Endocrine gland

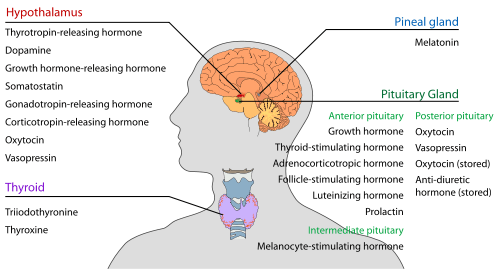

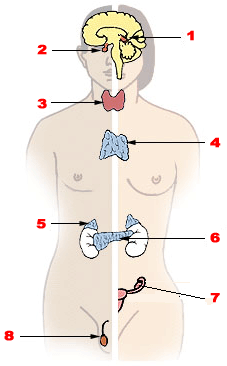

Endocrine glands are ductless glands of the endocrine system that secrete their products, hormones, directly into the blood. The major glands of the endocrine system include the pineal gland, pituitary gland, pancreas, ovaries, testes, thyroid gland, parathyroid gland, hypothalamus and adrenal glands. The hypothalamus and pituitary gland are neuroendocrine organs.

| Endocrine glands | |

|---|---|

The major endocrine glands:

1 Pineal gland 2 Pituitary gland 3 Thyroid gland 4 Thymus 5 Adrenal gland 6 Pancreas 7 Ovary (female) 8 Testis (male) | |

| Details | |

| System | Endocrine system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | glandulae endocrinae |

| MeSH | D004702 |

| TA | A11.0.00.000 |

| TH | H2.00.02.0.03072 |

| FMA | 9602 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The pituitary gland hangs from the base of the brain by the pituitary stalk, and is enclosed by bone. It consists of a hormone-producing glandular portion the anterior pituitary and a neural portion the posterior pituitary, which is an extension of the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus regulates the hormonal output of the anterior pituitary and creates two hormones that it exports to the posterior pituitary for storage and later release.

Four of the six anterior pituitary hormones are tropic hormones that regulate the function of other endocrine organs. Most anterior pituitary hormones exhibit a diurnal rhythm of release, which is subject to modification by stimuli influencing the hypothalamus.

Somatotropic hormone or growth hormone (GH) is an anabolic hormone that stimulates growth of all body tissues especially skeletal muscle and bone. It may act directly, or indirectly via insulin-like growth factors (IGFs). GH mobilizes fats, stimulates protein synthesis, and inhibits glucose uptake and metabolism. Secretion is regulated by growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH) and growth hormone inhibiting hormone (GHIH), or somatostatin. Hypersecretion causes gigantism in children and acromegaly in adults; hyposecretion in children causes pituitary dwarfism.

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) promotes normal development and activity of the thyroid gland. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulates its release; negative feedback of thyroid hormone inhibits it.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulates the adrenal cortex to release corticosteroids. ACTH release is triggered by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and inhibited by rising glucocorticoid levels.

The gonadotropins—follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) regulate the functions of the gonads in both sexes. FSH stimulates sex cell production; LH stimulates gonadal hormone production. Gonadotropin levels rise in response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). Negative feedback of gonadal hormones inhibits gonadotropin release.

Prolactin (PRL) promotes milk production in human females. Its secretion is prompted by prolactin-releasing hormone (PRH) and inhibited by prolactin-inhibiting hormone (PIH).

The intermediate lobe of pituitary gland secretes only one enzyme that is melanocyte stimulating hormone(MSH). It is linked with the formation of the black pigment in our skin called melanin.

The neurohypophysis stores and releases two hypothalamic hormones:

- Oxytocin stimulates powerful uterine contractions, which trigger labor and delivery of an infant, and milk ejection in nursing women. Its release is mediated reflexively by the hypothalamus and represents a positive feedback mechanism.

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) stimulates the kidney tubules to reabsorb and conserve water, resulting in small volumes of highly concentrated urine and decreased plasma osmolarity. ADH is released in response to high solute concentrations in the blood and inhibited by low solute concentrations in the blood. Hyposecretion results in diabetes insipidus.

Development

Endocrine glands derive from all three germ layers.

The natural decrease in function of the female’s ovaries during late middle age results in menopause. The efficiency of all endocrine glands seems to decrease gradually as aging occurs. This leads to a generalized increase in the incidence of diabetes mellitus and a lower metabolic rate.

Function

Hormones

Local chemical messengers, not generally considered part of the endocrine system, include autocrines, which act on the cells that secrete them, and paracrines, which act on a different cell type nearby.

The ability of a target cell to respond to a hormone depends on the presence of receptors, within the cell or on its plasma membrane, to which the hormone can bind.

Hormone receptors are dynamic structures. Changes in number and sensitivity of hormone receptors may occur in response to high or low levels of stimulating hormones.

Blood levels of hormones reflect a balance between secretion and degradation/excretion. The liver and kidneys are the major organs that degrade hormones; breakdown products are excreted in urine and feces.

Hormone half-life and duration of activity are limited and vary from hormone to hormone.

Interaction of hormones at target cells Permissiveness is the situation in which a hormone cannot exert its full effects without the presence of another hormone.

Synergism occurs when two or more hormones produce the same effects in a target cell and their results are amplified.

Antagonism occurs when a hormone opposes or reverses the effect of another hormone.

Control

The endocrine glands belong to the body's control system. The hormones which they produce help to regulate the functions of cells and tissues throughout the body. Endocrine organs are activated to release their hormones by humoral, neural or hormonal stimuli. Negative feedback is important in regulating hormone levels in the blood.

The nervous system, acting through hypothalamic controls, can in certain cases override or modulate hormonal effects.

Clinical significance

Disease

Diseases of the endocrine glands are common,[4] including conditions such as diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, and obesity.

Endocrine disease is characterized by irregulated hormone release (a productive pituitary adenoma), inappropriate response to signaling (hypothyroidism), lack of a gland (diabetes mellitus type 1, diminished erythropoiesis in chronic renal failure), or structural enlargement in a critical site such as the thyroid (toxic multinodular goitre). Hypofunction of endocrine glands can occur as a result of loss of reserve, hyposecretion, agenesis, atrophy, or active destruction. Hyperfunction can occur as a result of hypersecretion, loss of suppression, hyperplastic or neoplastic change, or hyperstimulation.

Endocrinopathies are classified as primary, secondary, or tertiary. Primary endocrine disease inhibits the action of downstream glands. Secondary endocrine disease is indicative of a problem with the pituitary gland. Tertiary endocrine disease is associated with dysfunction of the hypothalamus and its releasing hormones.

As the thyroid, and hormones have been implicated in signaling distant tissues to proliferate, for example, the estrogen receptor has been shown to be involved in certain breast cancers. Endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine signaling have all been implicated in proliferation, one of the required steps of oncogenesis.[5]

Other common diseases that result from endocrine dysfunction include Addison’s disease, Cushing’s disease and Grave’s disease. Cushing's disease and Addison's disease are pathologies involving the dysfunction of the adrenal gland. Dysfunction in the adrenal gland could be due to primary or secondary factors and can result in hypercortisolism or hypocortisolism . Cushing’s disease is characterized by the hypersecretion of the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) due to a pituitary adenoma that ultimately causes endogenous hypercortisolism by stimulating the adrenal glands.[6] Some clinical signs of Cushing’s disease include obesity, moon face, and hirsutism.[7] Addison's disease is an endocrine disease that results from hypocortisolism caused by adrenal gland insufficiency. Adrenal insufficiency is significant because it is correlated with decreased ability to maintain blood pressure and blood sugar, a defect that can prove to be fatal.[8]

Graves' disease involves the hyperactivity of the thyroid gland which produces the T3 and T4 hormones.[7] Graves' disease effects range from excess sweating, fatigue, heat intolerance and high blood pressure to swelling of the eyes that causes redness, puffiness and in rare cases reduced or double vision.

Graves' disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism; hyposecretion causes cretinism in infants and myxoedema in adults.

Hyperparathyroidism results in hypercalcaemia and its effects and in extreme bone wasting. Hypoparathyroidism leads to hypocalcaemia, evidenced by tetany seizure and respiratory paralysis. Hyposecretion of insulin results in diabetes mellitus; cardinal signs are polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia.

References

- Endocrinology: Tissue Histology. Archived 2010-02-04 at the Wayback Machine University of Nebraska at Omaha.

- "Adrenal gland". Medline Plus/Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002.

- Kasper (2005). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. McGraw Hill. p. 2074. ISBN 978-0-07-139140-5.

- Bhowmick NA, Chytil A, Plieth D, Gorska AE, Dumont N, Shappell S, Washington MK, Neilson EG, Moses HL (2004). "TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia". Science. 303 (5659): 848–51. doi:10.1126/science.1090922. PMID 14764882.

- Buliman A, Tataranu LG, Paun DL, Mirica A, Dumitrache C (2016). "Cushing's disease: a multidisciplinary overview of the clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment". Journal of Medicine & Life. 9 (1): 12–18.

- Vander, Arthur (2008). Vander's Human Physiology: the mechanisms of body function. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. pp. 345-347

- Inder, Warrick J.; Meyer, Caroline; Hunt, Penny J. (2015-06-01). "Management of hypertension and heart failure in patients with Addison's disease". Clinical Endocrinology. 82 (6): 789–792. doi:10.1111/cen.12592. ISSN 1365-2265. PMID 25138826.