Tularemia

Agent

Francisella tularensis

WHERE FOUND

WHERE FOUND

In the U.S., naturally occurring tularemia infections have been reported from all states except Hawaii. Ticks that transmit tularemia to humans include the dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), the wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni), and the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum). Other transmission routes include inhalation and direct inoculation.

INCUBATION PERIOD: 3–5 days (range 1–21

days)

NOTE: The clinical presentation of tularemia will depend on a number of factors, including the portal of entry.

SIGNS AND SYPMTOMS

- Fever, chills

- Headache

- Malaise, fatigue

- Anorexia

- Myalgia

- Chest discomfort, cough

- Sore throat

- Vomiting, diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

(Ulcero) Glandular

- Localized lymphadenopathy

- Cutaneous ulcer at infection site

(not always present)

Oculoglandular

- Photophobia

- Excessive lacrimation

- Conjunctivitis

- Preauricular, submandibular and cervical lymphadenopathy

Oropharyngeal

- Severe throat pain

- Cervical, preparotid, and/or retropharyngeal lymphadenopathy

Pneumonic

- Non-productive cough

- Substernal tightness

- Pleuritic chest pain

- Hilar adenopathy, infiltrate, or pleural effusion may be present on chest X-ray

Typhoidal

- Characterized by any combination of the general symptoms (without localizing symptoms of other syndromes)

GENERAL LABORATORY FINDINGS

- Leukocyte count and sedimentation rate may be normal or elevated

- Thrombocytopenia

- Hyponatremia

- Elevated hepatic transaminases

- Elevated creatine phosphokinase

- Myoglobinuria

- Sterile pyuria

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

- Demonstration of a four-fold change in antibody titer in paired sera; or

- Isolation of organism from a clinical specimen; or

- Detection of organism by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) test or a single elevated serum antibody titer is supportive of the diagnosis; however, a single antibody titer should be confirmed by either one of the methods above.

Treatment

The regimens listed below are guidelines only and may need to be adjusted depending on a patient’s age, medical history, underlying health conditions, pregnancy status or allergies. Consult an infectious disease specialist for the most current treatment guidelines or for individual patient treatment decisions.

| Age Category | Drug | Dosage | Maximum | Duration (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Streptomycin | 1 g IM twice daily | 2 g per day | Minimum 10 |

| Gentamicin* | 5 mg/kg IM or IV daily (with desired peak serum levels of at least 5 mcg/mL) | Monitor serum drug levels | Minimum 10 | |

| Ciprofloxacin* | 400 mg IV or PO twice daily | N/A | 10–14 | |

| Doxycycline | 100 mg IV or PO twice daily | N/A | 14–21 | |

| Children | Streptomycin | 15 mg/kg IM twice daily | 2 g per day | Minimum 10 |

| Gentamicin* | 2.5 mg/kg IM or IV 3 times daily | Monitor serum drug levels and consult a pediatric infectious disease specialist | Minimum 10 | |

| Ciprofloxacin* | 15 mg/kg IV or PO twice daily | 1 g per day | 10 | |

| *Not a U.S. FDA-approved use, but has been used successfully to treat patients with tularemia. | ||||

NOTE: Gentamicin or streptomycin is preferred for treatment of severe tularemia. Doses of both streptomycin and gentamicin should be adjusted for renal insufficiency.

NOTE: Chloramphenicol may be added to streptomycin to treat meningitis.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009. Tularemia—Missouri, 2000-2007. MMWR 58:744–748.

Dennis D, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, et al. Tularemia as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 2001. 285(21): 2763–2773.

Feldman KA, Enscore RE, Lathrop SL, et al. An outbreak of primary pneumonic tularemia on Martha’s Vineyard. NEJM 2001;345: 1601–1606.

Johansson A, Berglund L, Sjöstedt A, Tärnvik. A ciprofloxacin for treatment of tularemia. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:267–8.

Penn RL. Francisella tularensis (Tularemia). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. p. 2674–2685.

Tarnvik A. WHO Guidelines on tularaemia [PDF – 1.2 MB]. Vol. WHO/CDS/EPR/2007.7. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007

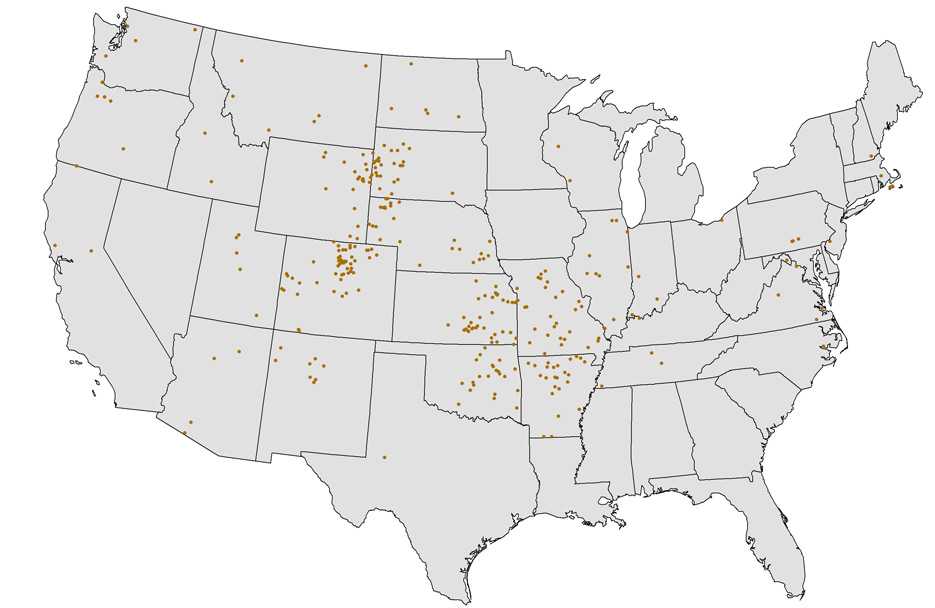

Reported Cases of Tularemia, U.S., 2015

NOTE: Each dot represents one case. Cases are reported from the infected person’s county of residence, not necessarily the place where they were infected.

NOTE: In 2015, no cases of tularemia were reported from Hawaii; 2 cases were reported from Alaska.

- Page last reviewed: October 23, 2014

- Page last updated: February 8, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir