Hormone

A hormone (from the Greek participle ὁρμῶν, "setting in motion") is any member of a class of signaling molecules, produced by glands in multicellular organisms, that are transported by the circulatory system to target distant organs to regulate physiology and behavior.[1] Hormones have diverse chemical structures, mainly of three classes:

- eicosanoids

- steroids

- amino acid/protein derivatives (amines, peptides, and proteins)

The glands that secrete hormones comprise the endocrine signaling system. The term "hormone" is sometimes extended to include chemicals produced by cells that affect the same cell (autocrine or intracrine signaling) or nearby cells (paracrine signalling).

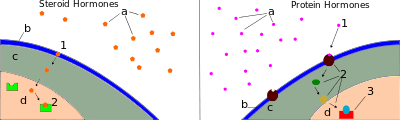

Hormones serve to communicate between organs and tissues for physiological regulation and behavioral activities such as digestion, metabolism, respiration, tissue function, sensory perception, sleep, excretion, lactation, stress induction, growth and development, movement, reproduction, and mood manipulation.[2][3] Hormones affect distant cells by binding to specific receptor proteins in the target cell, resulting in a change in cell function. When a hormone binds to the receptor, it results in the activation of a signal transduction pathway that typically activates gene transcription, resulting in increased expression of target proteins; non-genomic effects are more rapid, and can be synergistic with genomic effects.[4] Amino acid–based hormones (amines and peptide or protein hormones) are water-soluble and act on the surface of target cells via second messengers; steroid hormones, being lipid-soluble, move through the plasma membranes of target cells (both cytoplasmic and nuclear) to act within their nuclei.

Hormone secretion may occur in many tissues. Endocrine glands provide the cardinal example, but specialized cells in various other organs also secrete hormones. Hormone secretion occurs in response to specific biochemical signals from a wide range of regulatory systems. For instance, serum calcium concentration affects parathyroid hormone synthesis; blood sugar (serum glucose concentration) affects insulin synthesis; and because the outputs of the stomach and exocrine pancreas (the amounts of gastric juice and pancreatic juice) become the input of the small intestine, the small intestine secretes hormones to stimulate or inhibit the stomach and pancreas based on how busy it is. Regulation of hormone synthesis of gonadal hormones, adrenocortical hormones, and thyroid hormones often depends on complex sets of direct-influence and feedback interactions involving the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA), -gonadal (HPG), and -thyroid (HPT) axes.

Upon secretion, certain hormones, including protein hormones and catecholamines, are water-soluble and are thus readily transported through the circulatory system. Other hormones, including steroid and thyroid hormones, are lipid-soluble; to achieve widespread distribution, these hormones must bond to carrier plasma glycoproteins (e.g., thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG)) to form ligand-protein complexes. Some hormones are completely active when released into the bloodstream (as is the case for insulin and growth hormones), while others are prohormones that must be activated in specific cells through a series of activation steps that are commonly highly regulated. The endocrine system secretes hormones directly into the bloodstream, typically via fenestrated capillaries, whereas the exocrine system secretes its hormones indirectly using ducts. Hormones with paracrine function diffuse through the interstitial spaces to nearby target tissue.

Introduction and overview

Hormonal signaling involves the following steps:[5]

- Biosynthesis of a particular hormone in a particular tissue

- Storage and secretion of the hormone

- Transport of the hormone to the target cell(s)

- Recognition of the hormone by an associated cell membrane or intracellular receptor protein

- Relay and amplification of the received hormonal signal via a signal transduction process: This then leads to a cellular response. The reaction of the target cells may then be recognized by the original hormone-producing cells, leading to a downregulation in hormone production. This is an example of a homeostatic negative feedback loop.

- Breakdown of the hormone.

Hormone producing cells are typically of a specialized cell type, residing within a particular endocrine gland, such as the thyroid gland, ovaries, and testes. Hormones exit their cell of origin via exocytosis or another means of membrane transport. The hierarchical model is an oversimplification of the hormonal signaling process. Cellular recipients of a particular hormonal signal may be one of several cell types that reside within a number of different tissues, as is the case for insulin, which triggers a diverse range of systemic physiological effects. Different tissue types may also respond differently to the same hormonal signal.

Discovery

The discovery of hormones and endocrine signaling occurred during studies of how the digestive system regulates its activities, as explained at Secretin § Discovery.

Arnold Adolph Berthold (1849)

Arnold Adolph Berthold was a German physiologist and zoologist, who, in 1849, had a question about the function of the testes. He noticed that in castrated roosters that they did not have the same sexual behaviors as roosters with their testes intact. He decided to run an experiment on male roosters to examine this phenomenon. He kept a group of roosters with their testes intact, and saw that they had normal sized wattles and combs (secondary sexual organs), a normal crow, and normal sexual and aggressive behaviors. He also had a group with their testes surgically removed, and noticed that their secondary sexual organs were decreased in size, had a weak crow, did not have sexual attraction towards females, and were not aggressive. He realized that this organ was essential for these behaviors, but he did not know how. To test this further, he removed one testis and placed it in the abdominal cavity. The roosters acted and had normal physical anatomy. He was able to see that location of the testes do not matter. He then wanted to see if it was a genetic factor that was involved in the testes that provided these functions. He transplanted a testis from another rooster to a rooster with one testis removed, and saw that they had normal behavior and physical anatomy as well. Berthold determined that the location or genetic factors of the testes do not matter in relation to sexual organs and behaviors, but that some chemical in the testes being secreted is causing this phenomenon. It was later identified that this factor was the hormone testosterone.[6][7]

Bayliss and Starling (1902)

William Bayliss and Ernest Starling, a physiologist and biologist, respectively, wanted to see if the nervous system had an impact on the digestive system. They knew that the pancreas was involved in the secretion of digestive fluids after the passage of food from the stomach to the intestines, which they believed to be due to the nervous system. They cut the nerves to the pancreas in an animal model and discovered that it was not nerve impulses that controlled secretion from the pancreas. It was determined that a factor secreted from the intestines into the bloodstream was stimulating the pancreas to secrete digestive fluids. This factor was named secretin: a hormone, although the term hormone was not coined until 1905 by Starling.[8]

Types of signaling

Hormonal effects are dependent on where they are released, as they can be released in different manners.[9] Not all hormones are released from a cell and into the blood until it binds to a receptor on a target. The major types of hormone signaling are:

- Endocrine – Acts on the target cell after being released into the bloodstream.

- Paracrine – Acts on a nearby cell and does not have to enter general circulation.

- Autocrine – Affects the cell type that secreted it and causes a biological effect.

- Intracrine – Acts intracellularly on the cell that synthesized it.

Chemical classes

As hormones are defined functionally, not structurally, they may have diverse chemical structures. Hormones occur in multicellular organisms (plants, animals, fungi, brown algae, and red algae). These compounds occur also in unicellular organisms, and may act as signaling molecules however there is no agreement that these molecules can be called hormones.[10][11]

Vertebrate

- Peptide

- Peptide hormones are made of a chain of amino acids that can range from just 3 to hundreds of amino acids. Examples include oxytocin and insulin.[12] Their sequences are encoded in DNA and can be modified by alternative splicing and/or post-translational modification.[9] They are packed in vesicles and are hydrophilic, meaning that they are soluble in water. Due to their hydrophilicity, they can only bind to receptors on the membrane, as travelling through the membrane is unlikely. However, some hormones can bind to intracellular receptors through an intracrine mechanism.

- Amino acid

- Amino acid hormones are derived from amino acid, most commonly tyrosine. They are hydrophilic and act on membrane receptors. They are stored in vesicles. Examples include melatonin and thyroxine.

- Eicosanoid

- Eicosanoids hormones are derived from lipids such as arachidonic acid, lipoxins and prostaglandins. Examples include prostaglandin and thromboxane. These hormones are produced by cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases. They are hydrophobic and act on membrane receptors.

- Steroid

- Steroid hormones are derived from cholesterol. Examples include the sex hormones estradiol and testosterone as well as the stress hormone cortisol.[13] Steroid contain four fused rings. They are lipophilic and hence can cross membranes to bind to intracellular nuclear receptors.

Invertebrate

Compared with vertebrates, insects and crustaceans possess a number of structurally unusual hormones such as the juvenile hormone, a sesquiterpenoid.[14]

Plant

Examples include abscisic acid, auxin, cytokinin, ethylene, and gibberellin.[15]

Receptors

Most hormones initiate a cellular response by initially binding to either cell membrane associated or intracellular receptors. A cell may have several different receptor types that recognize the same hormone but activate different signal transduction pathways, or a cell may have several different receptors that recognize different hormones and activate the same biochemical pathway.[16]

Receptors for most peptide as well as many eicosanoid hormones are embedded in the plasma membrane at the surface of the cell and the majority of these receptors belong to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) class of seven alpha helix transmembrane proteins. The interaction of hormone and receptor typically triggers a cascade of secondary effects within the cytoplasm of the cell, described as signal transduction, often involving phosphorylation or dephosphorylation of various other cytoplasmic proteins, changes in ion channel permeability, or increased concentrations of intracellular molecules that may act as secondary messengers (e.g., cyclic AMP). Some protein hormones also interact with intracellular receptors located in the cytoplasm or nucleus by an intracrine mechanism.[17][18]

For steroid or thyroid hormones, their receptors are located inside the cell within the cytoplasm of the target cell. These receptors belong to the nuclear receptor family of ligand-activated transcription factors. To bind their receptors, these hormones must first cross the cell membrane. They can do so because they are lipid-soluble. The combined hormone-receptor complex then moves across the nuclear membrane into the nucleus of the cell, where it binds to specific DNA sequences, regulating the expression of certain genes, and thereby increasing the levels of the proteins encoded by these genes.[19] However, it has been shown that not all steroid receptors are located inside the cell. Some are associated with the plasma membrane.[20]

Effects

Hormones have the following effects on the body:[21]

- stimulation or inhibition of growth

- wake-sleep cycle and other circadian rhythms

- mood swings

- induction or suppression of apoptosis (programmed cell death)

- activation or inhibition of the immune system

- regulation of metabolism

- preparation of the body for mating, fighting, fleeing, and other activity

- preparation of the body for a new phase of life, such as puberty, parenting, and menopause

- control of the reproductive cycle

- hunger cravings

A hormone may also regulate the production and release of other hormones. Hormone signals control the internal environment of the body through homeostasis.

Regulation

The rate of hormone biosynthesis and secretion is often regulated by a homeostatic negative feedback control mechanism. Such a mechanism depends on factors that influence the metabolism and excretion of hormones. Thus, higher hormone concentration alone cannot trigger the negative feedback mechanism. Negative feedback must be triggered by overproduction of an "effect" of the hormone.[22][23]

Hormone secretion can be stimulated and inhibited by:

- Other hormones (stimulating- or releasing -hormones)

- Plasma concentrations of ions or nutrients, as well as binding globulins

- Neurons and mental activity

- Environmental changes, e.g., of light or temperature

One special group of hormones is the tropic hormones that stimulate the hormone production of other endocrine glands. For example, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) causes growth and increased activity of another endocrine gland, the thyroid, which increases output of thyroid hormones.[24][24]

To release active hormones quickly into the circulation, hormone biosynthetic cells may produce and store biologically inactive hormones in the form of pre- or prohormones. These can then be quickly converted into their active hormone form in response to a particular stimulus.[24][24]

Eicosanoids are considered to act as local hormones. They are considered to be "local" because they possess specific effects on target cells close to their site of formation. They also have a rapid degradation cycle, making sure they do not reach distant sites within the body.[25]

Hormones are also regulated by receptor agonists. Hormones are ligands, which are any kinds of molecules that produce a signal by binding to a receptor site on a protein. Hormone effects can be inhibited, thus regulated, by competing ligands that bind to the same target receptor as the hormone in question. When a competing ligand is bound to the receptor site, the hormone is unable to bind to that site and is unable to elicit a response from the target cell. These competing ligands are called antagonists of the hormone.[26]

Therapeutic use

Many hormones and their structural and functional analogs are used as medication. The most commonly prescribed hormones are estrogens and progestogens (as methods of hormonal contraception and as HRT),[27] thyroxine (as levothyroxine, for hypothyroidism) and steroids (for autoimmune diseases and several respiratory disorders). Insulin is used by many diabetics. Local preparations for use in otolaryngology often contain pharmacologic equivalents of adrenaline, while steroid and vitamin D creams are used extensively in dermatological practice.

A "pharmacologic dose" or "supraphysiological dose" of a hormone is a medical usage referring to an amount of a hormone far greater than naturally occurs in a healthy body. The effects of pharmacologic doses of hormones may be different from responses to naturally occurring amounts and may be therapeutically useful, though not without potentially adverse side effects. An example is the ability of pharmacologic doses of glucocorticoids to suppress inflammation.

Hormone-behavior interactions

At the neurological level, behavior can be inferred based on: hormone concentrations; hormone-release patterns; the numbers and locations of hormone receptors; and the efficiency of hormone receptors for those involved in gene transcription. Not only do hormones influence behavior, but also behavior and the environment influence hormones. Thus, a feedback loop is formed. For example, behavior can affect hormones, which in turn can affect behavior, which in turn can affect hormones, and so on.[28]

Three broad stages of reasoning may be used when determining hormone-behavior interactions:

- The frequency of occurrence of a hormonally dependent behavior should correspond to that of its hormonal source

- A hormonally dependent behavior is not expected if the hormonal source (or its types of action) is non-existent

- The reintroduction of a missing behaviorally dependent hormonal source (or its types of action) is expected to bring back the absent behavior

Comparison with neurotransmitters

There are various clear distinctions between hormones and neurotransmitters:[29][30][26]

- A hormone can perform functions over a larger spatial and temporal scale than can a neurotransmitter.

- Hormonal signals can travel virtually anywhere in the circulatory system, whereas neural signals are restricted to pre-existing nerve tracts

- Assuming the travel distance is equivalent, neural signals can be transmitted much more quickly (in the range of milliseconds) than can hormonal signals (in the range of seconds, minutes, or hours). Neural signals can be sent at speeds up to 100 meters per second.[31]

- Neural signalling is an all-or-nothing (digital) action, whereas hormonal signalling is an action that can be continuously variable as dependent upon hormone concentration.

Neurohormones are a type of hormone that are produced by endocrine cells that receive input from neurons, or neuroendocrine cells.[32] Both classic hormones and neurohormones are secreted by endocrine tissue; however, neurohormones are the result of a combination between endocrine reflexes and neural reflexes, creating a neuroendocrine pathway.[26] While endocrine pathways produce chemical signals in the form of hormones, the neuroendocrine pathway involves the electrical signals of neurons.[26] In this pathway, the result of the electrical signal produced by a neuron is the release of a chemical, which is the neurohormone.[26] Finally, like a classic hormone, the neurohormone is released into the bloodstream to reach its target.[26]

Binding proteins

Hormone transport and the involvement of binding proteins is an essential aspect when considering the function of hormones. There are several benefits with the formation of a complex with a binding protein: the effective half-life of the bound hormone is increased; a reservoir of bound hormones is created, which evens the variations in concentration of unbound hormones (bound hormones will replace the unbound hormones when these are eliminated).[33]

See also

- Autocrine signaling

- Cytokine

- Endocrine disruptor

- Endocrine system

- Endocrinology

- Environmental hormones

- Growth factor

- Intracrine

- List of investigational hormonal agents

- Metabolomics

- Neuroendocrinology

- Paracrine signaling

- Plant hormones, a.k.a. plant growth regulators

- Semiochemical

- Sex-hormonal agent

- Sexual motivation and hormones

- Xenohormone

References

- Shuster, Michèle,. Biology for a changing world, with physiology (Second edition ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9781464151132. OCLC 884499940.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- Neave N (2008). Hormones and behaviour: a psychological approach. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0521692014. Lay summary – Project Muse.

- "Hormones". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Ruhs S, Nolze A, Hübschmann R, Grossmann C (July 2017). "30 Years of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor: Nongenomic effects via the mineralocorticoid receptor". The Journal of Endocrinology. 234 (1): T107–T124. doi:10.1530/JOE-16-0659. PMID 28348113.

- Nussey S, Whitehead S (2001). Endocrinology: an integrated approach. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publ. ISBN 978-1-85996-252-7.

- Belfiore A, LeRoith (eds.). Principles of endocrinology and hormone action. Cham. ISBN 9783319446752. OCLC 1021173479.

- Molina PE, ed. (2018). Endocrine physiology. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9781260019353. OCLC 1034587285.

- Bayliss WM, Starling EH (1968). "The Mechanism of Pancreatic Secretion". In Leicester HM (ed.). Source Book in Chemistry, 1900–1950. Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674366701.c111. ISBN 9780674366701.

- Molina PE (2018). Endocrine physiology. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9781260019353. OCLC 1034587285.

- Lenard J (April 1992). "Mammalian hormones in microbial cells". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 17 (4): 147–50. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(92)90323-2. PMID 1585458.

- Janssens PM (1987). "Did vertebrate signal transduction mechanisms originate in eukaryotic microbes?". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 12: 456–459. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(87)90223-4.

- Principles of endocrinology and hormone action. Belfiore, Antonino,, LeRoith, Derek, 1945-. Cham. ISBN 9783319446752. OCLC 1021173479.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Marieb E (2014). Anatomy & physiology. Glenview, IL: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 978-0321861580.

- Heyland A, Hodin J, Reitzel AM (January 2005). "Hormone signaling in evolution and development: a non-model system approach". BioEssays. 27 (1): 64–75. doi:10.1002/bies.20136. PMID 15612033.

- Wang, Yu Hua; Irving, Helen R (April 2011). "Developing a model of plant hormone interactions". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 6 (4): 494–500. doi:10.4161/psb.6.4.14558. ISSN 1559-2316. PMC 3142376. PMID 21406974.

- "Signal relay pathways". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- Lodish, Harvey; Berk, Arnold; Zipursky, S. Lawrence; Matsudaira, Paul; Baltimore, David; Darnell, James (2000). "G Protein –Coupled Receptors and Their Effectors". Molecular Cell Biology. 4th edition.

- Rosenbaum, Daniel M.; Rasmussen, Søren G. F.; Kobilka, Brian K. (2009-05-21). "The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors". Nature. 459 (7245): 356–363. doi:10.1038/nature08144. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 3967846. PMID 19458711.

- Beato M, Chávez S, Truss M (April 1996). "Transcriptional regulation by steroid hormones". Steroids. 61 (4): 240–51. doi:10.1016/0039-128X(96)00030-X. PMID 8733009.

- Hammes SR (March 2003). "The further redefining of steroid-mediated signaling". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (5): 2168–70. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.2168H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0530224100. PMC 151311. PMID 12606724.

- Lall, Solomon (2013). Clearopathy. India: Partridge Publishing India. p. 1. ISBN 9781482815887.

- Campbell, Miles; Jialal, Ishwarlal (2019), "Physiology, Endocrine Hormones", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30860733, retrieved 2019-11-13

- Röder, Pia V; Wu, Bingbing; Liu, Yixian; Han, Weiping (March 2016). "Pancreatic regulation of glucose homeostasis". Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 48 (3): e219. doi:10.1038/emm.2016.6. ISSN 1226-3613. PMC 4892884. PMID 26964835.

- Shah, Shilpa Bhupatrai. (2012). Allergy-hormone links. Saxena, Richa. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd. ISBN 9789350250136. OCLC 761377585.

- "Eicosanoids". www.rpi.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- Silverthorn, Dee Unglaub, 1948-. Human physiology : an integrated approach. Johnson, Bruce R., Ober, William C., Ober, Claire E., Silverthorn, Andrew C. (Seventh edition ed.). [San Francisco]. ISBN 9780321981226. OCLC 890107246.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- "Hormone Therapy". Cleveland Clinic.

- Garland, Theodore; Zhao, Meng; Saltzman, Wendy (August 2016). "Hormones and the Evolution of Complex Traits: Insights from Artificial Selection on Behavior". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 56 (2): 207–224. doi:10.1093/icb/icw040. ISSN 1540-7063. PMC 5964798. PMID 27252193.

- Reece, Jane B. Campbell biology. Urry, Lisa A., Cain, Michael L. (Michael Lee), 1956-, Wasserman, Steven Alexander, Minorsky, Peter V., Jackson, Robert B., Campbell, Neil A., 1946-2004. (Tenth edition ed.). Boston. ISBN 9780321775658. OCLC 849822337.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- Siegel, Allan, 1939- (2006). Essential neuroscience. Sapru, Hreday N., Siegel, Heidi. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0781750776. OCLC 60650938.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Alberts, Bruce, (2002). Molecular biology of the cell. Johnson, Alexander,, Lewis, Julian,, Raff, Martin,, Roberts, Keith,, Walter, Peter, (4th ed ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0815332181. OCLC 48122761.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- Life, the science of biology. Purves, William K. (William Kirkwood), 1934- (6th ed ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. 2001. ISBN 0716738732. OCLC 45064683.CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- Boron WF, Boulpaep EL. Medical physiology: a cellular and molecular approach. Updated 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2012.

External links

- HMRbase: A database of hormones and their receptors

- Hormones at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)