Babesiosis

Agent

Babesia microti and other Babesia species

WHERE FOUND

WHERE FOUND

Babesiosis is most frequently reported from the northeastern and upper midwestern United States in areas where Babesia microti is endemic. Sporadic cases of infection caused by novel Babesia agents have been detected in other U.S. regions, including the West Coast. In addition, transfusion-associated cases of babesiosis can occur anywhere in the country.

INCUBATION PERIOD: 1-9+ weeks

SIGNS AND SYPMTOMS

- Fever, chills, sweats

- Malaise, fatigue

- Myalgia, arthralgia, headache

- Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as anorexia and nausea (less common: abdominal pain, vomiting)

- Dark urine

- Less common: cough, sore throat, emotional lability, depression, photophobia, conjunctival injection

- Mild splenomegaly, mild hepatomegaly, or jaundice may occur in some patients

NOTE: Not all infected persons are symptomatic or febrile. The clinical manifestations, if any, usually develop within several weeks after the exposure but may develop or recur months later (for example, in the context of surgical splenectomy).

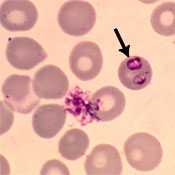

Babesiosis is caused by parasites that infect red blood cells. Most U.S. cases are caused by Babesia microti, which is transmitted by Ixodes scapularis ticks, primarily in the Northeast and upper Midwest. Babesia parasites also can be transmitted via transfusion, anywhere, at any time of the year. To date, no Babesia tests have been licensed for screening blood donors. Congenital transmission also has been reported.

Babesia infection can range from asymptomatic to life threatening. Risk factors for severe babesiosis include asplenia, advanced age, and impaired immune function. Severe cases can be associated with marked thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hemodynamic instability, acute respiratory distress, renal failure, hepatic compromise, altered mental status, and death.

GENERAL LABORATORY FINDINGS

- Decreased hematocrit due to hemolytic anemia

- Thrombocytopenia

- Elevated serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

values - Mildly elevated hepatic transaminase values

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

- Identification of intraerythrocytic Babesia parasites by light microscopic examination of a peripheral blood smear; or

- Positive Babesia (or B. microti) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis; or

- Isolation of Babesia parasites from a whole blood specimen by animal inoculation (in a reference laboratory).

SUPPORTIVE LABORATORY CRITERIA

- Demonstration of a Babesia-specific antibody titer by indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) testing for total immunoglobulin (Ig) or IgG.

NOTE: If the diagnosis of babesiosis is being considered, manual (nonautomated) review of blood smears should be requested explicitly. In symptomatic patients with acute infection, Babesia parasites typically can be detected by blood-smear examination, although multiple smears may need to be examined. Sometimes it can be difficult to distinguish between Babesia and malaria parasites and even between parasites and artifacts (such as stain or platelet debris). Consider having a reference laboratory confirm the diagnosis and the species. In some settings, molecular techniques can be useful for detecting and differentiating among Babesia species.

NOTE: Antibody detection by serologic testing can provide supportive evidence for the diagnosis but does not reliably distinguish between active and prior infection.

Treatment

Treatment decisions and regimens should consider the patient’s age, clinical status, immunocompetence, splenic function, comorbidities, pregnancy status, other medications, and allergies. Expert consultation is recommended for persons who have or are at risk for severe or relapsing infection or who are at either extreme of age.

For ill patients, babesiosis usually is treated for at least 7–10 days with a combination of two medications—typically, either atovaquone PLUS azithromycin; OR clindamycin PLUS quinine (this combination is the standard of care for severely ill patients). The typical regimens for adults are provided in the table below.

| Age Category | Drug | Dosage | Maximum | Duration (Days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Prescribe together | Atovaquone | 750 mg orally every 12 hours | N/A | 7-10 |

| Azithromycin | On the first day, give a total dose in the range of 500–1000 mg orally; on subsequent days, give a total daily dose in the range of 250–1000 mg* | 1000 mg per day | 7-10 | ||

| OR | |||||

| Prescribe together | Clindamycin** | 300–600 mg IV every 6 hours OR 600 mg orally every 8 hours** |

N/A | 7-10 | |

| Quinine** | 650 mg orally every 6–8 hours | N/A | 7-10 | ||

|

* The upper end of the range (600–1000 mg per day) has been used for adults who are immunocompromised. ** The standard of care for patients with severe babesiosis (e.g., with parasitemia levels ≥10% and/or organ-system dysfunction) is quinine plus NOTE: Most persons without clinical manifestations of infection do not require treatment. However, consider treating persons who have had demonstrable parasitemia for more than 3 months. |

|||||

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Babesiosis surveillance—18 states, 2011. MMWR 2012;61:505–9.

Herwaldt BL, Linden JV, Bosserman E, Young C, Olkowska D, Wilson M. Transfusion-associated babesiosis in the United States: a description of cases. Ann Intern Med 2011;115:509–19.

Vannier E, Krause PJ. Human babesiosis. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2397–407.

Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:1089–134. Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:941.

Wormser GP, Prasad A, Neuhaus E, et al. Emergence of resistance to azithromycin-atovaquone in immunocompromised patients with Babesia microti infection. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:381–6.

Reported Cases of Babesiosis, U.S., 2015

NOTE: Each dot represents one case. Cases are reported from the infected person’s county of residence, not necessarily the place where they were infected.

NOTE: During 2015, babesiosis was reportable in Alabama, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

- Page last reviewed: October 23, 2014

- Page last updated: February 8, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir