Protecting Mothers and Babies

Humanitarian emergencies often disproportionately affect women of reproductive age and children. During a response, applying public health approaches that are both locally adapted and sustainable can improve outcomes and strengthen the resilience of women, children, adolescents, and their communities for generations.

Small Changes, Big Results

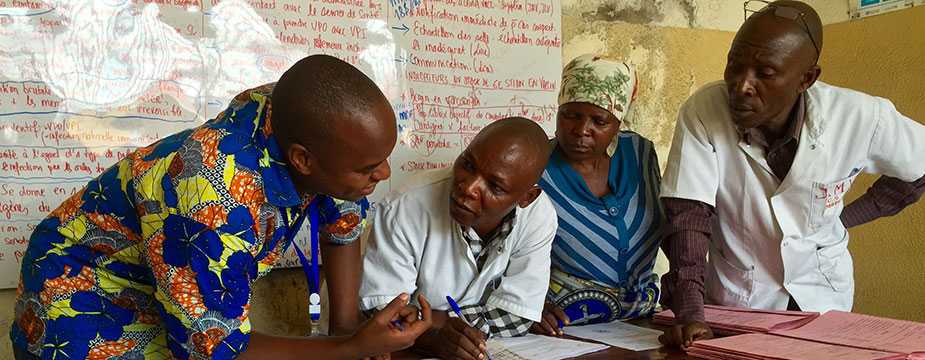

While reviewing maternal and newborn health records with a midwife (center) in Goma, DRC, she had to leave twice to deliver babies (Source: Alaine Knipes, CDC)

Kate Meehan

Though many of the rural healthcare facilities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are small, they are often all that stands between women and potentially fatal situations. For decades the DRC has been plagued by violence, which has recently increased in North Kivu Province.

Our research project aims to improve maternal and newborn health (MNH) in conflict settings. We are working with 12 healthcare facilities, which can be as much as a two-day walk through the forest from the closest road. Project partners train facility staff to work in teams to identify areas that can be improved, test potential solutions, and incorporate positive changes.

Displacement due to conflict or natural disaster does not stop women from becoming pregnant or giving birth; it is important that we support expectant mothers and babies during emergencies. Through our work, we hope to empower healthcare workers to enact small changes that can have a big impact.

Saving Lives by Saving a System

Endang W. Handzel

Endang holding a baby who, thanks to her team's work, survived a complicated delivery, Haiti 2013

The thing about being a surgeon is that results are immediate. When I was a practicing clinician, pregnant women would come to me, and thanks to my training, I knew exactly how to help. But I felt I could do more.

After the 2010 earthquake and cholera outbreak in Haiti, the high maternal mortality ratio was a clear sign that the public health system did not have the basic building blocks needed to provide care. One problem was keeping track of pregnant women. Many were giving birth in places with few or no trained attendants, while others died, trapped in their homes, far from the care they needed.

My team and I worked to train medical staff and began using social mapping to keep track of each pregnant woman and her needs. Understanding why women were dying allowed us to create a system that connects women with care. Over time, results from this work can touch many lives.

- Page last reviewed: August 15, 2016

- Page last updated: September 22, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir