Global Health Security: International Health Regulations (IHR)

Protecting People Every Day

With the signing of the revised International Health Regulations (IHR) in 2005, the international community agreed to improve the detection and reporting of potential public health emergencies worldwide. The revised IHR better address today's global health security concerns and are a critical part of protecting global health. The regulations require that all countries have the ability to detect, assess, report and respond to public health events.

CDC is currently working with countries around the globe to help meet the goals of the IHR. CDC’s global programs address over 400 diseases, health threats, and conditions that are major causes of death, disease, and disability. Our global programs are run by world leaders in epidemiology, surveillance, informatics, laboratory systems, and other essential disciplines. Through partnerships with other countries' ministries of health, CDC is improving the quantity and quality of critical public health services.

Spotlight

IHR basics

The IHR are a framework that will help countries minimize the impact and spread of public health threats. As an international treaty, the IHR are legally binding; all countries must report events of international public health importance. Countries are using the IHR framework to prevent and control global health threats while keeping international travel and trade as open as possible. The IHR, which are coordinated by the World Health Organization (WHO), aims to keep the world informed about public health risks and events.

Did You Know?

U.S. government agencies have just 48 hours to assess the situation after learning about a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

Find answers to more questions about how the IHR have changed the way we handle outbreaks and other public health threats.

The IHR require that all countries have the ability to do the following:

- Detect: Make sure surveillance systems and laboratories can detect potential threats

- Assess: Work together with other countries to make decisions in public health emergencies

- Report: Report specific diseases, plus any potential international public health emergencies, through participation in a network of National Focal Points

- Respond: Respond to public health events

The IHR also include specific measures countries can take at ports, airports and ground crossings to limit the spread of health risks to neighboring countries, and to prevent unwarranted travel and trade restrictions.1

IHR: Made for today’s health threats

In today's interconnected society, it's more important than ever to make sure all countries are able to respond to and contain public health threats.

In 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) threatened global health, showing us how easily an outbreak can spread. Recently, the Ebola epidemic in West Africa and outbreaks of MERS-CoV have shown that we are only as safe as the most fragile state. All countries have a responsibility to one another to build healthcare systems that are strong and that work to identify and contain public health events before they spread.

While previous regulations required countries to report incidents of cholera, plague, and yellow fever, the revised IHR are more flexible and future-oriented, requiring countries to consider the possible impact of all hazards, whether they occur naturally, accidentally, or intentionally.2 The IHR cover all events that might potentially become a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

And global health security is not just a health issue; a crisis such as HIV or Ebola can devastate economies and keep countries from developing. The World Bank Group estimates that Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone together will lose at least $1.6 billion in forgone economic growth in 2015 as a result of the Ebola epidemic.3 The impact of this kind of economic devastation reaches farther and wider than ever.4

The IHR also serve as a foundation for the CDC and the Global Health Security Agenda. The GHS Agenda is "an effort by nations, international organizations, and civil society to accelerate progress toward a world safe and secure from infectious disease threats; to promote global health security as an international priority; and to spur progress toward full implementation of the IHR."5

The GHS Agenda provides 11 clear targets which will serve as a road map to help countries create systems that are able to prevent, detect and respond to health threats. The GHS Agenda recognizes the challenges countries are facing, laying out practical and concrete steps countries can take toward strengthening their health systems, as well as ways in which countries can support each other.

Protecting people

IHR Infographic

One of the most important aspects of IHR is the requirement that countries will detect and report events that may constitute a potential public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

Under IHR, a PHEIC is declared by the World Health Organization if the situation meets 2 of 4 criteria:

- Is the public health impact of the event serious?

- Is the event unusual or unexpected?

- Is there a significant risk of international spread?

- Is there a significant risk of international travel or trade restrictions?6

Once a WHO member country identifies an event of concern, the country must assess the public health risks of the event within 48 hours. If the event is determined to be notifiable under the IHR, the country must report the information to WHO within 24 hours.

Some diseases always require reporting under the IHR, no matter when or where they occur, while others become notifiable when they represent an unusual risk or situation.

Always Notifiable7:

- Smallpox

- Poliomyelitis due to wild-type poliovirus

- Human influenza caused by a new subtype

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

Other Potentially Notifiable Events:

- May include cholera, pneumonic plague, yellow fever, viral hemorrhagic fever, and West Nile fever, as well as any others that meet the criteria laid out by the IHR.

- Other biological, radiological, or chemical events that meet IHR criteria8

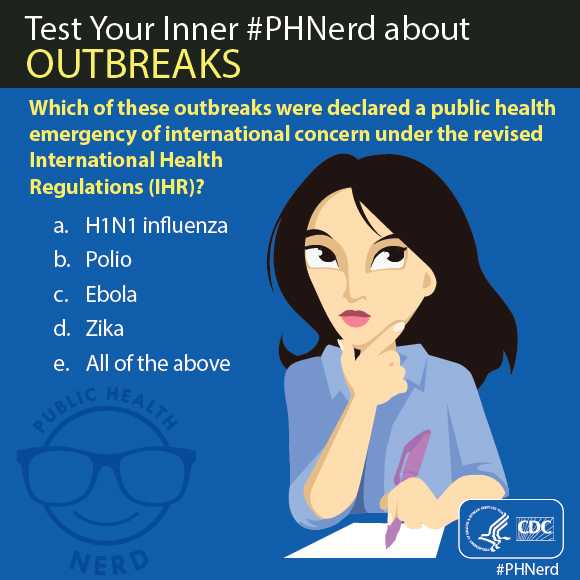

Since the revised IHR were put into place, four PHEICs have been declared by WHO:

- H1N1 influenza (2009)

- Polio (2014)

- Ebola (2014)

- Zika virus (2016)

2014 and 2015 have been unprecedented years for potential PHEICs.9 In the months from January 2014 to February 2015, 321 possible PHEICs were reported to WHO.10 WHO posted more than 400 updates and announcements on their event information site for National IHR Focal Points, relating to 79 public health events and regional updates. Most postings concerned the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) event, the influenza A (H7N9) virus event in China, and the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa.

When a PHEIC is declared, WHO helps coordinate an immediate response with the affected country and with other countries around the world.

IHR timeline

The idea that a health threat in one part of the world can impact other parts of the world is not new. Over time, there have been a series of agreements between countries to address the potential spread of disease, beginning with the International Sanitary Convention in 1892 and continuing until today with the International Health Regulations11.

The IHR were originally written in 1969, and were revised in 2005, following the 2003 epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). After the SARS epidemic, it became clear that stronger systems were needed to detect, assess, report, and respond to public health events.

The revised IHR entered into force for the United States on July 18, 2007.

Currently, countries have been given an extension until 2016 to finish meeting IHR goals. The original timeline for IHR implementation is as follows:

- May 2005: World Health Assembly approved revised IHR

- December 2006: United States accepted the revised IHR

- June 15, 2007: Initial start date for revised IHR

- June 2009: Within 2 years after IHR enters into force, Member Countries complete assessment of the ability of their national structures and resources to meet minimum core capacities*

- 2012: Within 5 years after IHR enters into force, Member Countries achieve the required minimum level of core capacities, unless WHO grants an extension

- 2014: End of 2-year extensions on achieving core capacity, unless an exceptional circumstance exists and a further extension is granted by WHO

- 2016: End of final 2-year extensions (for exceptional circumstances) on achieving core capacities

*Core capacities as listed in Annex 1 of the IHR12

When countries committed to the IHR in 2005, the first target date for achieving its goals was set for 2012. By that date, however, fewer than 20% of countries had met IHR goals. After a 2 year extension, in 2014, 64 countries reported fully achieving the IHR core capacities. Only about 1/3 of the countries in the world currently have the ability to assess, detect and respond to public health emergencies.13

Global participation in the IHR

The IHR represent an agreement between 196 countries, including all WHO Member States, to work together for global health security.14

In the U.S., CDC works with state and local reporting and response networks to receive information at the federal level and then respond to events of concern at the local and federal levels. The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has assumed the lead role in carrying out the reporting requirements for IHR (2005). The Health and Human Services' Secretary's Operations Center (SOC) is the National Focal Point responsible for reporting events to WHO.

Other federal agencies supporting IHR implementation include the Department of Agriculture, Department of Commerce, Department of Defense, Department of Energy, Department of Homeland Security, Department of Justice, Department of State, Department of the Treasury, Department of Transportation, Department of Veterans Affairs, Environmental Protection Agency, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Office of Management and Budget, Office of Science and Technology Policy, U.S. Agency for International Development, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, U.S. Trade Representative, and the United States Postal Service.15

For More Information

References

- WHO. Strengthening health security by implementing the International Health Regulations (2005). Page accessed 6/19/15

- Gostin, Lawrence, The International Health Regulations and beyond; The Lancet, Vol. 4, Issue 10, 606–607

- World Bank. World Bank Group Ebola Response Fact Sheet. Page accessed 6/24/15

- Heymann, David L et al., Global health security: the wider lessons from the west African Ebola virus disease epidemic;

The Lancet, Vol. 385, Issue 9980, 1884 - 1901 - CDC. Global Health Security Agenda. Page accessed 6/19/15

- WHO. IHR Procedures concerning public health emergencies of international concern (PHEIC). Page accessed 6/26/15

- WHO. Case definitions for the four diseases requiring notification in all circumstances under the International Health Regulations (2005). Page accessed 6/26/15

- CDC. Global Health – International Health Regulations. Page accessed 6/26/15

- WHO.Implementation of the International Health Regulations (2005) [662 KB, 14 Pages].

- Katz R, Fischer J. The Revised International Health Regulations: A Framework for Global Pandemic Response. Global Health Governance, Volume 3, Number 2, Spring 2010

- WHO. International Health Regulations (2005). Page accessed 6/26/15

- Katz R, Dowell S. Time for an International Health Regulations Review Conference. Lancet Global Health 2015. , Published Online May 8, 2015. July 2015. Vol 3(7), e352-353

- WHO. Strengthening health security by implementing the International Health Regulations (2005). Page accessed 6/19/15

- CDC. Global Health – International Heath Regulations – Spotlight. Page accessed 6/26/15

- Page last reviewed: February 8, 2016

- Page last updated: February 8, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir