FoodNet 2015 Preliminary Data

Documenting trends in foodborne illness—which illnesses are decreasing and which are increasing—is essential to the overall goal of reducing foodborne illness. Each year, FoodNet reports on the changes in the number of people in the United States sickened with foodborne infections from these pathogens that have been confirmed by laboratory tests. This “report card” also lets CDC, our partners, and policy makers know how much progress has been made in reducing foodborne illness.

This year’s report summarizes 2015 preliminary surveillance data and describes trends since 2012 for infections monitored by FoodNet—Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157 and non-O157, Shigella, Vibrio, Yersinia—and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS).

Key Findings

-

Tables & Figures

- In 2015, FoodNet received reports of 20,107 confirmed cases, 4,531 hospitalizations, and 77 deaths. FoodNet also received reports of 3,112 positive culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs) without culture-confirmation – a rate more than double that of 2012–2014.

- Compared with 2012–2014, the incidence of Cryptosporidium and non-O157 STEC infections was higher in 2015. These increases were likely driven by increases in diagnostic testing.

- Recent changes in diagnostic practices challenge our ability to find outbreaks and monitor disease trends. Some information about the bacteria causing infections, such as subtype and antimicrobial susceptibility, can only be obtained if a CIDT‐positive specimen is also cultured. Increasing use of CIDTs affects the interpretation of public health surveillance data and our ability to monitor progress toward achieving prevention goals.

- The most frequent causes of infection were Salmonella and Campylobacter, a finding that is consistent with previous years. Although Salmonella infections overall have shown little change since 2012-2014, infection with Salmonella serotype Typhimurium has decreased 15%.

Questions & Answers about the Report

What are culture-independent diagnostic tests? How are they affecting our ability to detect illnesses and track trends?

Culture independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs) work by detecting the presence of a specific antigen or genetic sequence of a germ. CIDTs do not require labs to grow a culture for isolation and identification of living organisms (also known as culturing). Consequently, these tests can be conducted more rapidly and yield results far sooner than can be done through traditional culturing methods.

Unlike cultures, CIDTs do not provide the information needed to characterize organisms that cause infections—information that is needed to find outbreaks and monitor disease trends. Measures can be taken to address this problem. Laboratories can culture specimens after a CIDT is positive (called “reflex culturing”), and CIDT manufacturers can create new tests to provide information that is now available only from cultured specimens.

Learn more about use of CIDTs for diagnosis of enteric infections >

Why are Cryptosporidium infections increasing?

Testing for Cryptosporidium has always been done using CIDTs, which are easier to use than traditional culture methods. Thus, the increasing incidence of Cryptosporidium infections might be due, in part, to more laboratories testing for these infections and, consequently, more infections being recognized.

In addition, Cryptosporidium infections have been increasing since 2005, the same year when a new drug, nitazoxanide, was approved to treat these infections. This same pattern has been seen throughout the country. The availability of this new treatment may have triggered more doctors to test patients for cryptosporidiosis and thus may partially explain the steady increase in infections that are diagnosed and reported.

Learn how to protect yourself from Cryptosporidium infections >

How are Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157 infections different from STEC non-O157 infections?

Both groups of infections have similar symptoms, which often include severe stomach cramps, diarrhea (often bloody), and vomiting. Symptoms vary for each person and can range from mild diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis to hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), a type of kidney failure. Here are some of the differences between O157 and non-O157:

- O157 is the most common type of STEC causing illness in the United States.

- Non-O157 STEC are a diverse group that includes all Shiga toxin-producing E. coli of serogroups other than O157. In the United States, most non-O157 strains isolated from humans belong to serogroups O26, O111, O103, O121, O45, and O145 (in order of frequency).

- Illnesses caused by STEC O157 are typically more severe than those caused by non-O157. For example, STEC O157 infections cause most cases of HUS.

- The most common sources of STEC O157 infection are beef and leafy vegetables. In contrast, a variety of foods have caused outbreaks of non-O157 STEC.

Why are STEC non-O157 infections increasing?

CIDTs, which are easier to use than traditional culture methods, are becoming widely used to diagnose STEC infections. The increasing incidence of non-O157 STEC infections might be due, in part, to more laboratories testing for Shiga toxin and, consequently, more non-O157 STEC infections being recognized.

Why has there been little change in the incidence of Salmonella infection overall?

Salmonella infection is a complicated problem because Salmonella has many sources, the sources vary by the type of Salmonella.

Many sources can spread Salmonella to people. Most food animals and many wild animals carry Salmonella in their intestines without getting sick. Most often, Salmonella bacteria are spread to people through contaminated food, including meat, poultry, and eggs; raw produce contaminated with animal or human fecal matter; and processed foods made with contaminated ingredients. People can also get Salmonella infection by drinking contaminated water and by having contact with animals or the places they live.

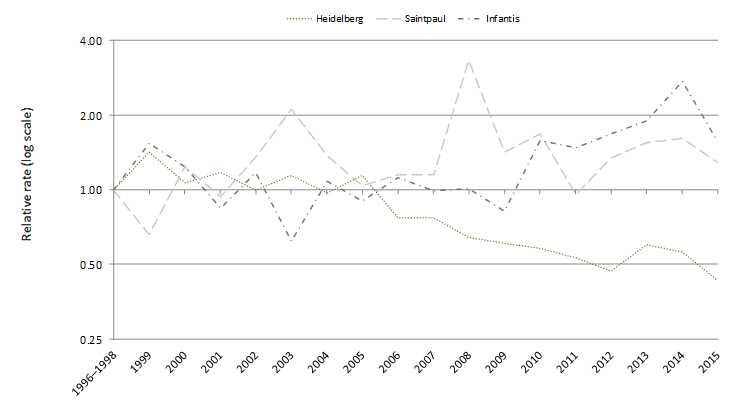

There are many different types of Salmonella bacteria (called serotypes) and the sources vary by serotype. The six most common serotypes reported to FoodNet in 2015 were Enteritidis, Newport, Typhimurium, Javiana, I 4,[5],12:i:-, and Poona. Some types of Salmonella are found mainly in one source (e.g., Heidelberg in chicken) and some are found in many food and wild animals (e.g., Typhimurium).

The particular interventions that work for each type of Salmonella may vary. To reduce incidence, we need interventions that target the types of Salmonella that are increasing or staying level. Work to decrease the incidence of Salmonella infection is ongoing. Whole genome sequencing is helping us better figure out the sources of people's illnesses, and FoodNet continues to track illnesses so we can see if prevention measures are working.

Why has there been a decrease in Salmonella Typhimurium?

Infections with S. Typhimurium have been decreasing for 20 years. The reasons are unclear. People get S. Typhimurium infection from a wide variety of food sources. Efforts by regulatory agencies and industry to make food safer might have contributed to the decrease in incidence. For example, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) has implemented many measures to decrease Salmonella contamination in beef and poultry. In addition, the poultry industry has increasingly used vaccines against Salmonella.

Questions & Answers about Food Safety

How does FoodNet contribute to food safety?

FoodNet provides a foundation of information needed to guide food safety policies and prevention efforts. FoodNet's surveillance data, such as those in this report, tell us where efforts are needed to reduce foodborne illnesses. FoodNet has been counting cases and tracking trends—which illnesses are decreasing and which are increasing—for infections transmitted commonly through food since 1996. Learn more >

What is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) doing to control and prevent foodborne disease?

CDC uses the best scientific methods and information available to monitor, investigate, control, and prevent foodborne illness. Using the tools of epidemiology and laboratory science, CDC proprovides scientific assessment of public health threats. CDC works closely with state health departments to monitor the frequency of specific diseases and conducts national surveillance for the diseases it monitors.

When food safety threats appear, CDC collaborates with public health partners, including state health departments, FDA, and USDA, to conduct epidemiologic and laboratory investigations to determine the causes of these threats and how they can be controlled. Although CDC does not regulate the safety of food, CDC works with regulatory agencies to inform food safety policies and assesses the effectiveness of current prevention efforts. CDC provides independent scientific assessment of what the problems are, how they can be controlled, and where gaps exist in our knowledge. You can find more information on foodborne illness and CDC’s prevention activities at CDC’s Food Safety website.

What are FDA, USDA, and other regulatory agencies doing to make food safer?

Government regulation related to food safety is the responsibility of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the United States Department of Agriculture's Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS), the National Marine Fisheries Service, and other regulatory agencies. CDC maintains regular contact with these regulatory agencies.

Regulatory agencies develop and implement measures to make food safer. Some recent measures by regulatory agencies and industry include:

- USDA-FSIS: Tighter standards for preventing Salmonella and Campylobacter contamination on ground chicken and turkey products, as well as raw chicken parts such as legs, wings, and breasts.

- FDA: New regulations to improve the safety of produce, processed foods, and imported foods.

- Chicken industry: Steps to decrease chicken contamination, including vaccinating chicken flocks against Salmonella.

Suggested citation: Huang JY, Henao OL, Griffin PM, Vugia DJ, Cronquist AB, Hurd S, Tobin-D'Angelo M, Ryan P, Smith K, Lathrop S, Zansky S, Cieslak PR, Dunn J, Holt KG, Wolpert B, Patrick ME; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Infection with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food and the Effect of Increasing Use of Culture-Independent Diagnostic Tests on Surveillance — Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2012–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 April 15:65:368-371

- Page last reviewed: March 17, 2016

- Page last updated: March 17, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir