Healthcare Access and Conditions in Refugee Camps

Congolese Refugee Health Profile

Refugee camps in Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda (the 4 top countries sending Congolese refugees to the United States) each have different nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that provide inpatient and outpatient medical care and community health education to camp residents. UNHCR collects health information in refugee camps and reports this information in their Health Information System (HIS). Some services offered by the NGOs include pediatrics and integrated management of childhood illness, reproductive health, psychiatric consultation, emergency medical services and referrals, basic laboratory services, tuberculosis (TB) management (directly observed therapy with first-line agents), voluntary testing and counseling for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) with referral services for antiretroviral treatment, and nutrition promotion.

Immunizations

Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda administer vaccines in line with the World Health Organizations (WHO) Expanded Program on Immunization. Precise estimates of vaccine coverage in camps are difficult to obtain because the exact number of people living in the camps is not known. Supplemental mass immunization campaigns are also carried out by NGOs following announcements from the host country governments. If appropriate documentation from the refugee is available, the vaccinations given to that person will be noted on the US Department of State’s form DS-3025, which is included in the health information packet provided to each refugee before he or she departs. DS forms are the forms used by physicians to complete the overseas medical screening examinations. The health information packet is supplied by IOM and contains the refugees’ medical screening examination information for reference upon the refugees’ arrival in the United States. Additionally, IOM’s Pre-Departure Medical Screening Form will note vaccination information for individual refugees. All vaccination information will also appear in CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification system (EDN).

Reproductive Health

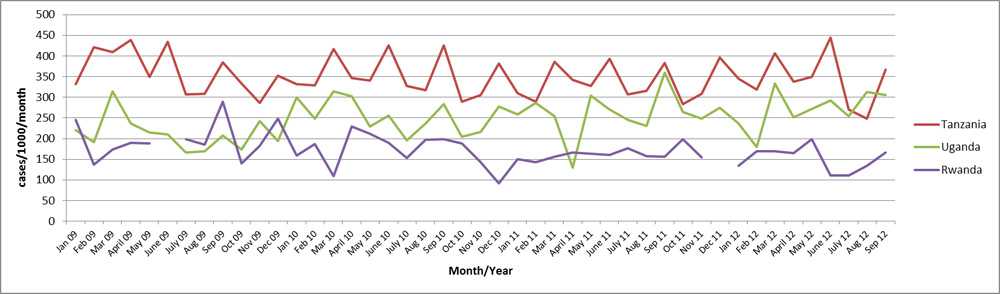

Birthrates in refugee camps in Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda vary considerably (Figure 6). There are no data available for Burundi. The percent of births that are attended by a skilled midwife or a health worker with midwifery skills varies depending on the camp and country. In 2012 the percentages of births attended by a skilled attendant in the refugee camps were: 100% for Burundi, 92% for Rwanda, 100% for Tanzania, and 93% for Uganda 6. It should be noted that the above statistics apply to refugees from multiple countries that are living in the camps in Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda, not refugees exclusively from DRC. Additionally, Congolese refugees may not feel comfortable discussing sexuality and gynecological issues with non-family members, especially male clinicians.

Figure 6: Crude birth rates in refugee camps in Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda by month, 2009–2012

Sexual- and Gender-Based Violence

The conflict in eastern DRC has been marked by numerous human rights abuses, including sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). Reports include gang rapes, sexual slavery, purposeful mutilation of women’s genitalia, and killing of rape victims 7. One study estimated that 48 women are raped every hour in DRC, which is a little over 1,150 women a day 8. According to a population-based study conducted in the eastern DRC in 2010, rates of reported sexual violence were 40% among women, and 24% among men. In addition to sexual violence, 20% of the adult population in the study reported serving as combatants at some point in their lifetime, the majority of whom reported being conscripted into armed groups 9. The brutality of such sexual violence has resulted in unprecedented rates of trauma, physical injury including fistula, pregnancy, infertility, genital mutilation, and HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases. 50% of rape victims in the DRC are believed not to have access to medical treatment 10.

The threat of SGBV is also present in the refugee camp environment, particularly where women and girls must travel on foot outside the camps to collect firewood, risking harassment, rape, and other abuses. Service providers in Rwanda noted that limited work opportunities force some women and girls into abusive relationships or “survival sex,” i.e., coerced sex in exchange for temporary access to food, shelter, or protection. Additionally, a refugee’s access to mental health services in these camps is often extremely limited; in 1 camp, 1 psychological nurse may be responsible for 16,000 refugees 11).

The psychosocial consequences of being raped are devastating. Fear, shame, insomnia, and nightmares are frequently noted among sexual violence survivors. In eastern DRC, rape is highly stigmatized and social problems include spousal abandonment, inability to marry, and ostracism by the community. Spousal and community abandonment can lead to isolation and homelessness 12.

However, despite experiences of SGBV being common within the Congolese refugee population, SGBV is an extremely sensitive issue, and associated with much shame. Service providers with experience treating these patients recommend that public health officials not ask intrusive personal questions upon the patient’s initial screening and early visits, but wait until the patient trusts the service providers.

While much attention has been paid to sexual violence allegedly committed by paramilitary personnel and soldiers, intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV) has been less visible. A Demographic and Health Survey conducted in 2007 suggests that this is a particularly large problem in the DRC, with approximately 35% of women reporting IPSV 13. From a nationally representative household survey conducted in all 11 provinces of DRC in 2010, the total number of women estimated to have suffered IPSV ranged from 3.07 million to 3.37 million, with the number of women reporting IPSV roughly 1.8 times the number of women reporting rape 14. This result is in line with international research indicating that intimate partner sexual violence is the most pervasive form of violence against women 15.

Female Genital Cutting

The practice of female genital cutting (FGC, also referred to as female genital mutilation), which is the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for cultural, religious, or non-therapeutic reasons, is known to exist in the DRC, but current data on the prevalence of FGC are not available (WHO). However, in a 2007 report, UNICEF stated that the prevalence of FGC in the DRC was estimated to be less than 5% 16.

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Public Health and HIV Annual Report (2012).

- Wakabi, Wairagala. Sexual violence increasing in Democratic Republic of Congo. The Lancet 2008; 371:15-16.

- Peterman A, Palermo T, Bredenkamp C. Estimates and determinants of sexual violence against women in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1060-7.

- Johnson K et al. Association of Sexual Violence and Human Rights Violations with Physical and Mental Health in Territories of the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Journal of the American Medical Association 2010; Vol. 304. No. 5: 553-62. Available at: http://www.lawryresearch.com/553.full.pdf [PDF - 10 pages]

- Michalopoulos L. Exploration of Cross-cultural Adaptability of PTSD among Trauma Survivors in Northern Iraq, Thailand, and the Democratic Republic of Congo: Application of Item Response Theory and Classical Test Theory. Thesis University of Maryland Archive Jan. 2013. Available at: http://archive.hshsl.umaryland.edu/handle/10713/2766 [cited Dec 2013].

- Fuys, Andrew, and Sandra Vines. (2013) “Increasing Congolese Refugee Arrivals: Insights for Preparation.” Executive Summary. Washington DC: Refugee Council USA. Print. February 15. Report from Associate Directors for International Programs and Resettlement and Integration, Church World Service.

- Now, the World Is Without Me: An Investigation of Sexual Violence in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Harvard Humanitarian Initiative. April 2010. Available at: http://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/DRC-sexual-violence-2010-04.pdf [PDF - 72 pages] [cited Oct 2013].

- Democratic Republic of Congo Demographic and Health Survey 2007 (DRC-DHS); Available at: http://www.measuredhs.com/publications/publication-fr208-dhs-final-reports.cfm

- Peterman A, Palermo T, Bredenkamp C, et al. Estimates and Determinants of Sexual Violence against Women in the Democratic Republic of Congo. American Journal of Public Health 2011; Vol. 101, No. 6:1060-1067.

- World Health Organization 2013. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85239/1/9789241564625_eng.pdf [PDF - 57 pages]

- United Nations Children's Fund. Coordinated Strategy to Abandon Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in One Generation: A Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming 2007. Available at: http://www.childinfo.org/files/fgmc_Coordinated_Strategy_to_Abandon_FGMC__in_One_Generation_eng.pdf [PDF - 56 pages]

- Page last reviewed: August 29, 2014

- Page last updated: August 29, 2014

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir