Sleep debt

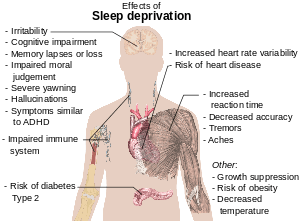

Sleep debt or sleep deficit is the cumulative effect of not getting enough sleep. A large sleep debt may lead to mental or physical fatigue.

There are two kinds of sleep debt: the results of partial sleep deprivation and total sleep deprivation. Partial sleep deprivation occurs when a person or a lab animal sleeps too little for several days or weeks. Total sleep deprivation means being kept awake for at least 24 hours. There is debate in the scientific community over the specifics of sleep debt, and it is not considered to be a disorder.

Phosphorylation of proteins

It has been found that there are 80 proteins in the brain, called "sleep need index phosphoproteins" (SNIPPs), which become more and more phosphorylated during waking hours, and are dephosphorylated during sleep. The phosphorylation is aided by a protein called Sik3. There is a kind of mutant mouse called Sleepy with a mutated version of this protein (called SLEEPY) which is more active than the normal version, resulting in the mice being constantly sleepy and showing more slow-wave activity during non-REM sleep, which is the best measurable index of sleep need known. Inhibiting Sik3 decreases phosphorylation and slow-wave activity in both normal and mutant mice.[2][3]

Scientific debate

There is debate among researchers as to whether the concept of sleep debt describes a measurable phenomenon. The September 2004 issue of the journal Sleep contains dueling editorials from two leading sleep researchers, David F. Dinges[4] and Jim Horne.[5] A 1997 experiment conducted by psychiatrists at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine suggested that cumulative nocturnal sleep debt affects daytime sleepiness, particularly on the first, second, sixth, and seventh days of sleep restriction.[6]

In one study, subjects were tested using the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT). Different groups of people were tested with different sleep times for two weeks: 8 hours, 6 hours, 4 hours, and total sleep deprivation. Each day they were tested for the number of lapses on the PVT. The results showed that as time went by, each group's performance worsened, with no sign of any stopping point. Moderate sleep deprivation was found to be detrimental; people who slept 6 hours a night for 10 days had similar results to those who were completely sleep deprived for 1 day.[7][8]

Evaluation

Sleep debt has been tested in a number of studies through the use of a sleep onset latency test.[9] This test attempts to measure how easily a person can fall asleep. When this test is done several times during a day, it is called a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT). The subject is told to go to sleep and is awakened after determining the amount of time it took to fall asleep. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), an eight item questionnaire with scores ranging from 0 to 24, is another tool used to screen for potential sleep debt.

A January 2007 study from Washington University in St. Louis suggests that saliva tests of the enzyme amylase could be used to indicate sleep debt, as the enzyme increases its activity in correlation with the length of time a subject has been deprived of sleep.[10][11]

The control of wakefulness has been found to be strongly influenced by the protein orexin. A 2009 study from Washington University in St. Louis has illuminated important connections between sleep debt, orexin, and amyloid beta, with the suggestion that the development of Alzheimer's disease could hypothetically be a result of chronic sleep debt or excessive periods of wakefulness.[12]

References

- Reference list is found on image page in Commons: Commons:File:Effects of sleep deprivation.svg#References

- Wang, Zhiqiang; et al. (Jun 13, 2018). "Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of the molecular substrates of sleep need". Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0218-8. PMC 6350790.

- "Chemical clock tracks our need for sleep". New Scientist. Jun 23, 2018.

- Dinges, DF (September 2004). "Sleep debt and scientific evidence". Sleep. 27 (6): 1050–2. PMID 15532196.

- Horne, Jim (September 2004). "Is there a sleep debt?". Sleep. 27 (6): 1047–9. PMID 15532195.

- Dinges DF, Pack F, Williams K, et al. (April 1997). "Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4–5 hours per night". Sleep. 20 (4): 267–77. PMID 9231952.

- Walker, M.P. (2009, October 21). *Sleep Deprivation III: Brain consequences – Attention, concentration and real life.* Lecture given in Psychology 133 at the University of California, Berkeley, CA.

- Knutson, Kristen L.; Spiegel, Karine; Penev, Plamen; Van Cauter, Eve (June 2007). "The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 11 (3): 163–178. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002. PMC 1991337. PMID 17442599.

- Klerman EB, Dijk DJ (October 2005). "Interindividual variation in sleep duration and its association with sleep debt in young adults". Sleep. 28 (10): 1253–9. PMC 1351048. PMID 16295210.

- Fisher, Mark. "Sleeping well isn't easy, but it doesn't have to be hard either". supplementyoursleep.com. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "First Biomarker for Human Sleepiness Identified", Record of Washington University in St. Louis, January 25, 2007

- J.E. Kang, M.M. Lim, R.J. Bateman, J.J. Lee, L.P. Smyth, J.R. Cirrito, N. Fujiki, S. Nishino and D.M. Holtzman (2009). "Amyloid-{beta} Dynamics Are Regulated by Orexin and the Sleep-Wake Cycle". Science. 326 (5955): 1005–7. doi:10.1126/science.1180962. PMC 2789838. PMID 19779148.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Dement, William C., MD, PhD "The Promise of Sleep.", Delacorte Press, Random House Inc., New York, 1999.

External links

- Harvard Magazine article, "Deep into Sleep"

- Lost Sleep Can't Be Made Up, Study Suggests – LiveScience