Rapid eye movement sleep

Rapid eye movement sleep (REM sleep or REMS) is a unique phase of sleep in mammals and birds, distinguishable by random/rapid movement of the eyes, accompanied with low muscle tone throughout the body, and the propensity of the sleeper to dream vividly.

The REM phase is also known as paradoxical sleep (PS) and sometimes desynchronized sleep because of physiological similarities to waking states, including rapid, low-voltage desynchronized brain waves. Electrical and chemical activity regulating this phase seems to originate in the brain stem and is characterized most notably by an abundance of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, combined with a nearly complete absence of monoamine neurotransmitters histamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine.

REM sleep is physiologically different from the other phases of sleep, which are collectively referred to as non-REM sleep (NREM sleep, NREMS, synchronized sleep). REM and non-REM sleep alternate within one sleep cycle, which lasts about 90 minutes in adult humans. As sleep cycles continue, they shift towards a higher proportion of REM sleep. The transition to REM sleep brings marked physical changes, beginning with electrical bursts called PGO waves originating in the brain stem. Organisms in REM sleep suspend central homeostasis, allowing large fluctuations in respiration, thermoregulation, and circulation which do not occur in any other modes of sleeping or waking. The body abruptly loses muscle tone, a state known as REM atonia.

Professor Nathaniel Kleitman and his student Eugene Aserinsky defined rapid eye movement and linked it to dreams in 1953. REM sleep was further described by researchers including William Dement and Michel Jouvet. Many experiments have involved awakening test subjects whenever they begin to enter the REM phase, thereby producing a state known as REM deprivation. Subjects allowed to sleep normally again usually experience a modest REM rebound. Techniques of neurosurgery, chemical injection, electroencephalography, positron emission tomography, and reports of dreamers upon waking, have all been used to study this phase of sleep.

Physiology

Electrical activity in the brain

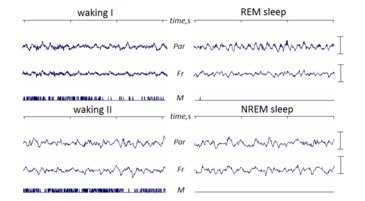

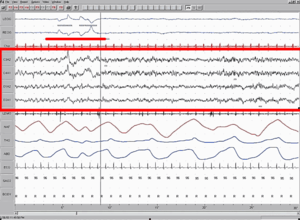

REM sleep is "paradoxical" because of its similarities to wakefulness. Although the body is paralyzed, the brain acts somewhat awake, with cerebral neurons firing with the same overall intensity as in wakefulness.[1][2] Electroencephalography during REM deep sleep reveal fast, low amplitude, desynchronized neural oscillation (brainwaves) that resemble the pattern seen during wakefulness which differ from the slow δ (delta) waves pattern of NREM deep sleep.[3][4] An important element of this contrast is the θ (theta) rhythm in the hippocampus[5] that show 40–60 Hz gamma waves, in the cortex, as it does in waking.[6] The cortical and thalamic neurons in the waking and REM sleeping brain are more depolarized (fire more readily) than in the NREM deep sleeping brain.[7]

During REM sleep, electrical connectivity among different parts of the brain manifests differently than during wakefulness. Frontal and posterior areas are less coherent in most frequencies, a fact which has been cited in relation to the chaotic experience of dreaming. However, the posterior areas are more coherent with each other; as are the right and left hemispheres of the brain, especially during lucid dreams.[8][9]

Brain energy use in REM sleep, as measured by oxygen and glucose metabolism, equals or exceeds energy use in waking. The rate in non-REM sleep is 11–40% lower.[10]

Brain stem

Neural activity during REM sleep seems to originate in the brain stem, especially the pontine tegmentum and locus coeruleus. REM sleep is punctuated and immediately preceded by PGO (ponto-geniculo-occipital) waves, bursts of electrical activity originating in the brain stem.[11] (PGO waves have long been measured directly in cats but not in humans because of constraints on experimentation; however comparable effects have been observed in humans during "phasic" events which occur during REM sleep, and the existence of similar PGO waves is thus inferred.)[9] These waves occur in clusters about every 6 seconds for 1–2 minutes during the transition from deep to paradoxical sleep.[4] They exhibit their highest amplitude upon moving into the visual cortex and are a cause of the "rapid eye movements" in paradoxical sleep.[12][13][10] Other muscles may also contract under the influence of these waves.[14]

Forebrain

Research in the 1990s using positron emission tomography (PET) confirmed the role of the brain stem and suggested that, within the forebrain, the limbic and paralimbic systems showed more activation than other areas.[1] The areas activated during REM sleep are approximately inverse to those activated during non-REM sleep[10] and display greater activity than in quiet waking. The "anterior paralimbic REM activation area" (APRA) includes areas linked with emotion, memory, fear and sex, and may thus relate to the experience of dreaming during REMS.[9][15] More recent PET research has indicated that the distribution of brain activity during REM sleep varies in correspondence with the type of activity seen in the prior period of wakefulness.[1]

The superior frontal gyrus, medial frontal areas, intraparietal sulcus, and superior parietal cortex, areas involved in sophisticated mental activity, show equal activity in REM sleep as in wakefulness. The amygdala is also active during REM sleep and may participate in generating the PGO waves, and experimental suppression of the amygdala results in less REM sleep.[16] The amygdala may also cardiac function in lieu of the less active insular cortex.[1]

Chemicals in the brain

Compared to slow-wave sleep, both waking and paradoxical sleep involve higher use of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which may cause the faster brainwaves. The monoamine neurotransmitters norepinephrine, serotonin and histamine are completely unavailable. Injections of acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, which effectively increases available acetylcholine, have been found to induce paradoxical sleep in humans and other animals already in slow-wave sleep. Carbachol, which mimics the effect of acetylcholine on neurons, has a similar influence. In waking humans, the same injections produce paradoxical sleep only if the monoamine neurotransmitters have already been depleted.[3][17][18][19][20]

Two other neurotransmitters, orexin and gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), seem to promote wakefulness, diminish during deep sleep, and inhibit paradoxical sleep.[3][21]

Unlike the abrupt transitions in electrical patterns, the chemical changes in the brain show continuous periodic oscillation.[22]

Models of REM regulation

According to the activation-synthesis hypothesis proposed by Robert McCarley and Allan Hobson in 1975–1977, control over REM sleep involves pathways of "REM-on" and "REM-off" neurons in the brain stem. REM-on neurons are primarily cholinergic (i.e., involve acetylcholine); REM-off neurons activate serotonin and noradrenaline, which among other functions suppress the REM-on neurons. McCarley and Hobson suggested that the REM-on neurons actually stimulate REM-off neurons, thereby serving as the mechanism for the cycling between REM and non-REM sleep.[3][17][19][23] They used Lotka–Volterra equations to describe this cyclical inverse relationship.[24] Kayuza Sakai and Michel Jouvet advanced a similar model in 1981.[21] Whereas acetylcholine manifests in the cortex equally during wakefulness and REM, it appears in higher concentrations in the brain stem during REM.[25] The withdrawal of orexin and GABA may cause the absence of the other excitatory neurotransmitters;[26] researchers in recent years increasingly include GABA regulation in their models.[27]

Eye movements

Most of the eye movements in “rapid eye movement” sleep are in fact less rapid than those normally exhibited by waking humans. They are also shorter in duration and more likely to loop back to their starting point. About seven of such loops take place over one minute of REM sleep. In slow-wave sleep the eyes can drift apart; however, the eyes of the paradoxical sleeper move in tandem.[28] These eye movements follow the ponto-geniculo-occipital waves originating in the brain stem.[12][13] The eye movements themselves may relate to the sense of vision experienced in the dream,[29] but a direct relationship remains to be clearly established. Congenitally blind people, who do not typically have visual imagery in their dreams, still move their eyes in REM sleep.[10] An alternative explanation suggests that the functional purpose of REM sleep is for procedural memory processing, and the rapid eye movement is only a side effect of the brain processing the eye-related procedural memory.[30][31]

Circulation, respiration, and thermoregulation

Generally speaking, the body suspends homeostasis during paradoxical sleep. Heart rate, cardiac pressure, cardiac output, arterial pressure, and breathing rate quickly become irregular when the body moves into REM sleep.[32] In general, respiratory reflexes such as response to hypoxia diminish. Overall, the brain exerts less control over breathing; electrical stimulation of respiration-linked brain areas does not influence the lungs, as it does during non-REM sleep and in waking.[33] The fluctuations of heart rate and arterial pressure tend to coincide with PGO waves and rapid eye movements, twitches, or sudden changes in breathing.[34]

Erections of the penis (nocturnal penile tumescence or NPT) normally accompany REM sleep in rats and humans.[35] If a male has erectile dysfunction (ED) while awake, but has NPT episodes during REM, it would suggest that the ED is from a psychological rather than a physiological cause. In females, erection of the clitoris (nocturnal clitoral tumescence or NCT) causes enlargement, with accompanying vaginal blood flow and transudation (i.e. lubrication). During a normal night of sleep the penis and clitoris may be erect for a total time of from one hour to as long as three and a half hours during REM.[36]

Body temperature is not well regulated during REM sleep, and thus organisms become more sensitive to temperatures outside their thermoneutral zone. Cats and other small furry mammals will shiver and breathe faster to regulate temperature during NREMS but not during REMS.[37] With the loss of muscle tone, animals lose the ability to regulate temperature through body movement. (However, even cats with pontine lesions preventing muscle atonia during REM did not regulate their temperature by shivering.)[38] Neurons which typically activate in response to cold temperatures—triggers for neural thermoregulation—simply do not fire during REM sleep, as they do in NREM sleep and waking.[39]

Consequently, hot or cold environmental temperatures can reduce the proportion of REM sleep, as well as amount of total sleep.[40][41] In other words, if at the end of a phase of deep sleep, the organism's thermal indicators fall outside of a certain range, it will not enter paradoxical sleep lest deregulation allow temperature to drift further from the desirable value.[42] This mechanism can be 'fooled' by artificially warming the brain.[43]

Muscle

REM atonia, an almost complete paralysis of the body, is accomplished through the inhibition of motor neurons. When the body shifts into REM sleep, motor neurons throughout the body undergo a process called hyperpolarization: their already-negative membrane potential decreases by another 2–10 millivolts, thereby raising the threshold which a stimulus must overcome to excite them. Muscle inhibition may result from unavailability of monoamine neurotransmitters (restraining the abundance of acetylcholine in the brainstem) and perhaps from mechanisms used in waking muscle inhibition.[44] The medulla oblongata, located between pons and spine, seems to have the capacity for organism-wide muscle inhibition.[45] Some localized twitching and reflexes can still occur.[46] Pupils contract.[14]

Lack of REM atonia causes REM behavior disorder, sufferers of which physically act out their dreams,[47] or conversely "dream out their acts", under an alternative theory on the relationship between muscle impulses during REM and associated mental imagery (which would also apply to people without the condition, except that commands to their muscles are suppressed).[48] This is different from conventional sleepwalking, which takes place during slow-wave sleep, not REM.[49] Narcolepsy by contrast seems to involve excessive and unwanted REM atonia—i.e., cataplexy and excessive daytime sleepiness while awake, hypnagogic hallucinations before entering slow-wave sleep, or sleep paralysis while waking.[50] Other psychiatric disorders including depression have been linked to disproportionate REM sleep.[51] Patients with suspected sleep disorders are typically evaluated by polysomnogram.[52][53]

Lesions of the pons to prevent atonia have induced functional “REM behavior disorder” in animals.[54]

Psychology

Dreaming

Rapid eye movement sleep (REM) has since its discovery been closely associated with dreaming. Waking up sleepers during a REM phase is a common experimental method for obtaining dream reports; 80% of neurotypical people can give some kind of dream report under these circumstances.[55][56] Sleepers awakened from REM tend to give longer, more narrative descriptions of the dreams they were experiencing, and to estimate the duration of their dreams as longer.[10][57] Lucid dreams are reported far more often in REM sleep.[58] (In fact these could be considered a hybrid state combining essential elements of REM sleep and waking consciousness.)[10] The mental events which occur during REM most commonly have dream hallmarks including narrative structure, convincingness (experiential resemblance to waking life), and incorporation of instinctual themes.[10] Sometimes they include elements of the dreamer's recent experience taken directly from episodic memory.[1] By one estimate, 80% of dreams occur during REM.[59]

Hobson and McCarley proposed that the PGO waves characteristic of “phasic” REM might supply the visual cortex and forebrain with electrical excitement which amplifies the hallucinatory aspects of dreaming.[18][23] However, people woken up during sleep do not report significantly more bizarre dreams during phasic REMS, compared to tonic REMS.[57] Another possible relationship between the two phenomena could be that the higher threshold for sensory interruption during REM sleep allows the brain to travel further along unrealistic and peculiar trains of thought.[57]

Some dreaming can take place during non-REM sleep. “Light sleepers” can experience dreaming during stage 2 non-REM sleep, whereas “deep sleepers”, upon awakening in the same stage, are more likely to report “thinking” but not “dreaming”. Certain scientific efforts to assess the uniquely bizarre nature of dreams experienced while asleep were forced to conclude that waking thought could be just as bizarre, especially in conditions of sensory deprivation.[57][60] Because of non-REM dreaming, some sleep researchers have strenuously contested the importance of connecting dreaming to the REM sleep phase. The prospect that well-known neurological aspects of REM do not themselves cause dreaming suggests the need to re-examine the neurobiology of dreaming per se.[61] Some researchers (Dement, Hobson, Jouvet, for example) tend to resist the idea of disconnecting dreaming from REM sleep.[10][62]

Creativity

After waking from REM sleep, the mind seems “hyperassociative”—more receptive to semantic priming effects. People awakened from REM have performed better on tasks like anagrams and creative problem solving.[63]

Sleep aids the process by which creativity forms associative elements into new combinations that are useful or meet some requirement.[64] This occurs in REM sleep rather than in NREM sleep.[65][66] Rather than being due to memory processes, this has been attributed to changes during REM sleep in cholinergic and noradrenergic neuromodulation.[65] High levels of acetylcholine in the hippocampus suppress feedback from hippocampus to the neocortex, while lower levels of acetylcholine and norepinephrine in the neocortex encourage the uncontrolled spread of associational activity within neocortical areas.[67] This is in contrast to waking consciousness, where higher levels of norepinephrine and acetylcholine inhibit recurrent connections in the neocortex. REM sleep through this process adds creativity by allowing "neocortical structures to reorganise associative hierarchies, in which information from the hippocampus would be reinterpreted in relation to previous semantic representations or nodes."[65]

Timing

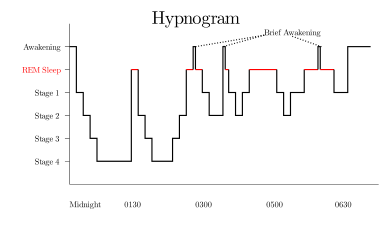

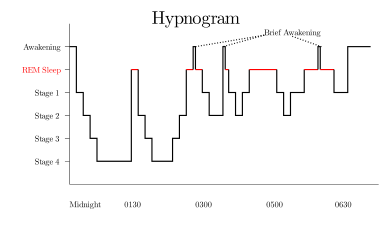

In the ultradian sleep cycle an organism alternates between deep sleep (slow, large, synchronized brain waves) and paradoxical sleep (faster, desynchronized waves). Sleep happens in the context of the larger circadian rhythm, which influences sleepiness and physiological factors based on timekeepers within the body. Sleep can be distributed throughout the day or clustered during one part of the rhythm: in nocturnal animals, during the day, and in diurnal animals, at night.[68] The organism returns to homeostatic regulation almost immediately after REM sleep ends.[69]

During a night of sleep, humans usually experience about four or five periods of REM sleep; they are shorter (~15 min) at the beginning of the night and longer (~25 min) toward the end. Many animals and some people tend to wake, or experience a period of very light sleep, for a short time immediately after a bout of REM. The relative amount of REM sleep varies considerably with age. A newborn baby spends more than 80% of total sleep time in REM.[70]

REM sleep typically occupies 20–25% of total sleep in adult humans: about 90–120 minutes of a night's sleep. The first REM episode occurs about 70 minutes after falling asleep. Cycles of about 90 minutes each follow, with each cycle including a larger proportion of REM sleep.[22] (The increased REM sleep later in the night is connected with the circadian rhythm and occurs even in people who didn't sleep in the first part of the night.)[71][72]

In the weeks after a human baby is born, as its nervous system matures, neural patterns in sleep begin to show a rhythm of REM and non-REM sleep. (In faster-developing mammals this process occurs in utero.)[73] Infants spend more time in REM sleep than adults. The proportion of REM sleep then decreases significantly in childhood. Older people tend to sleep less overall but sleep in REM for about the same absolute time, and therefore spend a greater proportion of sleep in REM.[74][59]

Rapid eye movement sleep can be subclassified into tonic and phasic modes.[75] Tonic REM is characterized by theta rhythms in the brain; phasic REM is characterized by PGO waves and actual “rapid” eye movements. Processing of external stimuli is heavily inhibited during phasic REM, and recent evidence suggests that sleepers are more difficult to arouse from phasic REM than in slow-wave sleep.[13]

Deprivation effects

Selective REMS deprivation causes a significant increase in the number of attempts to go into REM stage while asleep. On recovery nights, an individual will usually move to stage 3 and REM sleep more quickly and experience a REM rebound, which refers to an increase in the time spent in REM stage over normal levels. These findings are consistent with the idea that REM sleep is biologically necessary.[76][77] However, the "rebound" REM sleep usually does not last fully as long as the estimated length of the missed REM periods.[71]

After the deprivation is complete, mild psychological disturbances, such as anxiety, irritability, hallucinations, and difficulty concentrating may develop and appetite may increase. There are also positive consequences of REM deprivation. Some symptoms of depression are found to be suppressed by REM deprivation; aggression may increase, and eating behavior may get disrupted.[77][78] Higher norepinepherine is a possible cause of these results.[17] Whether and how long-term REM deprivation has psychological effects remains a matter of controversy. Several reports have indicated that REM deprivation increases aggression and sexual behavior in laboratory test animals.[77] Rats deprived of paradoxical sleep die in 4–6 weeks (twice the time before death in case of total sleep deprivation). Mean body temperature falls continually during this period.[72]

It has been suggested that acute REM sleep deprivation can improve certain types of depression when depression appears to be related to an imbalance of certain neurotransmitters. Although sleep deprivation in general annoys most of the population, it has repeatedly been shown to alleviate depression, albeit temporarily.[79] More than half the individuals who experience this relief report it to be rendered ineffective after sleeping the following night. Thus, researchers have devised methods such as altering the sleep schedule for a span of days following a REM deprivation period[80] and combining sleep-schedule alterations with pharmacotherapy[81] to prolong this effect. Antidepressants (including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclics, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors) and stimulants (such as amphetamine, methylphenidate and cocaine) interfere with REM sleep by stimulating the monoamine neurotransmitters which must be suppressed for REM sleep to occur. Administered at therapeutic doses, these drugs may stop REM sleep entirely for weeks or months. Withdrawal causes a REM rebound.[59][82] Sleep deprivation stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis much as antidepressants do, but whether this effect is driven by REM sleep in particular is unknown.[83]

In other animals

Although it manifests differently in different animals, REM sleep or something like it occurs in all land mammals as well as in birds. The primary criteria used to identify REM are the change in electrical activity, measured by EEG, and loss of muscle tone, interspersed with bouts of twitching in phasic REM.[85] The amount of REM sleep and cycling varies among animals; predators experience more REM sleep than prey.[17] Larger animals also tend to stay in REM for longer, possibly because higher thermal inertia of their brains and bodies allows them to tolerate longer suspension of thermoregulation.[86] The period (full cycle of REM and non-REM) lasts for about 90 minutes in humans, 22 minutes in cats, and 12 minutes in rats.[87] In utero, mammals spend more than half (50–80%) of a 24-hour day in REM sleep.[22]

Sleeping reptiles do not seem to have PGO waves or the localized brain activation seen in mammalian REM. However they do exhibit sleep cycles with phases of REM-like electrical activity measurable by EEG.[85] A recent study found periodic eye movements in the central bearded dragon of Australia, leading its authors to speculate that the common ancestor of amniotes may therefore have manifested some precursor to REMS.[88]

Sleep deprivation experiments on non-human animals can be set up differently than those on humans. The “flower pot” method involves placing a laboratory animal above water on a platform so small that it falls off upon losing muscle tone. The naturally rude awakening which results may elicit changes in the organism which necessarily exceed the simple absence of a sleep phase.[89] This method also stops working after about 3 days as the subjects (typically rats) lose their will to avoid the water.[72] Another method involves computer monitoring of brain waves, complete with automatic mechanized shaking of the cage when the test animal drifts into REM sleep.[90]

Possible functions

Some researchers argue that the perpetuation of a complex brain process such as REM sleep indicates that it serves an important function for the survival of mammalian and avian species. It fulfills important physiological needs vital for survival to the extent that prolonged REM sleep deprivation leads to death in experimental animals. In both humans and experimental animals, REM sleep loss leads to several behavioral and physiological abnormalities. Loss of REM sleep has been noticed during various natural and experimental infections. Survivability of the experimental animals decreases when REM sleep is totally attenuated during infection; this leads to the possibility that the quality and quantity of REM sleep is generally essential for normal body physiology.[91] Further, the existence of a "REM rebound" effect suggests the possibility of a biological need for REM sleep.

While the precise function of REM sleep is not well understood, several theories have been proposed.

Memory

Sleep in general aids memory. REM sleep may favor the preservation of certain types of memories: specifically, procedural memory, spatial memory, and emotional memory. In rats, REM sleep increases following intensive learning, especially several hours after, and sometimes for multiple nights. Experimental REM sleep deprivation has sometimes inhibited memory consolidation, especially regarding complex processes (e.g., how to escape from an elaborate maze).[92] In humans, the best evidence for REM's improvement of memory pertains to learning of procedures—new ways of moving the body (such as trampoline jumping), and new techniques of problem solving. REM deprivation seemed to impair declarative (i.e., factual) memory only in more complex cases, such as memories of longer stories.[93] REM sleep apparently counteracts attempts to suppress certain thoughts.[63]

According to the dual-process hypothesis of sleep and memory, the two major phases of sleep correspond to different types of memory. “Night half” studies have tested this hypothesis with memory tasks either begun before sleep and assessed in the middle of the night, or begun in the middle of the night and assessed in the morning.[94] Slow-wave sleep, part of non-REM sleep, appears to be important for declarative memory. Artificial enhancement of the non-REM sleep improves the next-day recall of memorized pairs of words.[95] Tucker et al. demonstrated that a daytime nap containing solely non-REM sleep enhances declarative memory but not procedural memory.[96] According to the sequential hypothesis the two types of sleep work together to consolidate memory.[97]

Sleep researcher Jerome Siegel has observed that extreme REM deprivation does not significantly interfere with memory. One case study of an individual who had little or no REM sleep due to a shrapnel injury to the brainstem did not find the individual's memory to be impaired. Antidepressants, which suppress REM sleep, show no evidence of impairing memory and may improve it.[82]

Graeme Mitchison and Francis Crick proposed in 1983 that by virtue of its inherent spontaneous activity, the function of REM sleep "is to remove certain undesirable modes of interaction in networks of cells in the cerebral cortex", which process they characterize as "unlearning". As a result, those memories which are relevant (whose underlying neuronal substrate is strong enough to withstand such spontaneous, chaotic activation) are further strengthened, whilst weaker, transient, "noise" memory traces disintegrate.[98] Memory consolidation during paradoxical sleep is specifically correlated with the periods of rapid eye movement, which do not occur continuously. One explanation for this correlation is that the PGO electrical waves, which precede the eye movements, also influence memory.[12] REM sleep could provide a unique opportunity for “unlearning” to occur in the basic neural networks involved in homeostasis, which are protected from this "synaptic downscaling" effect during deep sleep.[99]

Neural ontogeny

REM sleep prevails most after birth, and diminishes with age. According to the "ontogenetic hypothesis", REM (also known in neonates as active sleep) aids the developing brain by providing the neural stimulation that newborns need to form mature neural connections.[100] Sleep deprivation studies have shown that deprivation early in life can result in behavioral problems, permanent sleep disruption, and decreased brain mass.[101][73] The strongest evidence for the ontogenetic hypothesis comes from experiments on REM deprivation and the development of the visual system in the lateral geniculate nucleus and primary visual cortex.[73]

Defensive immobilization

Ioannis Tsoukalas of Stockholm University has hypothesized that REM sleep is an evolutionary transformation of a well-known defensive mechanism, the tonic immobility reflex. This reflex, also known as animal hypnosis or death feigning, functions as the last line of defense against an attacking predator and consists of the total immobilization of the animal so that it appears dead. Tsoukalas argues that the neurophysiology and phenomenology of this reaction shows striking similarities to REM sleep; for example, both reactions exhibit brainstem control, paralysis, hypocampal theta rhythm, and thermoregulatory changes.[102][103]

Shift of gaze

According to "scanning hypothesis", the directional properties of REM sleep are related to a shift of gaze in dream imagery. Against this hypothesis is that such eye movements occur in those born blind and in fetuses in spite of lack of vision. Also, binocular REMs are non-conjugated (i.e., the two eyes do not point in the same direction at a time) and so lack a fixation point. In support of this theory, research finds that in goal-oriented dreams, eye gaze is directed towards the dream action, determined from correlations in the eye and body movements of REM sleep behavior disorder patients who enact their dreams.[104]

Oxygen supply to cornea

Dr. David M. Maurice (1922-2002), an eye specialist and semi-retired adjunct professor at Columbia University, proposed that REM sleep was associated with oxygen supply to the cornea, and that aqueous humor, the liquid between cornea and iris, was stagnant if not stirred.[105] Among the supportive evidences, he calculated that if aqueous humor was stagnant, oxygen from iris had to reach cornea by diffusion through aqueous humor, which was not sufficient. According to the theory, when the animal is awake, eye movement (or cool environmental temperature) enables the aqueous humor to circulate. When the animal is sleeping, REM provides the much-needed stir to aqueous humor. This theory is consistent with the observation that fetuses, as well as eye-sealed newborn animals, spend much time in REM sleep, and that during a normal sleep, a person's REM sleep episodes become progressively longer deeper into the night. However, owls have REM sleep, but do not move their head more than in non-REM sleep[106] and is well known that owls' eyes are nearly immobile.[107]

Other theories

Another theory suggests that monoamine shutdown is required so that the monoamine receptors in the brain can recover to regain full sensitivity.

The sentinel hypothesis of REM sleep was put forward by Frederick Snyder in 1966. It is based upon the observation that REM sleep in several mammals (the rat, the hedgehog, the rabbit, and the rhesus monkey) is followed by a brief awakening. This does not occur for either cats or humans, although humans are more likely to wake from REM sleep than from NREM sleep. Snyder hypothesized that REM sleep activates an animal periodically, to scan the environment for possible predators. This hypothesis does not explain the muscle paralysis of REM sleep; however, a logical analysis might suggest that the muscle paralysis exists to prevent the animal from fully waking up unnecessarily, and allowing it to return easily to deeper sleep.[108][109][110]

Jim Horne, a sleep researcher at Loughborough University, has suggested that REM in modern humans compensates for the reduced need for wakeful food foraging.[6]

Other theories are that REM sleep warms the brain, stimulates and stabilizes the neural circuits that have not been activated during waking, or creates internal stimulation to aid development of the CNS; while some argue that REM lacks any purpose, and simply results from random brain activation.[104][111]

Discovery and further research

Recognition of different types of sleep can be seen in the literature of ancient India and Rome. Observers have long noticed that sleeping dogs twitch and move but only at certain times.[112]

The German scientist Richard Klaue in 1937 first discovered a period of fast electrical activity in the brains of sleeping cats. In 1944, Ohlmeyer reported 90-minute ultradian sleep cycles involving male erections lasting for 25 minutes.[113] At University of Chicago in 1952, Eugene Aserinsky, Nathaniel Kleitman, and William C. Dement, discovered phases of rapid eye movement during sleep, and connected these to dreaming. Their article was published September 10, 1953.[114] Aserinsky, then Kleitman, first observed the eye movements and accompanying neuroelectrical activity in their own children.[112][115]

William Dement advanced the study of REM deprivation, with experiments in which subjects were awoken every time their EEG indicated the beginning of REM sleep. He published "The Effect of Dream Deprivation" in June 1960.[116] ("REM deprivation" has become the more common term following subsequent research indicating the possibility of non-REM dreaming.)

Neurosurgical experiments by Michel Jouvet and others in the following two decades added an understanding of atonia and suggested the importance of the pontine tegmentum (dorsolateral pons) in enabling and regulating paradoxical sleep.[17] Jouvet and others found that damaging the reticular formation of the brainstem inhibited this type of sleep.[45] Jouvet coined the name "paradoxical sleep" in 1959 and in 1962 published results indicating that it could occur in a cat with its entire forebrain removed.[21][111][14] The mechanisms of muscle atonia was initially proposed by Horace Winchell Magoun in 1940s and later confirmed by Rodolfo Llinás in 1960s.[117]

Hiroki R. Ueda and his colleagues identified muscarinic receptor genes M1 (Chrm1) and M3 (Chrm3) as essential genes for REMS sleep.[118]

See also

References

- Luca Matarazzo, Ariane Foret, Laura Mascetti, Vincenzo Muto, Anahita Shaffii, & Pierre Maquet, "A systems-level approach to human REM sleep"; in Mallick et al, eds. (2011).

- Myers, David (2004). Psychology (7th ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-7167-8595-8. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- Ritchie E. Brown & Robert W. McCarley (2008), "Neuroanatomical and neurochemical basis of wakefulness and REM sleep systems", in Neurochemistry of Sleep and Wakefulness ed. Monti et al.

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), "Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §1.2 (pp. 7–23).

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), "Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §7.2–3 (pp. 206–208).

- Jim Horne (2013), “Why REM sleep? Clues beyond the laboratory in a more challenging world”, Biological Psychology 92.

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), "Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §8.1 (pp. 232–243).

- Jayne Gackenbach, “Interhemispheric EEG Coherence in REM Sleep and Meditation: The Lucid Dreaming Connection” in Antrobus & Bertini (eds.), The Neuropsychology of Sleep and Dreaming.

- Edward F. Pace-Schott, "REM sleep and dreaming", in Mallick et al, eds. (2011).

- J. Alan Hobson, Edward F. Pace-Scott, & Robert Stickgold (2000), “Dreaming and the brain: Toward a cognitive neuroscience of conscious states”, Behavioral and Brain Sciences 23.

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), "Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §9.1–2 (pp. 263–282).

- Subimal Datta (1999), "PGO Wave Generation: Mechanism and functional significance", in Rapid Eye Movement Sleep ed. Mallick & Inoué.

- Ummehan Ermis, Karsten Krakow, & Ursula Voss (2010), “Arousal thresholds during human tonic and phasic REM sleep”, Journal of Sleep Research 19.

- Siegel, Jerome M. (2009). "The Neurobiology of Sleep". Seminars in Neurology 29(4). doi:10.1055/s-0029-1237118.

- Nofzinger, Eric A., et al. (1997). "Forebrain activation in REM sleep: an FDG PET study". Brain Research 770:192–201.

- Larry D. Sanford & Richard J. Ross, "Amygdalar regulation of REM sleep"; in Mallick et al. (2011).

- Birendra N. Mallick, Vibha Madan, & Sushil K. Jha (2008), "Rapid eye movement sleep regulation by modulation of the noradrenergic system", in Neurochemistry of Sleep and Wakefulness ed. Monti et al.

- Hobson JA (2009). "REM sleep and dreaming: towards a theory of protoconsciousness". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10 (11): 803–813. doi:10.1038/nrn2716. PMID 19794431.

- Aston-Jones G., Gonzalez M., & Doran S. (2007). "Role of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in arousal and circadian regulation of the sleep-wake cycle." Ch. 6 in Brain Norepinephrine: Neurobiology and Therapeutics. G.A. Ordway, M.A. Schwartz, & A. Frazer, eds. Cambridge UP. 157–195. Accessed 21 Jul. 2010. Academicdepartments.musc.edu Archived 2011-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Siegel J.M. (2005). "REM Sleep." Ch. 10 in Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 4th ed. M.H. Kryger, T. Roth, & W.C. Dement, eds. Elsevier. 120–135.

- Pierre-Hervé Luppi et al. (2008), "Gamma-aminobutyric acid and the regulation of paradoxical, or rapid eye movement, sleep", in Neurochemistry of Sleep and Wakefulness ed. Monti et al.

- Robert W. McCarley (2007), “Neurobiology of REM and NREM sleep”, Sleep Medicine 8.

- J. Alan Hobson & Robert W. McCarley, “The Brain as a Dream-State Generator: An Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis of the Dream Process”, American Journal of Psychiatry 134.12, December 1977.

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §12.2 (pp. 369–373).

- Ralph Lydic & Helen A. Baghdoyan, "Acetylcholine modulates sleep and wakefulness: a synaptic perspective", in Neurochemistry of Sleep and Wakefulness ed. Monti et al.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 16.

- James T. McKenna, Lichao Chen, & Robert McCarley, "Neuronal models of REM-sleep control: evolving concepts"; in Mallick et al. (2011).

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §10.7.2 (pp. 307–309).

- Andrillon, Thomas; et al. (2015). "Single neuron activity and eye movements during human REM sleep and awake vision". Nature Communications. 6 (1038): 7884. doi:10.1038/ncomms8884. PMC 4866865. PMID 26262924.

- Zhang, Jie (2005). Continual-activation theory of dreaming, Dynamical Psychology.

- Zhang, Jie (2016). Towards a comprehensive model of human memory, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.2103.9606.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 12–15.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 22–27.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 35–37

- Jouvet (1999), The Paradox of Sleep, pp. 169–173.

- Brown et al. (2012), “Control of Sleep and Wakefulness”, p. 1127.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 12–13.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, pp. 46–47.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, pp. 51–52.

- Ronald Szymusiak, Md. Noor Alam, & Dennis McGinty (1999), "Thermoregulatory Control of the NonREM-REM Sleep Cycle", in Rapid Eye Movement Sleep ed. Mallick & Inoué.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, pp. 57–59.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 45. “Therefore, it appears that the onset of REM sleep requires the inactivation of the central thermostat in late NREM sleep. However, only a restricted range of preoptic-hypothalamic temperatures at the end of NREM sleep is compatible with REM sleep onset. This range may be considered a sort of temperature gate for REM sleep, that is constrained in width more at low than at neutral ambient temperature.”

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 61. “On the other hand, a balance between opposing ambient and preoptic-anterior hypothalamic thermal loads influencing peripheral and central thermoreceptors, respectively, may be experimentally achieved so as to promote sleep. In particular, warming of the preoptic-anterior hypothalamic region in a cold environment hastens REM sleep onset and increases its duration (Parmeggiana et al., 1974, 1980; Sakaguchi et al., 1979).”

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §10.8–9 (pp. 309–324).

- Yuan-Yang Lai & Jerome M. Siegel (1999), "Muscle Atonia in REM Sleep", in Rapid Eye Movement Sleep ed. Mallick & Inoué.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 17. “In other words, the functional controls requiring high hierarchical levels of integration are the most affected during REM sleep, whereas reflex activity is only altered but not obliterated.”

- Lapierre O, Montplaisir J (1992). "Polysomnographic features of REM sleep behavior disorder: development of a scoring method". Neurology. 42 (7): 1371–4. doi:10.1212/wnl.42.7.1371. PMID 1620348.

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §13.3.2.3 (pp. 428–432).

- Jouvet (1999), The Paradox of Sleep, p. 102.

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §13.1 (pp. 396–400).

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §13.2 (pp. 400–415).

- Koval'zon VM (Jul–Aug 2011). "[Central mechanisms of sleep-wakefulness cycle]". Fiziologiia Cheloveka. 37 (4): 124–34. PMID 21950094.

- "[Polysomnography]". Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 87. “The open-loop mode of physiological regulation in REM sleep may restore the efficiency of the different neuronal networks of the brain stem by expressing also genetically coded patterns of instinctive behavior that are kept normally hidden from view by skeletal muscle atonia. Such behaviorally concealed neuronal activity was demonstrated by the effects of experimental lesions of specific pontine structures (Hendricks, 1982; Hendricks et al., 1977, 1982; Henley and Morrison, 1974; Jouvet and Delorme, 1965; Sastre and Jouvet, 1979; Villablanca, 1996). Not only was the skeletal muscle atonia suppressed by also motor fragments of complex instinctive behaviors appeared, such as walking and attack, that were not externally motivated (see Morrison, 2005).”

- Solms (1997), The Neuropsychology of Dreams, pp. 10, 34.

- Edward F. Pace-Schott, "REM sleep and dreaming", in Mallick et al, eds. (2011), p. 8. "A meta-analysis of 29 awakening studies by Nielsen (2000) revealed that about 82% of awakenings from REM result in recall of a dream whereas this frequency following NREM awakenings is lower at 42%."

- Ruth Reinsel, John Antrobus, & Miriam Wollman (1992), “Bizarreness in Dreams and Waking Fantasy”, in Antrobus & Bertini (eds.), The Neuropsychology of Sleep and Dreaming.

- Stephen LaBerge (1992), “Physiological Studies of Lucid Dreaming”, in Antrobus & Bertini (eds.), The Neuropsychology of Sleep and Dreaming.

- Dmitri Markov, Marina Goldman, & Karl Doghramji (2012). "Normal Sleep and Circadian Rhythms: Neurobiological Mechanisms Underlying Sleep and Wakefulness". Sleep Medicine Clinics 7(3), September 2012. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2012.06.015.

- Delphine Ouidette et al. (2012), “Dreaming without REM sleep”, Consciousness and Cognition 21.

- Solms (1997), The Neuropsychology of Dreams, Chapter 6: “The Problem of REM Sleep” (pp. 54–57).”

- Jouvet (1999), The Paradox of Sleep, p. 104. “I frankly support the theory that we do not dream all night, as do William Dement and Alan Hobson and most neurophysiologists. I am rather surprised that publications about dream recall during slow wave sleep increase in number each year. Further, the classic distinction established in the 1960s between 'poor' dream recall, devoid of color and detail, during slow wave sleep, and 'rich' recall, full of color and detail, during paradoxical sleep, is beginning to disappear. I believe that dream recall during slow wave sleep could be recall from previous paradoxical sleep.”

- Rasch & Born (2013), “About Sleep's Role in Memory”, p. 688.

- Wagner U, Gais S, Haider H, Verleger R, Born J (2004). "Sleep inspires insight". Nature. 427 (6972): 352–5. doi:10.1038/nature02223. PMID 14737168.

- Cai DJ, Mednick SA, Harrison EM, Kanady JC, Mednick SC (2009). "REM, not incubation, improves creativity by priming associative networks". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106 (25): 10130–10134. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900271106. PMC 2700890. PMID 19506253.

- Walker MP, Liston C, Hobson JA, Stickgold R (November 2002). "Cognitive flexibility across the sleep-wake cycle: REM-sleep enhancement of anagram problem solving". Brain Research. Cognitive Brain Research. 14 (3): 317–24. doi:10.1016/S0926-6410(02)00134-9. PMID 12421655.

- Hasselmo ME (September 1999). "Neuromodulation: acetylcholine and memory consolidation". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 3 (9): 351–359. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01365-0. PMID 10461198.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 9–11.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 17.

- Van Cauter E, Leproult R, Plat L (2000). "Age-related changes in slow wave sleep and REM sleep and relationship with growth hormone and cortisol levels in healthy men". JAMA. 284 (7): 861–8. doi:10.1001/jama.284.7.861. PMID 10938176.

- Daniel Aeschbach, "REM-sleep regulation: circadian, homeostatic, and non-REM sleep-dependent determinants"; in Mallick et al. (2011).

- Nishidh Barot & Clete Kushida, "Significance of deprivation studies"; in Mallick et al. (2011).

- Marcos G. Frank, "The ontogeny and function(s) of REM sleep", in Mallick et al, eds. (2011).

- Kazuo Mishima, Tetsuo Shimizu, & Yasuo Hishikawa (1999), "REM Sleep Across Age and Sex", in Rapid Eye Movement Sleep ed. Mallick & Inoué.

- Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W (2000). Principles & Practices of Sleep Medicine. WB Saunders Company. pp. 1, 572.

- Endo T, Roth C, Landolt HP, Werth E, Aeschbach D, Achermann P, Borbély AA (1998). "Selective REM sleep deprivation in humans: Effects on sleep and sleep EEG". The American Journal of Physiology. 274 (4 Pt 2): R1186–R1194. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.4.R1186. PMID 9575987.

- Steven J. Ellman, Arthur J. Spielman, Dana Luck, Solomon S. Steiner, & Ronnie Halperin (1991), "REM Deprivation: A Review", in The Mind in Sleep, ed. Ellman & Antrobus.

- "Types of Sleep Deprivation". Archived from the original on 2013-07-05.

- Ringel BL, Szuba MP (2001). "Potential mechanisms of the sleep therapies for depression". Depression and Anxiety. 14 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1002/da.1044. PMID 11568980.

- Riemann D, König A, Hohagen F, Kiemen A, Voderholzer U, Backhaus J, Bunz J, Wesiack B, Hermle L, Berger M (1999). "How to preserve the antidepressive effect of sleep deprivation: A comparison of sleep phase advance and sleep phase delay". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 249 (5): 231–237. doi:10.1007/s004060050092. PMID 10591988.

- Wirz-Justice A, Van den Hoofdakker RH (1999). "Sleep deprivation in depression: What do we know, where do we go?". Biological Psychiatry. 46 (4): 445–453. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00125-0. PMID 10459393.

- Jerome M. Siegel (2001). "The REM Sleep-Memory Consolidation Hypothesis Archived 2010-09-13 at the Wayback Machine". Science Vol. 294.

- Grassi Zucconi G, Cipriani S, Balgkouranidou I, Scattoni R (2006). "'One night' sleep deprivation stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis". Brain Research Bulletin. 69 (4): 375–381. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.01.009. PMID 16624668.

- Lesku, J. A.; Meyer, L. C. R.; Fuller, A.; Maloney, S. K.; Dell'Omo, G.; Vyssotski, A. L.; Rattenborg, N. C. (2011). Balaban, Evan (ed.). "Ostriches Sleep like Platypuses". PLoS ONE. 6 (8): e23203. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023203. PMC 3160860. PMID 21887239.

- Niels C. Rattenborg, John A. Lesku, and Dolores Martinez-Gonzalez, "Evolutionary perspectives on the function of REM sleep", in Mallick et al, eds. (2011).

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, pp. 13, 59–61. “In species with different body mass (e.g., rats, rabbits, cats, humans) the average duration of REM sleep episodes increases with the increase in body and brain weight, a determinant of the thermal inertia. Such inertia delays the changes in body core temperature so alarming as to elicit arousal from REM sleep. In addition, other factors, such as fur, food, and predator–prey relationships influencing REM sleep duration out to be mentioned here.”

- Steriade & McCarley (1990), Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep", §12.1 (p. 363).

- Shein-Idelson, Mark; Ondracek, Janie M.; Liaw, Hua-Peng; Reiter, Sam; Laurent, Gilles (2016-04-29). "Slow waves, sharp waves, ripples, and REM in sleeping dragons". Science. 352 (6285): 590–595. doi:10.1126/science.aaf3621. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27126045.

- Rasch & Born (2013), “About Sleep's Role in Memory”, p. 686–687.

- Feng Pingfu; Ma Yuxian; Vogel Gerald W (2001). "Ontogeny of REM Rebound in Postnatal Rats". Sleep. 24 (6): 645–653. doi:10.1093/sleep/24.6.645. PMID 11560177.

- Robert P. Vertes (1986), "A Life-Sustaining Function for REM Sleep: A Theory", Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews 10.

- Rasch & Born (2013), “About Sleep's Role in Memory”, p. 686. Deprivation of REM sleep (mostly without simultaneous sleep recording) appeared to primarily impair memory for- mation on complex tasks, like two-way shuttle box avoidance and complex mazes, which encompass a change in the animals regular repertoire (69, 100, 312, 516, 525, 539, 644, 710, 713, 714, 787, 900, 903–906, 992, 1021, 1072, 1111, 1113, 1238, 1352, 1353). In contrast, long-term memory for simpler tasks, like one-way active avoidance and simple mazes, were less consistently affected (15, 249, 386, 390, 495, 558, 611, 644, 821, 872, 902, 907–909, 1072, 1091, 1334).”

- Rasch & Born (2013), “About Sleep's Role in Memory”, p. 687.

- Rasch & Born (2013), “About Sleep's Role in Memory”, p. 689. “The dual process hypothesis assumes that different sleep stages serve the consolidation of different types of memories (428, 765, 967, 1096). Specifically it has been assumed that declarative memory profits from SWS, whereas the consolidation of nondeclarative memory is supported by REM sleep.” This hypothesis received support mainly from studies in humans, particularly from those employing the 'night half paradigm.'”

- Marshall L, Helgadóttir H, Mölle M, Born J (2006). "Boosting slow oscillations during sleep potentiates memory". Nature. 444 (7119): 610–3. doi:10.1038/nature05278. PMID 17086200.

- Tucker MA, Hirota Y, Wamsley EJ, Lau H, Chaklader A, Fishbein W (2006). "A daytime nap containing solely non-REM sleep enhances declarative but not procedural memory" (PDF). Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 86 (2): 241–7. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2006.03.005. PMID 16647282. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- Rasch & Born (2013), “About Sleep's Role in Memory”, p. 690–691.

- Crick F, Mitchison G (1983). "The function of dream sleep". Nature. 304 (5922): 111–14. doi:10.1038/304111a0. PMID 6866101.

- Parmeggiani (2011), Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep, p. 89. “In contrast to NREM sleep, downscaling of synapses would be produced in REM sleep by random bursts of neuronal firing (e.g., also bursts underlying ponto-geniculo-occipital waves) (see Tonioni and Cirelli, 2005). / This hypothesis is particularly enriched in functional significance by considering at this point the opposite nature, homeostatic and poikilostatic, of the systemic neural regulation of physiological functions in these sleep states. The important fact is that homeostasis if fully preserved in NREM sleep. This means that a systemic synaptic downcaling (slow-wave electroencephalographic activity) is practically limited to the relatively homogenous cortical structures of the telencephalon, while the whole brain stem, from diencephalon to medulla, is still exerting its basic functions of integrated homeostatic regulation of both somatic and autonomic physiological functions. In REM sleep, however, the necessary synaptic downscaling in the brain stem is instead the result of random neuronal firing.”

- Marks et al. 1994

- Mirmiran M, Scholtens J, van de Poll NE, Uylings HB, van der Gugten J, Boer GJ (1983). "Effects of experimental suppression of active (REM) sleep during early development upon adult brain and behavior in the rat". Brain Res. 283 (2–3): 277–86. doi:10.1016/0165-3806(83)90184-0. PMID 6850353.

- Tsoukalas I (2012). "The origin of REM sleep: A hypothesis". Dreaming. 22 (4): 253–283. doi:10.1037/a0030790.

- Vitelli, R. (2013). “Exploring the Mystery of REM Sleep”. Psychology Today, On-line, March 25

- Leclair-Visonneau L, Oudiette D, Gaymard B, Leu-Semenescu S, Arnulf I (2010). "Do the eyes scan dream images during rapid eye movement sleep? Evidence from the rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder model". Brain. 133 (6): 1737–46. doi:10.1093/brain/awq110. PMID 20478849.

- Maurice, David (1998). "The Von Sallmann Lecture 1996: An Ophthalmological Explanation of REM Sleep" (PDF). Experimental Eye Research. 66 (2): 139–145. doi:10.1006/exer.1997.0444. PMID 9533840.

- Madeleine Scriba; Anne-Lyse Ducrest; Isabelle Henry; Alexei L Vyssotski; Niels C Rattenborg; Alexandre Roulin (2013). "Linking melanism to brain development: expression of a melanism-related gene in barn owl feather follicles covaries with sleep ontogeny". Frontiers in Zoology. 10 (42): 42. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-10-42. PMC 3734112. PMID 23886007.; see Fig. S1

- Steinbach, M. J. (2004). "Owls' eyes move". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 88 (8): 1103. doi:10.1136/bjo.2004.042291. PMC 1772283. PMID 15258042.

- Steven J. Ellman; John S. Antrobus (1991). "Effects of REM deprivation". The Mind in Sleep: Psychology and Psychophysiology. John Wiley and Sons. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-471-52556-1.

- Jouvet (1999), The Paradox of Sleep, pp. 122–124.

- William H. Moorcroft; Paula Belcher (2003). "Functions of REMS and Dreaming". Understanding Sleep and sDreaming. Springer. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-306-47425-5.

- Perrine M. Ruby (2011), “Experimental research on dreaming: state of the art and neuropsychoanalytic perspectives”, Frontiers in Psychology 2.

- Adrian R. Morrison, "The Discovery of REM sleep: the death knell of the passive theory of sleep", in Mallick et al, eds. (2011).

- Jouvet (1999), The Paradox of Sleep, p. 32.

- Aserinsky E, Kleitman N (1953). "Regularly Occurring Periods of Eye Motility, and Concomitant Phenomena, during Sleep". Science. 118 (3062): 273–274. doi:10.1126/science.118.3062.273. PMID 13089671.

- Eugene Aserinsky, "The discovery of REM sleep". Journal of the History of Neuroscience 5(3), 1996. doi:10.1080/09647049609525671

- William Dement, “The Effect of Dream Deprivation: The need for a certain amount of dreaming each night is suggested by recent experiments.” Science 131.3415, 10 June 1960.

- Llinas, R.; Terzuolo, C. A. (1964). "Mechanisms of Supraspinal Actions Upon Spinal Cord Activities. Reticular Inhibitory Mechanisms on Alpha-Extensor Motoneurons". Journal of Neurophysiology. 27 (4): 579–591. doi:10.1152/jn.1964.27.4.579. ISSN 0022-3077. PMID 14194959.

- Niwa Y, Kanda GN, Yamada RG, Shi S, Sunagawa GA, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Fujishima H, Matsumoto N, Masumoto KH, Nagano M, Kasukawa T, Galloway J, Perrin D, Shigeyoshi Y, Ukai H, Kiyonari H, Sumiyama K, Ueda HR (2018). "Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors Chrm1 and Chrm3 Are Essential for REM Sleep". Cell Reports. 24 (9): 2231–2247.e7. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.082. ISSN 2211-1247. PMID 30157420.

Sources

- Antrobus, John S., & Mario Bertini (1992). The Neuropsychology of Sleep and Dreaming. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-0925-2

- Brown Ritchie E.; Basheer Radhika; McKenna James T.; Strecker Robert E.; McCarley Robert W. (2012). "Control of Sleep and Wakefulness". Physiological Reviews. 92 (3): 1087–1187. doi:10.1152/physrev.00032.2011. PMC 3621793. PMID 22811426.

- Ellman, Steven J., & Antrobus, John S. (1991). The Mind in Sleep: Psychology and Psychophysiology. Second edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-52556-1

- Jouvet, Michel (1999). The Paradox of Sleep: The Story of Dreaming. Originally Le Sommeil et le Rêve, 1993. Translated by Laurence Garey. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-10080-0

- Mallick, B. N., & S. Inoué (1999). Rapid Eye Movement Sleep. New Delhi: Narosa Publishing House; distributed in the Americas, Europe, Australia, & Japan by Marcel Dekker Inc (New York).

- Mallick, B. N.; S. R. Pandi-Perumal; Robert W. McCarley; and Adrian R. Morrison. Rapid Eye Movement Sleep: Regulation and Function. Cambridge University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-521-11680-0

- Monti, Jaime M., S. R. Pandi-Perumal, & Christopher M. Sinton (2008). Neurochemistry of Sleep and Wakefulness. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86441-1

- Parmeggiani, Pier Luigi (2011). Systemic Homeostasis and Poikilostasis in Sleep: Is REM Sleep a Physiological Paradox? London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-94916-572-2

- Rasch, Björn, & Jan Born (2013). “About Sleep's Role in Memory”. Physiological Reviews 93, pp. 681–766.

- Solms, Mark (1997). The Neuropsychology of Dreams: A Clinico-Anatomical Study. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; ISBN 0-8058-1585-6

- Steriade, Mircea, & Robert W. McCarley (1990). Brainstem Control of Wakefulness and Sleep. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-43342-7

Further reading

- Snyder F (1966). "Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Dreaming". American Journal of Psychiatry. 123 (2): 121–142. doi:10.1176/ajp.123.2.121. PMID 5329927.

- Edward F. Pace-Schott, ed. (2003). Sleep and Dreaming: Scientific Advances and Reconsiderations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00869-3.

- Koulack, D. To Catch A Dream: Explorations of Dreaming. New York, SUNY, 1991.

- Nguyen TQ, Liang CL, Marks GA (2013). "GABA(A) receptors implicated in REM sleep control express a benzodiazepine binding site". Brain Res. 1527: 131–40. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2013.06.037. PMC 3839793. PMID 23835499.

- Liang CL, Marks GA (2014). "GABAA receptors are located in cholinergic terminals in the nucleus pontis oralis of the rat: implications for REM sleep control". Brain Res. 1543: 58–64. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2013.10.019. PMID 24141149.

- Grace KP, Vanstone LE, Horner RL (2014). "Endogenous Cholinergic Input to the Pontine REM Sleep Generator Is Not Required for REM Sleep to Occur". J. Neurosci. 34 (43): 14198–209. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0274-14.2014. PMC 6608391. PMID 25339734.

- Carson III, Culley C., Kirby, Roger S., Goldstein, Irwin, editors, "Textbook of Erectile Dysfunction" Oxford, U.K.; Isis Medical Media, Ltd., 1999; Moreland, R.B. & Nehra, A.; Pathosphysiology of erectile dysfunction; a molecular basis, role of NPT in maintaining potency: pp. 105–15.

External links

| Look up rapid eye movement sleep in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- PBS' NOVA episode "What Are Dreams?" Video and Transcript

- LSDBase - an open sleep research database with images of REM sleep recordings.