FoodNet 2016 Preliminary Data

Documenting trends in foodborne illness—identifying which illnesses are decreasing and which are increasing—is essential to the overall goal of reducing foodborne illness. Each year, FoodNet reports on changes in the number of people in the United States sickened with infections from pathogens transmitted commonly through food. These pathogens have been detected by laboratory tests, including culture and culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs).

This year’s report summarizes 2016 preliminary surveillance data and describes trends since 2013 for infections monitored by FoodNet—Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, Yersinia—as well as cases of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) for 2015, the most recent year for which data are available.

Key Findings

View Tables & Figures

- In 2016, FoodNet received reports of 24,029 illnesses, 5,512 hospitalizations, and 98 deaths due to infections that were confirmed or CIDT-positive.

- The incidence of confirmed or CIDT-positive infections per 100,000 was highest for Campylobacter and Salmonella, which is consistent with previous years.

- The number of CIDT-positive reports is increasing. The number of Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia infections diagnosed by CIDT alone increased 114% in 2016 compared with the 2013–2015 average.

- Although CIDTs can provide timely information for clinical management of foodborne infections and are easier for laboratories to do, increasing use of CIDTs affects interpretation of public health surveillance data and our ability to monitor progress toward achieving prevention goals. It is difficult to interpret whether these are true changes in incidence or whether the change is in part or completely due to changes in diagnostic testing practices and procedures.

- Trends for some pathogens may be more affected than others by changes in use of CIDTs. Listeria infections, for which CIDTs have not previously been available, and cases of HUS, which do not rely on CIDT, did not change significantly in 2016 compared with the previous three years.

- Recent changes in diagnostic practices also challenge our ability to find outbreaks and monitor disease trends. Some information about the bacteria causing infections, such as subtype and antimicrobial susceptibility, can be obtained only if a CIDT-positive specimen is also cultured. FoodNet is gathering additional information to better understand the effect of CIDT on surveillance.

What are culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs)?

Culture independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs) work by detecting the presence of a specific antigen or genetic sequence of an organism. CIDTs do not require laboratories to grow a culture for isolation and identification of living organisms (also known as culturing). Consequently, these tests can be conducted more rapidly and yield results far sooner than can be done through traditional culturing methods.

Learn more about use of CIDTs for diagnosis of enteric infections >

How do CIDTs affect our ability to detect illnesses and track trends?

Unlike laboratory cultures, CIDTs do not provide certain information needed to characterize organisms that cause infections. For example, CIDTs currently can only detect Salmonella and not the Salmonella subtype. Laboratories can culture specimens after a CIDT is positive (called “reflex culturing”), and CIDT manufacturers can create new tests to provide information that is now available only from cultured specimens.

Learn more about use of CIDTs for diagnosis of enteric infections >

View presentations on the impact of CIDTs on diagnostics and surveillance >

What is FoodNet doing to be able to interpret trends?

CIDTs are counted and included in current FoodNet reports because they are increasingly used for diagnosis and likely represent true infections. However, more data are needed to understand how CIDTs have impacted trends in surveillance. FoodNet is working to collect data on the changes in number of people tested and test performance to account for these changes in trends.

Interpreting Changes in Incidence of Infections

Why do Cryptosporidium infections appear to be increasing?

Testing for Cryptosporidium has always been done using CIDTs, and these infections are considered confirmed. As more laboratories use CIDTs, they may be testing for Cryptosporidium more often, and, consequently, more infections may be being recognized.

Learn how to protect yourself from Cryptosporidium infections >

Why do STEC infections appear to be increasing?

Both the number of confirmed STEC infections and the number of confirmed or CIDT-positive STEC infections have increased, but the increase is twice as large when CIDT-positive infections are included. This increase may be due to the effect of how CIDTs identify STEC infections. CIDTs test for Shiga toxin, which does not provide the information needed to differentiate between STEC O157 and non-O157. As a result, many laboratories perform a reflex culture, leading to an increase in confirmed infections. When considering only confirmed infections, STEC non-O157 is increasing and STEC O157 shows no change. This increase in STEC non-O157 infections might be due, in part, to more laboratories using CIDTs for Shiga toxin and, consequently, more non-O157 STEC infections being recognized.

Why do Yersinia infections appear to be increasing?

Both the number of confirmed Yersinia infections and the number of confirmed or CIDT-positive Yersinia infections appear to be increasing, but the increase is three times as large when CIDT-positive infections are included. Yersinia is a difficult pathogen to culture. In the past, testing for this organism was limited and infections may have been underdiagnosed. CIDTs are easier to use than traditional culture methods and are becoming widely used to diagnose Yersinia infections. This increase in Yersinia infections might be due, in part, to more laboratories testing for Yersinia and more infections being recognized.

Are Campylobacter infections decreasing?

The number of confirmed Campylobacter infections appear to be decreasing, but when CIDT-positive infections are included, there appears to be no change. In contrast to other pathogens, most CIDT-positive Campylobacter infections do not receive a reflex culture, meaning we may have fewer confirmed cases. This is one example of why it is important to include CIDT-positive infections in trend data.

Learn how to protect yourself from Campylobacter infections >

Why does there appear to be little change in the overall incidence of Salmonella infection?

Laboratories often perform reflex cultures on CIDT-positive Salmonella infections. Even though most Salmonella infections are confirmed, interpreting trends is difficult because increasing use of CIDTs might mean more people are tested now than previously. FoodNet is working to collect the data needed to better understand the effect of CIDT on surveillance and trends. These reflex cultures also help protect the public’s health because they provide the information needed to characterize organisms, which can help identify and solve outbreaks.

Reducing the number of Salmonella infections is a complicated problem because Salmonella has many sources and the sources vary by the type of Salmonella.

Many sources can spread Salmonella to people. Most food animals and many wild animals carry Salmonella in their intestines without getting sick. Salmonella bacteria most often are spread to people through contaminated food, including meat, poultry, and eggs; raw produce contaminated with animal or human fecal matter; and processed foods made with contaminated ingredients. People also can get Salmonella infection by drinking contaminated water and by having contact with animals or the places they live.

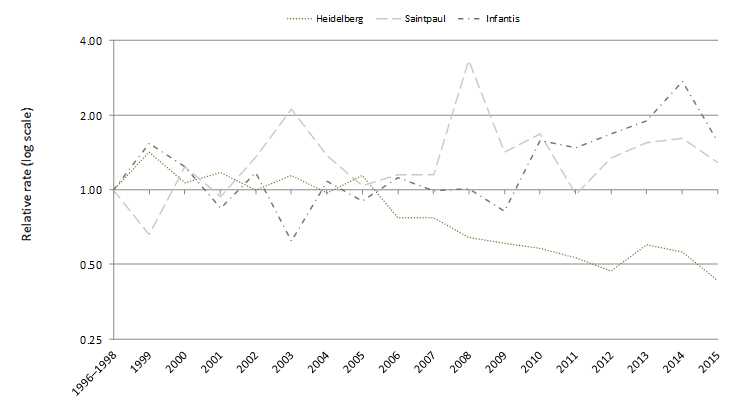

Many different serotypes (types) of Salmonella bacteria exist, and the sources vary by serotype. The 10 most common serotypes reported to FoodNet in 2016 were Enteritidis, Newport, Typhimurium, Javiana, I 4,[5],12:i:-, Infantis, Muenchen, Braenderup, Thompson, and Montevideo. Some types of Salmonella are found mainly in one source (for example, Heidelberg in chicken) and some are found in many food and wild animals (for example, Typhimurium).

The particular interventions that work for each type of Salmonella may vary. To reduce incidence, we need interventions that target the types of Salmonella that are increasing or staying the same. Work to decrease the incidence of Salmonella infection is ongoing. Whole genome sequencing is helping us better figure out the sources of people’s illnesses, and FoodNet continues to track illnesses so we can see if prevention measures are working.

Why does there appear to be a decrease in Salmonella Typhimurium?

Infections with S. Typhimurium have been decreasing for 20 years, long before CIDTs were used to diagnose foodborne infections, and the reasons for this decrease are unclear. Laboratories perform reflex culture on most CIDT-positive Salmonella infections, so it seems less likely that this decrease is due to changes in diagnostic testing. People get S. Typhimurium infection from a wide variety of food sources. Efforts by regulatory agencies and industry to make food safer might have contributed to this decrease in incidence. For example, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) has implemented many measures to decrease Salmonella contamination in beef and poultry. Also, the poultry industry has increasingly used vaccines against Salmonella in poultry flocks.

Questions & Answers About Food Safety

How does FoodNet contribute to food safety?

FoodNet provides a foundation for food safety policy and prevention efforts because FoodNet’s surveillance data, such as those in this report, tell us where efforts are needed to reduce the burden of foodborne illness. FoodNet has been counting cases and tracking trends—which illnesses are decreasing and which are increasing—for infections transmitted commonly through food since 1996. Learn more >

What is CDC doing to control and prevent foodborne disease?

CDC uses the best scientific methods and information available to monitor, investigate, control, and prevent foodborne illness. Using the tools of epidemiology and laboratory science, CDC provides scientific assessment of public health threats. CDC works closely with state health departments to monitor the frequency of specific diseases and conducts national surveillance for the diseases it monitors.

When food safety threats appear, CDC collaborates with public health partners, including state health departments, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and USDA, to conduct epidemiologic and laboratory investigations to determine the causes of these threats and how they can be controlled. Although CDC does not regulate the safety of food, CDC works with regulatory agencies to guide food safety policies and assess the effectiveness of current prevention efforts. CDC provides independent scientific assessment of what the problems are, how they can be controlled, and where gaps exist in our knowledge. You can find more information on foodborne illness and CDC’s prevention activities on CDC’s Food Safety website.

What are FDA, USDA, and other regulatory agencies doing to make food safer?

Government regulation related to food safety is the responsibility of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS), the National Marine Fisheries Service, and other regulatory agencies. CDC works closely with these regulatory agencies.

Regulatory agencies develop and implement measures to make food safer. Some recent measures by regulatory agencies and industry include:

- USDA-FSIS: Tighter standards for preventing Salmonella and Campylobacter contamination of ground chicken and turkey products, as well as raw chicken parts such as legs, wings, and breasts.

- FDA: Implementing the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) rules. The first major compliance date was on Sept. 19, 2016, for the preventive controls rules for human and animal food. Larger facilities producing human food must meet preventive controls and Current Good Manufacturing Practice requirements (CGMPs). Larger animal food facilities also must also meet CGMPs.

- Chicken industry: Steps to decrease chicken contamination, including vaccinating chicken flocks against Salmonella.

More Information

Suggested citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Incidence and Trends of Infection with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food and the Effect of Increasing Use of Culture-Independent Diagnostic Tests on Surveillance—Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2013–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 April 20.

- Page last reviewed: March 17, 2016

- Page last updated: March 17, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir