine by increasing tubular reabsorption during sleep. Adequate hydration may help prevent excess nephrotoxicity and subsequent loss of renal function. For these reasons parenteral tobramycin needs to be carefully dosed by body weight, and its serum concentration monitored. Tobramycin is thus said to be a drug with a narrow therapeutic index.

Mechanism of action

Tobramycin works by binding to a site on the bacterial 30S and 50S ribosome, preventing formation of the 70S complex.[7] As a result, mRNA cannot be translated into protein, and cell death ensues.[8] Tobramycin also binds to RNA-aptamers,[9] artificially created molecules to bind to certain targets. However, there seems to be no indication that Tobramycin binds to natural RNAs or other nucleic acids.

The effect of tobramycin can be inhibited by metabolites of the Krebs (TCA) cycle, such as glyoxylate. These metabolites protect against tobramycin lethality by diverting carbon flux away from the TCA cycle, collapsing cellular respiration, and thereby inhibiting Tobramycin uptake and thus lethality.[10]

References

- "Tobramycin" (PDF). Toku-E. 2010-01-12. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 507. ISBN 9783527607495.

- "Nebulized Tobramycin in treating bacterial Sinusitis" (Press release). July 22, 2008. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- http://www.toku-e.com/Assets/MIC/Tobramycin.pdf%5B%5D

- Lerner, A.Martin; Cone, LawrenceA; Jansen, Winfried; Reyes, MilagrosP; Blair, DonaldC; Wright, GraceE; Lorber, RichardR (May 1983). "Randomised, controlled trial of the comparative efficacy, auditory toxicity, and nephrotoxicity of tobramycin and netilmicin". The Lancet. 321 (8334): 1123–1126. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92864-7. PMID 6133153.

- Pedersen, S S; Jensen, T; Osterhammel, D; Osterhammel, P (1 April 1987). "Cumulative and acute toxicity of repeated high-dose tobramycin treatment in cystic fibrosis". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 31 (4): 594–599. doi:10.1128/AAC.31.4.594. PMC 174783. PMID 3606063.

- Yang, Grace; Trylska, Joanna; Tor, Yitzhak; McCammon, J. Andrew (September 2006). "Binding of Aminoglycosidic Antibiotics to the Oligonucleotide A-Site Model and 30S Ribosomal Subunit: Poisson−Boltzmann Model, Thermal Denaturation, and Fluorescence Studies". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 49 (18): 5478–5490. doi:10.1021/jm060288o. PMID 16942021.

- Haddad, Jalal; Kotra, Lakshmi P.; Llano-Sotelo, Beatriz; Kim, Choonkeun; Azucena, Eduardo F.; Liu, Meizheng; Vakulenko, Sergei B.; Chow, Christine S.; Mobashery, Shahriar (April 2002). "Design of Novel Antibiotics that Bind to the Ribosomal Acyltransfer Site". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 124 (13): 3229–3237. doi:10.1021/ja011695m. PMID 11916405.

- Kotra, L. P.; Haddad, J.; Mobashery, S. (1 December 2000). "Aminoglycosides: Perspectives on Mechanisms of Action and Resistance and Strategies to Counter Resistance". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 44 (12): 3249–3256. doi:10.1128/aac.44.12.3249-3256.2000. PMC 90188. PMID 11083623.

- Meylan, Sylvain; Porter, Caroline B.M.; Yang, Jason H.; Belenky, Peter; Gutierrez, Arnaud; Lobritz, Michael A.; Park, Jihye; Kim, Sun H.; Moskowitz, Samuel M.; Collins, James J. (February 2017). "Carbon Sources Tune Antibiotic Susceptibility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa via Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Control". Cell Chemical Biology. 24 (2): 195–206. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.12.015. PMC 5426816.

Further reading

- Davis, B. D. (1 September 1987). "Mechanism of bactericidal action of aminoglycosides". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 51 (3): 341–350. PMC 373115. PMID 3312985.

External links

- Tobramycin bound to proteins in the Protein Data Bank