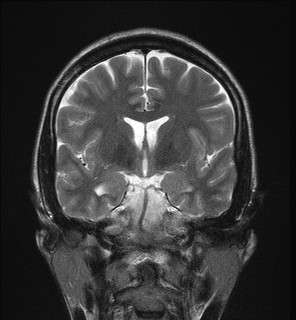

Hippocampal sclerosis

Hippocampal sclerosis (HS) is a neuropathological condition with severe neuronal cell loss and gliosis in the hippocampus, specifically in the CA-1 (Cornu Ammonis area 1) and subiculum of the hippocampus. It was first described in 1880 by Wilhelm Sommer.[1] Hippocampal sclerosis is a frequent pathologic finding in community-based dementia. Hippocampal sclerosis can be detected with autopsy or MRI. Individuals with hippocampal sclerosis have similar initial symptoms and rates of dementia progression to those with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and therefore are frequently misclassified as having Alzheimer's Disease. But clinical and pathologic findings suggest that hippocampal sclerosis has characteristics of a progressive disorder although the underlying cause remains elusive.[2] A diagnosis of hippocampal sclerosis has a significant effect on the life of patients because of the notable mortality, morbidity and social impact related to epilepsy, as well as side effects associated with antiepileptic treatments.[3]

| Hippocampal sclerosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mesial Temporal Sclerosis | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Symptoms

Histopathological hallmarks of hippocampal sclerosis include segmental loss of pyramidal neurons, granule cell dispersion and reactive gliosis. This means that pyramidal neuronal cells are lost, granule cells are spread widely or driven off, and glial cells are changed in response to damage to the central nervous system (CNS). Generally, hippocampal sclerosis may be seen in some cases of epilepsy. It is important to clarify the nature of insults that most likely have caused the hippocampal sclerosis and have initiated the epileptogenic process.[4] Presence of hippocampal sclerosis and duration of epilepsy longer than 10 years were found to cause parasympathetic autonomic dysfunction, whereas seizure refractoriness was found to cause sympathetic autonomic dysfunction. Apart from its association with the chronic nature of epilepsy, hippocampal sclerosis was shown to have an important role in internal cardiac autonomic dysfunction. Patients with left hippocampal sclerosis had more severe parasympathetic dysfunction as compared with those with right hippocampal sclerosis.[5] In young individuals, mesial temporal sclerosis is commonly recognized with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). On the other hand, it is an often unrecognized cause of cognitive decline, typically presenting with severe memory loss.[6]

Temporal lobe epilepsy

Ammon's horn (or hippocampal) sclerosis (AHS) is the most common type of neuropathological damage seen in individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy.[7] This type of neuron cell loss, primarily in the hippocampus, can be observed in approximately 65% of people suffering from this form of epilepsy. Sclerotic hippocampus is pointed to as the most likely origin of chronic seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy patients, rather than the amygdala or other temporal lobe regions.[8] Although hippocampal sclerosis has been identified as a distinctive feature of the pathology associated with temporal lobe epilepsy, this disorder is not merely a consequence of prolonged seizures as argued.[8] A long and ongoing debate addresses the issue of whether hippocampal sclerosis is the cause or the consequence of chronic and pharmaceutically resistant seizure activity. Temporal lobectomy is a common treatment for TLE, surgically removing the seizure focal area, though complications can be severe.[9]

Other variants of temporal lobe epilepsy include mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE),[10] MTLE due to hippocampal sclerosis,[11] thalamic changes in temporal lobe epilepsy with and without hippocampal sclerosis,[12] and hippocampal sclerosis with and without mesial temporal lobe epilepsy.[10]

Causes

Aging

Although hippocampal sclerosis is relatively commonly found among elderly people (≈10% of individuals over the age of 85 years), association between this disease and ageing remains unknown.[13]

Vascular risk factors

There were also observations that hippocampal sclerosis was associated with vascular risk factors. Hippocampal sclerosis cases were more likely than Alzheimer's disease to have had a history of stroke (56% vs. 25%) or hypertension (56% vs. 40%), evidence of small vessel disease (25% vs. 6%), but less likely to have had diabetes mellitus (0% vs. 22%).[6]

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic correlates of health have been well established in the study of heart disease, lung cancer, and diabetes. Many of the explanations for the increased incidence of these conditions in people with lower socioeconomic status (SES) suggest they are the result of poor diet, low levels of exercise, dangerous jobs (exposure to toxins etc.) and increased levels of smoking and alcohol intake in socially deprived populations. Hesdorffer et al. found that low SES, indexed by poor education and lack of home ownership, was a risk factor for epilepsy in adults, but not in children in a population study.[14] Low socioeconomic status may have a cumulative effect for the risk of developing epilepsy over a lifetime.[15]

Diagnosis

Classification

Mesial temporal sclerosis is a specific pattern of hippocampal neuron cell loss.[16][17] There are 3 specific patterns of cell loss. Cell loss might involve sectors CA1 and CA4, CA4 alone, or CA1 to CA4.[17] Associated hippocampal atrophy and gliosis is common.[16] MRI scan commonly displays increased T2 signal and hippocampal atrophy.[16] Mesial temporal sclerosis might occur with other temporal lobe abnormalities (dual pathology).[16] Mesial temporal sclerosis is the most common pathological abnormality in temporal lobe epilepsy.[16][17] It has been linked to abnormalities in TDP-43.[18]

Treatment

References

- Sommer, W (1880). "Erkrankung des Ammon's horn als aetiologis ches moment der epilepsien". Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 10 (3): 631–675. doi:10.1007/BF02224538.

- Leverenz, JB; Agustin, CM; Tsuang, D; Peskind, ER; Edland, SD; Nochlin, D; DiGiacomo, L; Bowen, JD; McCormick, WC; Teri, L; Raskind, MA; Kukull, WA; Larson, EB (2002). "Clinical and neuropathological characteristics of hippocampal sclerosis: a community-based study". Arch. Neurol. 59 (7): 1099–1106. doi:10.1001/archneur.59.7.1099. PMID 12117357.

- Kadom, N; Tsuchida, T; Gaillard, WD (2011). "Hippocampal sclerosis in children younger than 2 years". Pediatr Radiol. 41 (10): 1239–1245. doi:10.1007/s00247-011-2166-4. PMID 21735179.

- Norwood, BA; Burmanglag, AV; Osculati, F; Sbarbati, A; Marzola, P; Nicolato, E; Fabene, PF; Sloviter, RS (2010). "Classic hippocampal sclerosis and hippocampal-onset epilepsy produced by a single "cryptic" episode of focal hippocampal excitation in awake rats". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 518 (16): 3381–3407. doi:10.1002/cne.22406. PMC 2894278. PMID 20575073.

- Koseoglu, E; Kucuk, S; Arman, F; Erosoy, AO (2009). "Factors that affect interictal cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in temporal lobe epilepsy: Role of hippocampal sclerosis". Epilepsy Behav. 16 (4): 617–621. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.09.021. PMID 19854109.

- Zarow, C; Weiner, MW; Ellis, WG; Chui, HC (2012). "Prevalence, laterality, and comorbidity of hippocampal sclerosis in an autopsy sample". Brain Behav. 2 (4): 435–442. doi:10.1002/brb3.66. PMC 3432966. PMID 22950047.

- Blümcke, I; Thom, M; Wiestler, OD (2002). "Ammon's Horn Sclerosis: A Maldevelopmental Disorder Associated with Temporal Lobe Epilepsy". Brain Pathology. 12: 199–211.

- De Lanerolle, NC; Lee, TS (2005). "New facets of the neuropathology and molecular profile of human temporal lobe epilepsy". Epilepsy Behav. 7 (2): 190–203. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.06.003. PMID 16098816.

- Borelli, P; Shorvon, SD; Stevens, JM; Smith, SJ; Scott, CA; Walker, MC (2008). "Extratemporal ictal clinical features in hippocampal sclerosis: their relationship to the degree of hippocampal volume loss and to the outcome of temporal lobectomy". Epilepsia. 49 (8): 1333–1339. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01694.x. PMID 18557777.

- Blumcke, I; Coras, R; Miyata, H; Ozkara, C (2012). "Defining Clinico-Neuropathological Subtypes of Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy with hippocampal Sclerosis". Brain Pathology. 22 (3): 402–411. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2012.00583.x. PMID 22497612.

- Asuman, OV; Serap, S; Hamit, A; Abdurrahman, C (2009). "Prognosis of patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy due to hippocampal sclerosis". Epilepsy Research. 85 (2): 206–211. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.03.001. PMID 19345070.

- Kim, CH; Koo, BB; Chung, CK; Lee, JM; Kim, JS; Lee, SK (2010). "Thalamic changes in temporal lobe epilepsy with and without hippocampal sclerosis: A diffusion tensor imaging study". Epilepsy Res. 90 (1): 21–27. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.03.002. PMID 20307957.

- Nelson, PT; Schmitt, FA; Lin, YS; Abner, EL; Jicha, GA; Patel, E; Thomason, PC; Neltner, JH; Smith, CD; Santacruz, KS; Sonnen, JA; Poon, LW; Gearing, M; Green, RC; Woodard, JL; Van Eldik, LJ; Rj, Kryscio (2011). "Hippocampal sclerosis in advanced age: clinical and pathological features". Brain. 134 (5): 1506–1518. doi:10.1093/brain/awr053. PMC 3097889. PMID 21596774.

- Hesdorffer, DC; Tian, H; Anand, K; et al. (2005). "Socioeconomic status is a risk factor for epilepsy in Icelandic adults but not in children". Epilepsia. 46 (8): 1297–303. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.10705.x. PMID 16060943.

- Bazendale S, Heaney D (2010). "Socioeconomic status, cognition, and hippocampal sclerosis". Epilepsy Behav. 20 (1): 64–67. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.10.019. PMID 21130698.

- Bronen RA, Fulbright RK, Spencer DD, et al. 1997

- Trepeta, Scott 2007

- Aoki N, Murray ME, Ogaki K, Fujioka S, Rutherford NJ, Rademakers R, Ross OA, Dickson DW (Jan 2015). "Hippocampal sclerosis in Lewy body disease is a TDP-43 proteinopathy similar to FTLD-TDP Type A". Acta Neuropathol. 129 (1): 53–64. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1358-z. PMC 4282950. PMID 25367383.

External links

| Classification |

|---|