Macular telangiectasia

Macular telangiectasia describes two distinct retinal diseases affecting the macula of the eye, macular telangiectasia type 1 and macular telangiectasia type 2.[1]

| Macular telangiectasia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Macular telangiectasia | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Macular telangiectasia (MacTel) type 1 is a very rare disease, typically unilateral and usually affecting male patients. MacTel type 2 is more frequent than type 1 and generally affects both eyes (bilateral). It usually affects both sexes equally. Both types of MacTel should not be confused with Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), from which it can be distinguished by symptoms, clinical features, pathogenesis, and disease management. However, both AMD and MacTel eventually lead to (photoreceptor) atrophy and thus loss of central vision.

The etiology of both types of MacTel is still unknown and no treatment has been found to be effective to prevent further progression. Because lost photoreceptors cannot be recovered, early diagnosis and treatment appear to be essential to prevent loss of visual function. Several centers are currently trying to find new diagnostics and treatments to understand the causes and biochemical reactions in order to halt or counteract the adverse effects.

Contemporary research has shown that MacTel type 2 is likely a neurodegenerative disease with secondary changes of the blood vessels of the macula.[1] Although MacTel type 2 has been previously regarded as a rare disease, it is in fact probably much more common than previously thought. The very subtle nature of the early findings in MacTel mean the diagnoses are often missed by optometrists and general ophthalmologists. Due to increased research activity since 2005, many new insights have been gained into this condition since its first description by Dr. J. Donald Gass in 1982.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with idiopathic macular telangiectasia type 1 are typically 40 years of age or older. They may have a coincident history of ischemic vascular diseases such as diabetes or hypertension, but these do not appear to be causative factors.

Macular telangiectasia type 2 usually present first between the ages of 50 and 60 years, with a mean age of 55–59 years. They may present with a wide range of visual impact, from totally asymptomatic to substantially impaired; in most cases however, patients retain functional acuity of 20/200 or better. Metamorphopsia may be a subjective complaint. Due to the development of paracentral scotomota (blind spots), reading ability is impaired early in the disease course. It might be even the first symptom of the disease.[2]

The condition may remain stable for extended periods, sometimes interspersed with sudden decreases in vision. Patients’ loss of visual function is disproportionately worse than the impairment of their visual acuity, which is only mildly affected in many cases. In patients with MacTel, as compared with a reference population, there is a significantly higher prevalence of systemic conditions associated with vascular disease, including history of hypertension, history of diabetes, and history of coronary disease. MacTel does not cause total blindness, yet it commonly causes gradual loss of the central vision required for reading and driving.

Cause

Familial transmission is now recognized in a small proportion of people with MacTel type 2; however, the nature of any related genetic defect or defects remains elusive. The MacTel genetic study team hopes that exome analysis in the affected population and relatives may be more successful in identifying related variants.

Pathophysiology

Macular telangiectasia type 1

Probably best defined as an acquired capillary ectasia (i.e., a focal expansion or outpouching) and dilation in the parafoveal region, leading to vascular incompetence. The telangiectatic vessels develop micro-aneurysms, which subsequently leak fluid, blood, and occasionally, lipid. Some have described Macular telangiectasia type 1 as a variant of Coats' disease, which is defined by extensive peripheral retinal telangiectasis, exudative retinal detachment, relatively young age of onset, and male predilection. While the precise etiology is unknown, it has been speculated that chronic venous congestion caused by obstruction of the retinal veins as they cross retinal arteries at the horizontal raphe may be a contributory factor.

Macular telangiectasia type 2

Histopathology studies have shown a loss of Mueller cell markers in the clinically altered area,[3] suggesting that Mueller cell death may be involved in the pathogenesis. One animal model in which the receptor for very low density lipoproteins is “knocked out” mimics many of the clinical characteristics of the disease and other models are being developed in the laboratories. Animal studies using the established model have shown an anti-oxidant diet and a special form of gene therapy to be effective in preserving visual function in these mice.

Diagnosis

Although a variety of complex classification schemes are described in the literature, there are essentially two forms of macular telangiectasia: type 1 and type 2. Type 1 is typically unilateral and occurs almost exclusively in males after the age of 40. Type 2 is mostly bilateral, occurring equally in males and females.

Macular telangiectasia type 1

In this group, lipid exudate is common, while pigment plaques and retinal crystals are rare.

Macular telangiectasia type 2

Although MacTel is uncommon, its prevalence is probably higher than most physicians believe. The early findings are subtle, so the diagnosis is likely often missed by optometrists and general ophthalmologists. MacTel was detected in 0.1% of subjects in the Beaver Dam study population over age 45 years,[4] but this is probably an underestimate because identification was made based only on color photographs.

No major new biomicroscopic features of MacTel have been identified since the early work of Gass and colleagues.[1] The advent of optical coherence tomography (OCT) has allowed better characterization of the nature of the inner and outer lamellar cavities. Loss of central masking seen on autofluorescence studies, apparently due to loss of luteal pigment, is now recognized as probably the earliest and most sensitive and specific MacTel abnormality.

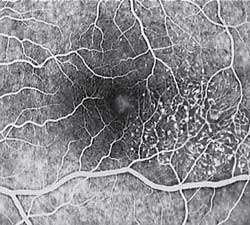

The key fundus findings in macular telangiectasia type 2 involve retinal crystalline—fine, refractile deposits in the superficial retinal layers—may be seen within the affected area, a focal area of diminished retinal transparency (i.e., "greying") and/or small retinal hemorrhages just temporal to the fovea. Dilated capillaries may also be noted within this area, and while this is often difficult to visualize ophthalmoscopically, the abnormal capillary pattern is readily identifiable with fluorescein angiography. Areas of focal RPE hyperplasia, i.e., pigment plaques, often develop in the paramacular region as a response to these abnormal vessels. Other signs of macular telangiectasia type 2 include right angle venules, representing an unusual alteration of the vasculature in the paramacular area, with vessels taking an abrupt turn toward the macula as if being dragged.

Diagnosis of MacTel type 2 may be aided by the use of advanced imaging techniques such as fluorescein angiography, fundus autofluorescence, and OCT. These can help to identify the abnormal vessels, pigment plaques, retinal crystals, foveal atrophy and intraretinal cavities associated with this disorder.

Fluorescein angiography (FA) is helpful in identifying the anomalous vasculature, particularly in the early stages of Type 2 disease. Formerly, FA was essential in making a definitive diagnosis. However, the diagnosis can be established with less invasive imaging techniques such as OCT and fundus autofluorescence. Some clinicians argue that FA testing may be unnecessary when a diagnosis is apparent via less invasive means.

The natural history of macular telangiectasia suggests a slowly progressive disorder. A retrospective series of 20 patients over 10 to 21 years showed deterioration of vision in more than 84% of eyes, either due to intra-retinal edema and serous retinal detachment (Type 1) or pigmented RPE scar formation or neovascularisation (Type 2).

Differential diagnosis

Macular telangiectasia type 1 must be differentiated from secondary telangiectasis caused by retinal vascular diseases such as retinal venous occlusions, diabetic retinopathy, radiation retinopathy, sickle cell maculopathy, inflammatory retinopathy/Irvine–Gass syndrome, ocular ischemic syndrome/carotid artery obstruction, hypertensive retinopathy, polycythemia vera retinopathy, and localized retinal capillary hemangioma. In addition, Macular telangiectasia type 1 should be clearly differentiated from dilated perifoveal capillaries with evidence of vitreous cellular infiltration secondary to acquired inflammatory disease or tapetoretinal dystrophy. Less commonly, macular telangiectasis has been described in association with fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, incontinentia pigmenti, and familial exudative vitreoretinopathy with posterior pole involvement.

Macular telangiectasia type 2 is commonly under-diagnosed. The findings may appear very similar to diabetic retinopathy, and many cases have been incorrectly ascribed to diabetic retinopathy or age-related macular degeneration. Recognition of this condition can save an affected patient from unnecessarily undergoing extensive medical testing and/or treatment. MacTel should be considered in cases of mild paramacular dot and blot hemorrhages and in cases of macular and paramacular RPE hyperplasia where no other cause can be identified.

Treatment

The most crucial aspect of managing patients with macular telangiectasia is recognition of the clinical signs. This condition is relatively uncommon: hence, many practitioners may not be familiar with or experienced in diagnosing the disorder. MacTel must be part of the differential in any case of idiopathic paramacular hemorrhage, vasculopathy, macular edema or focal pigment hypertrophy, especially in those patients without a history of retinopathy or contributory systemic disease.

Treatment options for macular telangiectasia type 1 include laser photocoagulation, intra-vitreal injections of steroids, or anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents. Photocoagulation was recommended by Gass and remains to date the mainstay of treatment. It seems to be successful in causing resolution of exudation and VA improvement or stabilization in selected patients. Photocoagulation should be used sparingly to reduce the chance of producing a symptomatic paracentral scotoma and metamorphopsia. Small burns (100–200 μm) of moderate intensity in a grid-pattern and on multiple occasions, if necessary, are recommended. It is unnecessary to destroy every dilated capillary, and, particularly during the initial session of photocoagulation, those on the edge of the capillary-free zone should be avoided.

Intravitreal injections of triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA) which have proved to be beneficial in the treatment of macular edema by their anti-inflammatory effect, their downregulation of VEGF production, and stabilization of the blood retinal barrier were reported anecdotally in the management of macular telangiectasia type 1. In two case reports, IVTA of 4 mg allowed a transitory reduction of retinal edema, with variable or no increase in VA. As expected with all IVTA injections, the edema recurred within 3–6 months, and no permanent improvement could be shown.14,15 In general, the effect of IVTA is short-lived and complications, mainly increased intraocular pressure and cataract, limit its use.

Indocyanine green angiography-guided laser photocoagulation directed at the leaky microaneurysms and vessels combined with sub-Tenon’s capsule injection of triamcinolone acetonide has also been reported in a limited number of patients with macular telangiectasia type 1 with improvement or stabilization of vision after a mean follow-up of 10 months.16 Further studies are needed to assess the efficacy of this treatment modality.

Recently, intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents, namely bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeted against pro-angiogenic, circulatory VEGF, and ranibizumab, a FDA-approved monoclonal antibody fragment that targets all VEGF-A isoforms, have shown improved visual outcome and reduced leakage in macular edema form diabetes and retinal venous occlusions. In one reported patient with macular telangiectasia type 1, a single intravitreal bevacizumab injection resulted in a marked increase in VA from 20/50 to 20/20, with significant and sustained decrease in both leakage on FA and cystoid macular edema on OCT up to 12 months. It is likely that patients with macular telangiectasia type 1 with pronounced macular edema from leaky telangiectasis may benefit functionally and morphologically from intravitreal anti-VEGF injections, but this warrants further studies.

Today, laser photocoagulation remains mostly effective, but the optimal treatment of macular telangiectasia type 1 is questioned, and larger series comparing different treatment modalities seem warranted. The rarity of the disease however, makes it difficult to assess in a controlled randomized manner.

However, these treatment modalities should be considered only in cases of marked and rapid vision loss secondary to macular edema or CNV. Otherwise, a conservative approach is recommended, since many of these patients will stabilize without intervention.

Macular telangiectasia type 2

To date, there is no known effective treatment for the non-proliferative form of macular telangiectasia type 2. Treatment options are limited. No treatment has to date been shown to prevent progression. The variable course of progression of the disease makes it difficult to assess the efficacy of treatments. Retinal laser photocoagulation is not helpful. In fact, laser therapy may actually enhance vessel ectasia and promote intraretinal fibrosis in these individuals. It is hoped that a better understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease may lead to better treatments.

The use of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors, which have proven so successful in treating age-related macular degeneration, have not proven to be effective in non-proliferative MacTel type 2.[5] Ranibizumab reduces the vascular leak seen on angiography, although microperimetry suggests that neural atrophy may still proceed in treated eyes. In proliferative stages (neovascularisation), treatment with Anti-VEGF can be helpful.

CNTF is believed to have neuroprotective properties and could thus be able to slow down the progression of MacTel type 2. It has been shown to be safe to use in MacTel patients in a phase 1 safety trial.[6]

Terminology

MacTel type 2 may also be referred to by various names, including (idiopathic) juxtafoveolar, perifoveal or parafoveal telangiectasis, depending on the source. All refer to the same disease.

References

- Charbel Issa, Peter; Gillies, Mark C.; Chew, Emily Y.; Bird, Alan C.; Heeren, Tjebo F.C.; Peto, Tunde; Holz, Frank G.; Scholl, Hendrik P.N. (2013). "Macular telangiectasia type 2". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 34: 49–77. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.11.002. PMC 3638089. PMID 23219692.

- Heeren, Tjebo F. C.; Holz, Frank G.; Issa, Peter Charbel (2014). "First Symptoms and Their Age of Onset in Macular Telangiectasia Type 2". Retina. 34 (5): 916–9. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000082. PMID 24351446.

- Powner, Michael B.; Gillies, Mark C.; Tretiach, Marina; Scott, Andrew; Guymer, Robyn H.; Hageman, Gregory S.; Fruttiger, Marcus (2010). "Perifoveal Müller Cell Depletion in a Case of Macular Telangiectasia Type 2". Ophthalmology. 117 (12): 2407–16. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.04.001. PMC 2974049. PMID 20678804.

- Klein, Ronald; Blodi, Barbara A.; Meuer, Stacy M.; Myers, Chelsea E.; Chew, Emily Y.; Klein, Barbara E.K. (2010). "The Prevalence of Macular Telangiectasia Type 2 in the Beaver Dam Eye Study". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 150 (1): 55–62.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2010.02.013. PMC 2901890. PMID 20609708.

- Charbel Issa, Peter; Finger, Robert P.; Kruse, Kathrin; Baumüller, Sönke; Scholl, Hendrik P.N.; Holz, Frank G. (2011). "Monthly Ranibizumab for Nonproliferative Macular Telangiectasia Type 2: A 12-Month Prospective Study". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 151 (5): 876–886.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2010.11.019. PMID 21334595.

- Chew, Emily Y.; Clemons, Traci E.; Peto, Tunde; Sallo, Ferenc B.; Ingerman, Avner; Tao, Weng; Singerman, Lawrence; Schwartz, Steven D.; Peachey, Neal S.; Bird, Alan C. (2015). "Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor for Macular Telangiectasia Type 2: Results from a Phase 1 Safety Trial". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 159 (4): 659–666.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2014.12.013. PMC 4361328. PMID 25528956.