Levothyroxine

Levothyroxine, also known as L-thyroxine, is a manufactured form of the thyroid hormone thyroxine (T4).[1][4] It is used to treat thyroid hormone deficiency, including the severe form known as myxedema coma.[1] It may also be used to treat and prevent certain types of thyroid tumors.[1] It is not indicated for weight loss.[1] Levothyroxine is taken by mouth or given by injection into a vein.[1] Maximum effect from a specific dose can take up to six weeks to occur.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

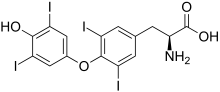

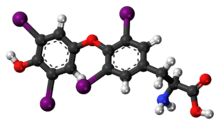

| Other names | 3,5,3′,5′-Tetraiodo-L-thyronine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682461 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | by mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 40-80%[1] |

| Metabolism | mainly in liver, kidneys, brain and muscles |

| Elimination half-life | ca. 7 days (in hyperthyroidism 3–4 days, in hypothyroidism 9–10 days) |

| Excretion | feces and urine |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.093 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H11I4NO4 |

| Molar mass | 776.874 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 231 to 233 °C (448 to 451 °F) [2] |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble (0.105 mg·mL−1 at 25 °C)[3] mg/mL (20 °C) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Side effects from excessive doses include weight loss, trouble tolerating heat, sweating, anxiety, trouble sleeping, tremor, and fast heart rate.[1] Use is not recommended in people who have had a recent heart attack.[1] Use during pregnancy has been found to be safe.[1] It is recommended that dosing be based on regular measurements of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and T4 levels in the blood.[1] Much of the effect of levothyroxine is following its conversion to triiodothyronine (T3).[1]

Levothyroxine was first made in 1927.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, which lists the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[5] Levothyroxine is available as a generic medication.[1] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.58 to US$12.28 per month.[6] In the United States, a typical month of treatment costs less than US$25.[7] Levothyroxine was the most commonly prescribed medication in the United States as of 2016, with more than 114 million prescriptions.[8]

Medical use

Levothyroxine is typically used to treat hypothyroidism,[9] and is the treatment of choice for people with hypothyroidism,[10] who often require lifelong thyroid hormone therapy.[11] Doses of levothyroxine that normalize serum TSH may not normalize LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol.[12]

It may also be used to treat goiter via its ability to lower thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), a hormone that is considered goiter-inducing.[13][14] Levothyroxine is also used as interventional therapy in people with nodular thyroid disease or thyroid cancer to suppress thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secretion.[15] A subset of people with hypothyroidism treated with an appropriate dose of levothyroxine will describe continuing symptoms despite TSH levels in the normal range.[11] In these people, further laboratory and clinical evaluation is warranted as they may have another cause for their symptoms.[11] Furthermore, it is important to review their medications and possible dietary supplements as several medications can affect thyroid hormone levels.[11]

Levothyroxine is also used to treat subclinical hypothyroidism which is defined by an elevated TSH level and a normal-range free T4 level without symptoms.[11] Such people may be asymptomatic[11] and whether they should be treated is controversial.[10] One benefit of treating this population with levothyroxine therapy is preventing development of hypothyroidism.[10] As such, it is recommended that treatment should be taken into account for patients with initial TSH levels above 10 mIU/L, people with elevated thyroid peroxidase antibody titers, people with symptoms of hypothyroidism and TSH levels between 5–10 mIU/L, and women who are pregnant or want to become pregnant.[10] Oral dosing for patients with subclinical hypothyroidism is 1 μg/kg/day.[16]

It is also used to treat myxedema coma, which is a severe form of hypothyroidism characterized by mental status changes and hypothermia.[11] As it is a medical emergency with a high mortality rate, it should be treated in the intensive care unit[11] with thyroid hormone replacement and aggressive management of individual organ system complications.[10]

Dosages vary according to the age groups and the individual condition of the person, body weight and compliance to the medication and diet. Other predictors of the required dosage are sex, BMI, deiodinase activity (SPINA-GD) and etiology of hypothyroidism.[17] Annual or semiannual clinical evaluations and TSH monitoring are appropriate after dosing has been established.[18] Levothyroxine is taken on an empty stomach approximately half an hour to an hour before meals.[19] As such, thyroid replacement therapy is usually taken 30 minutes prior to eating in the morning.[11] For patients with trouble taking levothyroxine in the morning, bedtime dosing is effective as well.[11] A recent study published in JAMA showed greater efficacy of levothyroxine when taken at bedtime.[20]

Poor compliance in taking the medicine is the most common cause of elevated TSH levels in people receiving appropriate doses of levothyroxine.[11]

Elderly

For older people (over 50 years old) and people with known or suspected ischemic heart disease, levothyroxine therapy should not be initiated at the full replacement dose.[21] Since thyroid hormone increases the heart's oxygen demand by increasing heart rate and contractility, starting at higher doses may cause an acute coronary syndrome or an abnormal heart rhythm.[11]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration pregnancy categories, levothyroxine has been assigned Pregnancy Category A.[21] Given that no increased risk of congenital abnormalities have been demonstrated in pregnant women taking levothyroxine, therapy should be continued during pregnancy.[21] Furthermore, therapy should be immediately administered to women diagnosed with hypothyroidism during pregnancy, as hypothyroidism is associated with a higher rate of complications, such as spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, and premature birth.[21]

Thyroid hormone requirements increase during and last throughout pregnancy.[11] As such, it is recommended that pregnant women increase to nine doses of levothyroxine each week, rather than the usual seven, as soon as their pregnancy is confirmed.[11] Repeat thyroid function tests should be done five weeks after the dosage is increased.[11]

While a minimal amount of thyroid hormones are found in breast milk, the amount does not influence infant plasma thyroid levels.[16] Furthermore, levothyroxine was not found to cause any adverse events to the infant or mother during breastfeeding.[16] As adequate concentrations of thyroid hormone are required to maintain normal lactation, it is recommended that appropriate levothyroxine doses be administered during breastfeeding.[16]

Children

Levothyroxine is safe and effective for children with hypothyroidism; the goal of treatment for children with hypothyroidism is to reach and preserve normal intellectual and physical development.[21]

Contraindications

Levothyroxine is contraindicated in people with hypersensitivity to levothyroxine sodium or any component of the formulation, people with acute myocardial infarction, and people with thyrotoxicosis of any etiology.[16] Levothyroxine is also contraindicated for people with uncorrected adrenal insufficiency, as thyroid hormones may cause an acute adrenal crisis by increasing the metabolic clearance of glucocorticoids.[21] For oral tablets, the inability to swallow capsules serves as an additional contraindication.[16]

Side effects

Adverse events are generally caused by incorrect dosing. Long-term suppression of TSH values below normal values will frequently cause cardiac side-effects and contribute to decreases in bone mineral density (low TSH levels are also well known to contribute to osteoporosis).[22]

Too high a dose of levothyroxine causes hyperthyroidism.[19] Overdose can result in heart palpitations, abdominal pain, nausea, anxiousness, confusion, agitation, insomnia, weight loss, and increased appetite.[23] Allergic reactions to the drug are characterized by symptoms such as difficulty breathing, shortness of breath, or swelling of the face and tongue. Acute overdose may cause fever, hypoglycemia, heart failure, coma, and unrecognized adrenal insufficiency.

Acute massive overdose may be life-threatening; treatment should be symptomatic and supportive. Massive overdose can be associated with increased sympathetic activity and thus require treatment with beta-blockers.[19]

The effects of overdosing appear 6 hours to 11 days after ingestion.[23]

Interactions

There are foods and other substances that can interfere with absorption of thyroxine. Substances that reduce absorption are aluminium and magnesium containing antacids, simethicone, sucralfate, cholestyramine, colestipol, and polystyrene sulfonate. Grapefruit juice may delay the absorption of levothyroxine, but based on a study of 10 healthy people aged 20–30 (8 men, 2 women) it may not have a significant effect on bioavailability in young adults.[24] A study of eight women suggested that coffee may interfere with the intestinal absorption of levothyroxine, though at a level less than eating bran.[25] Certain other substances can cause adverse effects that may be severe. Combination of levothyroxine with ketamine may cause hypertension and tachycardia;[26] and tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants increase its toxicity. On the other hand, lithium can cause hyperthyroidism (but most often hypothyroidism) by affecting iodine metabolism of the thyroid itself and thus inhibits synthetic levothyroxine as well.[27]

Mechanism of action

Levothyroxine is a synthetic form of thyroxine (T4), an endogenous hormone secreted by the thyroid gland, which is converted to its active metabolite, L-triiodothyronine (T3).[21] T4 and T3 bind to thyroid receptor proteins in the cell nucleus and cause metabolic effects through the control of DNA transcription and protein synthesis.[21] Like its naturally secreted counterpart, levothyroxine is a chiral compound in the L-form.

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption of orally administered levothyroxine from the gastrointestinal tract ranges from 40 to 80%, with the majority of the drug absorbed from the jejunum and upper ileum.[21] Levothyroxine absorption is increased by fasting and decreased in certain malabsorption syndromes, by certain foods, and with age. The bioavailability of the drug is decreased by dietary fiber.[21]

Greater than 99% of circulating thyroid hormones are bound to plasma proteins including thyroxine-binding globulin, transthyretin (previously called 'thyroxine-binding prealbumin'), and albumin.[16] Only free hormone is metabolically active.[16]

The primary pathway of thyroid hormone metabolism is through sequential deiodination.[21] The liver is the main site of T4 deiodination, and along with the kidneys are responsible for about 80% of circulating T3.[28] In addition to deiodination, thyroid hormones are also excreted through the kidneys and metabolized through conjugation and glucuronidation and excreted directly into the bile and the gut where they undergo enterohepatic recirculation.[16]

Half-life elimination is 6–7 days for people with normal lab results; 9–10 days for people with hypothyroidism; 3–4 days for people with hyperthyroidism.[16] Thyroid hormones are primarily eliminated by the kidneys (approximately 80%), with urinary excretion decreasing with age.[16] The remaining 20% of T4 eliminated in the stool.[16]

History

Thyroxine was first isolated in pure form in 1914 at the Mayo Clinic by Edward Calvin Kendall from extracts of hog thyroid glands.[29] The hormone was synthesized in 1927 by British chemists Charles Robert Harington and George Barger.

Society and culture

Economics

As of 2011, levothyroxine was the second most commonly prescribed medication in the United States,[30] with 23.8 million prescriptions filled each year.[31]

In 2016 it became the most commonly prescribed medication in the US, with more than 114 million prescriptions.[8]

Available forms

Levothyroxine for systemic administration is available as an oral tablet, an intramuscular injection, and as a solution for intravenous infusion.[16] Furthermore, levothyroxine is available as both brand-name and generic products.[11] While the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of generic levothyroxine for brand-name levothyroxine in 2004, the decision was met with disagreement by several medical associations.[11] The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), the Endocrine Society, and the American Thyroid Association did not agree with the FDA that brand-name and generic formulations of levothyroxine were bioequivalent.[11] As such, it was recommended that people be started and kept on either brand-name or generic levothyroxine formulations and not changed back and forth from one to the other.[11] For people who do switch products, it is recommended that their TSH and free T4 levels be tested after six weeks to check that they are within normal range.[11]

Common brand names include Eltroxin, Euthyrox, Eutirox, Letrox, Levaxin, Lévothyrox, Levoxyl, L-thyroxine, Thyrax, and Thyrax Duotab in Europe; Thyrox, Thyronorm in South Asia; Unithroid, Eutirox, Synthroid, and Tirosint in North and South America; and Thyrin and Thyrolar in Bangladesh. There are also numerous generic versions.

The related drug dextrothyroxine (D-thyroxine) was used in the past as a treatment for hypercholesterolemia (elevated cholesterol levels) but was withdrawn due to cardiac side effects.

References

- "Levothyroxine Sodium". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Harington CR (1926). "Chemistry of Thyroxine: Constitution and Synthesis of Desiodo-Thyroxine". The Biochemical Journal. 20 (2): 300–13. doi:10.1042/bj0200300. PMC 1251714. PMID 16743659.

- DrugBank DB00451

- King, Tekoa L.; Brucker, Mary C. (2010). Pharmacology for Women's Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 544. ISBN 9781449658007. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Levothyroxine". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 223. ISBN 9781284057560.

- "The Top 300 of 2019". clincalc.com. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Vaidya B, Pearce SH (July 2008). "Management of hypothyroidism in adults". BMJ. 337: a801. doi:10.1136/bmj.a801. PMID 18662921.

- Roberts, Caroline GP; Ladenson, Paul W (2004). "Hypothyroidism". The Lancet. 363 (9411): 793. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15696-1.

- Gaitonde DY, Rowley KD, Sweeney LB (August 2012). "Hypothyroidism: an update". American Family Physician. 86 (3): 244–51. PMID 22962987.

- McAninch EA, Rajan KB, Miller CH, Bianco AC (August 2018). "Systemic Thyroid Hormone Status During Levothyroxine Therapy In Hypothyroidism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01361. PMC 6226605. PMID 30124904.

- Svensson J, Ericsson UB, Nilsson P, Olsson C, Jonsson B, Lindberg B, Ivarsson SA (May 2006). "Levothyroxine treatment reduces thyroid size in children and adolescents with chronic autoimmune thyroiditis". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 91 (5): 1729–34. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2400. PMID 16507633.

- Dietlein M, Wegscheider K, Vaupel R, Schmidt M, Schicha H (2007). "Management of multinodular goiter in Germany (Papillon 2005): do the approaches of thyroid specialists and primary care practitioners differ?". Nuklearmedizin. Nuclear Medicine. 46 (3): 65–75. doi:10.1160/nukmed-0068. PMID 17549317.

- Mandel SJ, Brent GA, Larsen PR (September 1993). "Levothyroxine therapy in patients with thyroid disease". Annals of Internal Medicine. 119 (6): 492–502. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00009. PMID 8357116.

- "Levothyroxine (Lexi-Drugs)". LexiComp. Archived from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- Midgley JE, Larisch R, Dietrich JW, Hoermann R (December 2015). "Variation in the biochemical response to L-thyroxine therapy and relationship with peripheral thyroid hormone conversion efficiency". Endocrine Connections. 4 (4): 196–205. doi:10.1530/EC-15-0056. PMC 4557078. PMID 26335522.

- Hypothyroidism~treatment at eMedicine

- "Synthroid (Levothyroxine Sodium) Drug Information: Uses, Side Effects, Drug Interactions and Warnings". RxList. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- "Effects of Evening vs Morning Levothyroxine Intake: A Randomized Double-blind Crossover Trial". Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- "Novothyrox (levothyroxine sodium tablets, USP)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- Frilling A, Liu C, Weber F (2004). "Benign multinodular goiter". Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 93 (4): 278–81. doi:10.1177/145749690409300405. PMID 15658668.

- Irizarry, Lisandro (23 April 2010). "Toxicity, Thyroid Hormone". WebMd. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- Lilja JJ, Laitinen K, Neuvonen PJ (September 2005). "Effects of grapefruit juice on the absorption of levothyroxine". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 60 (3): 337–41. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02433.x. PMC 1884777. PMID 16120075.

- Benvenga S, Bartolone L, Pappalardo MA, Russo A, Lapa D, Giorgianni G, Saraceno G, Trimarchi F (March 2008). "Altered intestinal absorption of L-thyroxine caused by coffee". Thyroid. Mary Ann Liebert. 18 (3): 293–301. doi:10.1089/thy.2007.0222. PMID 18341376.

- Jasek W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (62nd ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 8133–4. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- Bocchetta A, Loviselli A (September 2006). "Lithium treatment and thyroid abnormalities". Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2 (1): 23. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-2-23. PMC 1584230. PMID 16968542.

- Sherwood, Lauralee (2010). "19 The Peripheral Endocrine Glands". Human Physiology. Brooks/Cole. p. 694. ISBN 978-0-495-39184-5.

- Kendall EC (1915). "The isolation in crystalline form of the compound containing iodin, which occurs in the thyroid: Its chemical nature and physiologic activity". J. Am. Med. Assoc. 64 (25): 2042–2043. doi:10.1001/jama.1915.02570510018005.

- Kleinrock, Michael. "The Use of Medicines in the United States: Review of 2011" (PDF). IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- Moore, Thomas. "Monitoring FDA MedWatch Reports: Signals for Dabigatran and Metoclopramide" (PDF). QuarterWatch. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

External links

- Detailed Euthyrox (Levothroid/Levothyroxine) Consumer Information: Uses, Precautions, Side Effects

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Levothyroxine