Medical Screening of US-Bound Refugees

Congolese Refugee Health Profile

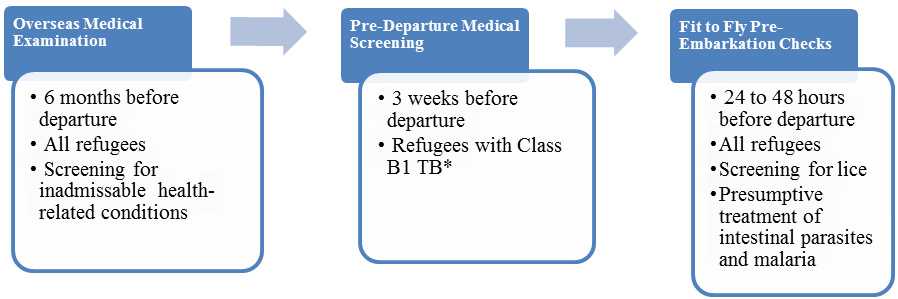

Congolese refugees who have been identified for resettlement in the United States receive medical assessments (Figure 7). Some assessments occur several months prior to the refugees’ departure and some occur immediately before departure to the United States.

Figure 7: Medical assessment of United States-bound Congolese refugees

Overseas Medical Examination

An overseas medical examination is mandatory for all refugees resettling in the United States and must be performed according to CDC’s Technical Instructions. The purpose of the medical examination is to identify applicants with inadmissible health-related conditions, and they are performed by panel physicians who are selected by US Department of State consular officials. CDC provides the regulatory and technical oversight and training for all panel physicians. Information collected during the refugee overseas medical examination is reported to EDN and is available to state refugee health programs in the states where the refugees are resettled.

Refugees do not have to receive any vaccines before they are admitted into the United States. Vaccines given to Congolese refugees during the overseas medical examination vary depending on the country where they reside during the examination.

Pre-Departure Medical Screening

Congolese refugees receive a pre-departure medical screening about 3 weeks before leaving for the United States if they have been previously diagnosed with class B1 TB (TB fully treated using directly observed therapy, or abnormal chest x-ray with negative sputum smears and cultures, or extrapulmonary TB). The screening includes a repeat physical examination with a focus on TB signs and symptoms, chest x-ray, and sputum collection for acid-fast bacilli smear microscopy.

Pre-Embarkation Checks

IOM clinicians perform 2 pre-embarkation checks within 48 hours of the refugee’s departure for the United States to assess his or her fitness for travel. During this assessment, the clinician administers presumptive therapy for intestinal parasites (worms) and malaria. Presumptive therapy is treatment of individuals who have a high likelihood of asymptomatic or sub-clinical infection without, or prior to, results from confirmatory laboratory tests.

Congolese refugees departing from Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Rwanda receive pre-departure treatment for soil-transmitted helminths, schistosomiasis, and malaria according to current CDC guidance. Except when contraindicated, refugees are treated for soil-transmitted helminths with a single dose of albendazole, schistosomiasis with standard dose of praziquantel (divided into two doses for better tolerance), and malaria with a 6-dose schedule of artemether-lumefantrine. Management of Strongyloides in Congolese refugees is deferred until the refugee’s arrival in the United States. Guidance for this is available in the Domestic Intestinal Parasite Screening Guidelines. Refugees from sub-Saharan Africa are normally given presumptive treatment for infection with Strongyloides with ivermectin; however, since DRC is a Loa loa-endemic country, Congolese refugees should not receive presumptive ivermectin for strongyloidiasis prior to departure because of the risk of encephalopathy.

Information on presumptive therapy for intestinal parasites will be noted on IOM’s Pre-Departure Medical Screening Form, which is included in the packet provided to each refugee before he or she departs. Information on presumptive therapy for intestinal parasites given to refugees will also appear in EDN.

Surveillance

Active surveillance for communicable diseases of public health significance (such as TB) takes place through all phases of overseas medical processing. This surveillance is designed to identify refugees with conditions that may result in deferred travel or other interventions. In addition, when disease outbreaks occur in the camps, IOM coordinates with the local implementing partners to identify refugees in the resettlement program who may be affected. Depending on the nature of the disease outbreak, various interventions may then be used, such as deferral of travel, additional vaccinations, and presumptive or directed therapy.

Post-Arrival Medical Screening

Once refugees have arrived in the United States, CDC recommends that they receive a post-arrival medical screening (domestic medical screening) within 30 days. The Office of Refugee Resettlement reimburses providers for screenings conducted during the first 90 days after arrival. The purpose of these more comprehensive examinations is to identify conditions for which refugees may not have been screened during their overseas medical examinations. The examinations also introduce refugees to the US healthcare system. CDC provides guidelines and recommendations while state health departments oversee and administer the domestic medical screenings. State refugee health programs determine who conducts the examinations within their jurisdiction; these may be performed by health department personnel or private physicians. Data from the screenings are collected by most state health departments.

Health Conditions for Healthcare Providers to Consider in Post-Arrival Medical Screening of Congolese Refugees

In addition to the standard guidelines for post-arrival medical screening of newly arriving refugees, clinicians should consider the following health conditions.

Malaria

According to the current United States domestic screening guidelines for malaria, refugees who have received presumptive treatment prior to departure need no further evaluation for malaria unless they demonstrate signs or symptoms of infection. CDC recommends that Congolese refugees originating from other sub-Saharan African countries who have not received pre-departure therapy either receive presumptive treatment when they arrive or have laboratory screening with a blood smear.

Strongyloidiasis

CDC currently recommends that all United States-bound Congolese refugees either be presumptively treated OR tested and treated (if positive) for strongyloidiasis after arrival in the United States. Currently, only Congolese refugees departing from Kenya receive pre-departure treatment for strongyloidiasis.

The treatment of choice for Strongyloides infection is ivermectin, a single dose for 2 consecutive days. However, the management of Strongyloides infection in the Congolese refugees is complicated by the possibility of co-infection with the parasite Loa loa, also known as “eye worm.” Persons with a high blood level (microfilarial load) of Loa loa who are given ivermectin therapy can develop severe encephalopathy. Although this is rare, CDC recommends that a patient originating from, or transiting through, a Loa loa endemic country be tested prior to ivermectin use to ensure that he or she does not have a high microfilarial load. Please refer to the list of Loa loa-endemic countries.

Use one of these three approaches to address Strongyloides infection in Congolese who are at risk of co-infection with Loa loa infection:

- Presumptive treatment with ivermectin after testing for Loa loa - To diagnose Loa loa, a daytime blood smear (thick and thin, same test as for malaria) can be done between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. If there are no Loa loa parasites observed, ivermectin may be safely used to presumptively treat the refugee.

- Presumptive treatment with “high-dose” albendazole without testing for Loa loa - Presumptively treat refugees with “high-dose” albendazole without testing for Loa loa infection. The dosing recommended for treatment of Strongyloides infection is albendazole 400 mg twice a day for 7 days.

- Test for Strongyloides, Loa loa and treatment if positive - Test the refugee for Strongyloides infection and only treat (for Strongyloides) those whose results are positive. Serology is the most sensitive test for detecting Strongyloides infection. Stool ova and parasite examination or stool agar culture may be used as additional tests but should not be used alone because of poor sensitivity. Those with positive test result (for Strongyloides) could either be treated with ivermectin (if a daytime blood smear is negative as described above) or with the 7-day course of albendazole.

For more information, please see the Domestic Intestinal Parasite Guidelines for refugees.

Schistosomiasis

Refugees originating in sub-Saharan Africa without a contraindication receive a treatment dose of praziquantel prior to departure, which presumptively treats a majority of infected individuals. Currently, those Congolese refugees from the asylum countries of Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda, and South Africa should be receiving praziquantel prior to departure. However, a treatment dose of praziquantel is not 100% effective and any refugee with signs or symptoms of active disease, most often, a persistently elevated eosinophil count, may need further evaluation for schistosomiasis. Please see Presumptive Treatment and Screening for Strongyloidiasis, Schistosomiasis, and Infections Caused by Soil-Transmitted Helminths for Refugees for additional information on domestic medical screening.

Filariasis

The filarial diseases are caused by nematodes transmitted to humans, most commonly through black flies and mosquitoes. The 3 most common infections, all endemic to DRC, are loiasis, lymphatic filariasis, and onchocerciasis. The filarial infections are common in the DRC and co-infection is common. They may persist for a decade or more and some of the complications may be permanent. Most people infected with these nematodes will never develop symptoms. The most common clinical sign in refugees is a persistent elevated eosinophil count. Therefore, these parasites need to be considered in Congolese refugees with a persistent elevated eosinophil count and in those with symptoms more specific to each nematode.

Loiasis, (also known as “eye worm”), caused by the parasitic roundworm Loa loa, is transmitted by red (chrysops) flies and is endemic through most of DRC although it is particularly common in certain focal areas. Most infected individuals have no symptoms, but common clinical manifestations include an increased eosinophil count, recurrent episodes of transient itchy swellings (local angioedema) usually found on the limbs or near joints and sometimes referred to as “Calabar swellings”, and “eye worm”. Eye worm is the visible migration of the adult worm across the surface of the eye which may be associated with eye congestion, itching, pain, and light sensitivity. Other symptoms include generalized itching, hives, muscle pains, joint aches, fatigue, and the visible migrating worm under the surface of the skin. Infection does occur in the absence of an elevated eosinophil count.

Lymphatic filariasis, most commonly caused by the nematode Wuchereria bancrofti, is transmitted to humans by mosquito vectors. Lymphatic filariasis is distributed throughout DRC as well as all major East African countries of asylum. Most infected persons will never develop symptoms. The most common clinical manifestations are a persistently elevated eosinophil count, and a lymphedema that usually affects the legs but also occurs in the arms, breasts, and genitalia (especially hydrocele or swelling of the scrotum in males). Infection does occur in the absence of an elevated eosinophil count. When the swelling is accompanied by hardening and thickening of the skin it is commonly referred to as elephantiasis. This condition predisposes patients to bacterial infections.

Onchocerciasis, caused by Onchocerca volvulus, is transmitted to humans through the bite of a blackfly. Onchocerciasis is found throughout most of DRC as well as in areas of Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. Common clinical manifestations include generalized itching, nodules under the skin, rashes and, most concerning, visual changes (commonly known as “river blindness”). When larva die within the eye they initially cause reversible lesions of the cornea. However, with time they may result in permanent clouding of the cornea and blindness. In addition, inflammation of the optic nerve may occur, resulting in vision loss. Although an elevated eosinophil count is common, infection does occur in the absence of an elevated count.

Diagnosis and treatment of filariasis is complicated and beyond the scope of this document. Further information on each parasite may be obtained at the CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases. CDC also offers diagnostic and treatment assistance.

African Trypanosomiasis

African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness, is an insect borne infection transmitted by tsetse flies. It is caused by microscopic parasites of the species Trypanosoma brucei. There are two subspecies of T. brucei, T.b. Rhodensiense (East African) and T.b. gambiense (West African). Refugees from the DRC may be at risk of West African trypanosomiasis (Trypanosoma brucei gambiense) where West African sleeping sickness is endemic, although most of the refugees report being from non-endemic areas of DRC. Depending on migration route, refugees may also be at risk for T.b. Rhodensiense which is most endemic in Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi and Zambia. T.b. Rhodensiense is less common and has a more acute onset and would be observed at the time of migration or shortly following arrival and would be characterized by fevers, headache, muscle and joint aches, enlarged lymph nodes and is frequently accompanied by a large sore (a chancre) at the bite site. There is relatively rapid clinical decline without treatment with mental disorientation, other neurologic symptoms, coma resulting in death within months.

T.b. gambiense, more common and of greater concern in refugees, since it is more common and may be more insidious occurring months to years after after infection. Symptoms of West African trypanosomiasis typically emerge and include fever, rash, swelling of the hands and face, headaches, fatigue, myalgias and arthralgias, pruritis, and lymphadenopathy. As disease progresses, weight loss ensues with progressive confusion, personality changes, daytime sleepiness with nighttime sleep disturbances, and other neurologic signs and symptoms such as paralysis, ataxia, and balance problems. If left untreated, neurologic symptoms will progress until eventually death occurs, usually years after initial infection.

The diagnosis should be considered in any refugee with potential exposure and unexplained signs or symptoms such as weight loss and neurologic decline.

More information on the biology, diagnosis, and treatment of these diseases may be found on the CDC Parasitic diseases website. CDC also offers diagnostic and treatment assistance.

Syphilis

Given the low prevalence of syphilis in the Congolese refugee population (Table 5), screening for syphilis should follow the current CDC domestic refugee medical screening guidelines. That is, providers should rely on the results of the pre-departure testing, if it is available.

Repeat screening should be done domestically with a nontreponemal test (e.g., Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] or rapid plasma reagin [RPR]) in the following situations:

- For all refugees ≥15 years old if overseas results are not available.

- For children <15 years old who are at risk (i.e., mother who tests positive for syphilis) should be evaluated according to the Congenital Syphilis section of the CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010.

- Any refugee who has a history of sexual assault

Refugees with positive nontreponemal screening test results should have confirmatory treponemal testing.

HIV Infection

HIV testing is offered to refugees by many state health departments. The current domestic refugee screening guidelines for HIV recommend universal screening of refugees after arrival. This is especially important since in January 2010, the requirement for HIV testing of adult refugees prior to US resettlement was removed. The known history of sexual violence in the Congolese refugee population and data that indicate relatively higher rates than most refugee populations reinforce the importance of HIV screening in Congolese refugees.

Chlamydia and Gonorrhea

The current Refugee Domestic Screening Guidelines for Sexually Transmitted Diseases suggest routine screening for chlamydia in women ≤25 years old who are sexually active, or testing refugees for chlamydia and gonorrhea if there are known risk factors or signs of infection.

There are limited data available on rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea in Congolese refugees (Table 5). Given the lack of data and well-documented high rates of sexual violence, it is reasonable to extend screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea to both female and male adult refugees as well as any child with a history of sexual abuse or signs of infection (e.g., leukesterase).

Chronic Viral Hepatitis

The most common chronic viral hepatitis encountered in refugees is hepatitis B. Clinicians should screen all Congolese refugees for chronic infection with hepatitis B virus on arrival to the U.S., as recommended in the CDC Guidelines for the U.S. Domestic Medical Examination for Newly Arriving Refugees. Some Congolese refugees may have received one or more doses of hepatitis B vaccine. Hepatitis B surface antibody may be positive if measured after the first or second dose of vaccination and does not necessarily indicate long-term immunity. Congolese refugees generally do not receive the full hepatitis B series prior to migration, with the exception of refugees departing from Kenya (since September 2013). Even if vaccinated, refugees should be screened for hepatitis B infection if previous results are not available since vaccination does not protect a person with precedent infection. If the refugee is not infected with hepatitis B virus, and has not received an acceptable full course of hepatitis B immunization, the vaccine course should be completed according to ACIP guidelines. More information and guidance about hepatitis B infection and prevention in refugees is available in the domestic screening guidelines. There are no published or other available screening data on the prevalence of hepatitis C in Congolese refugees and screening guidelines remain consistent with the broader screening guidelines for arriving refugees.

Anemias

Anemia is frequently caused by multiple factors such as nutritional deficiency (e.g., low iron intake), parasitic infections such as hookworm and malaria, thalassemias, and hemoglobinopathies, although it may indicate other underlying diseases (e.g., cancer, ulcers). There will be an expected higher rate of sickle cell anemia (SCA) in Congolese refugees based on available country prevalence data, and physicians may consider screening for SCA, especially in refugees found to have anemia. Screening may lead to appropriate management and monitoring of those with SCA as well as to counseling of those who have sickle cell trait.

In addition, glucose-6-dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) deficiency, an enzyme deficiency, is common in certain populations and has been estimated to occur in 19% of the population of the DRC 17. Unlike most inherited hematologic disorders which result in anemia (e.g., decreased hemoglobin or change in indices such as MCV or RDW), G-6-PD deficiency is not evident on routine blood testing or blood smears. Under certain circumstances, G-6-PD deficiency may result in acute hemolytic anemia, usually after a refugee with this condition is exposed to certain medications, foods, or even infections. Therefore, certain medications with strong oxidizing potential [PDF - 1 page] (e.g., primaquine for malaria, dapsone) should be avoided if the patient’s G-6-PD status is unknown (or the patient should be tested for G-6-PD deficiency before he or she takes the medication). Other common oxidizing medications should also be used with caution or avoided in this population, including sulfa-based medications; unless the patient’s G-6-PD status is known.

Alpha thalassemia should also be considered in patients with an anemia.

Hypertension, Dyslipidemia, and Diabetes

Routine blood pressure screening and monitoring is suggested in newly arriving Congolese refugees, as with all populations. Diabetes should be considered when there are risk factors (e.g., obesity) or other common signs are present (e.g., hyperglycemia on blood chemistry, glucosuria). Lipid screening should be considered according to United States’ guidelines.

References

- MAP: Malaria Atlas Project. Wellcome Trust. Population estimates for G-6-PD deficiency table for the Congo. Available at: http://www.map.ox.ac.uk/browse-resources/g6pd/g6pdd-estimates-table/cog/. Last accessed August 5, 2013

- Page last reviewed: August 29, 2014

- Page last updated: August 29, 2014

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir