Caudate nucleus

The caudate nucleus is one of the structures that make up the corpus striatum, which is a component of the basal ganglia.[1] While the caudate nucleus has long been associated with motor processes due to its role in Parkinson's disease,[2][3] it plays important roles in various other nonmotor functions as well, including procedural learning,[4] associative learning[5] and inhibitory control of action,[6] among other functions. The caudate is also one of the brain structures which compose the reward system and functions as part of the cortico–basal ganglia–thalamic loop.[1]

| Caudate nucleus | |

|---|---|

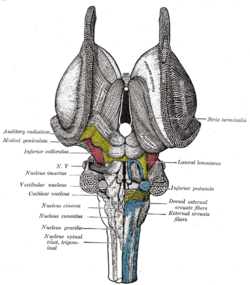

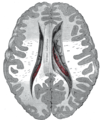

Transverse Cut of Brain (Horizontal Section), basal ganglia is blue | |

| Details | |

| Part of | dorsal striatum |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nucleus caudatus |

| MeSH | D002421 |

| NeuroNames | 226 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1373 |

| TA | A14.1.09.502 |

| FMA | 61833 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Structure

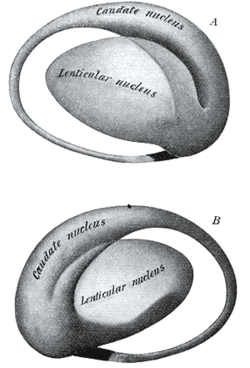

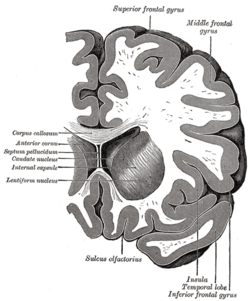

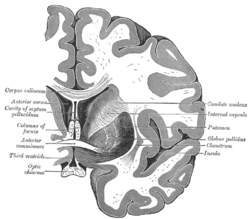

Together with the putamen, the caudate forms the dorsal striatum, which is considered a single functional structure; anatomically, it is separated by a large white matter tract, the internal capsule, so it is sometimes also referred to as two structures: the medial dorsal striatum (the caudate) and the lateral dorsal striatum (the putamen). In this vein, the two are functionally distinct not as a result of structural differences, but merely due to the topographical distribution of function.

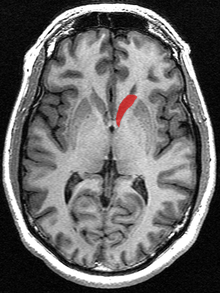

The caudate nuclei are located near the center of the brain, sitting astride the thalamus. There is a caudate nucleus within each hemisphere of the brain. Individually, they resemble a C-shape structure with a wider "head" (caput in Latin) at the front, tapering to a "body" (corpus) and a "tail" (cauda). Sometimes a part of the caudate nucleus is referred to as the "knee" (genu).[7] The caudate head receives its blood supply from the lenticulostriate artery while the tail of the caudate receives its blood supply from the anterior choroidal artery.[8]

The head and body of the caudate nucleus form part of the floor of the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle. After the body travels briefly towards the back of the head, the tail curves back toward the anterior, forming the roof of the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle. This means that a coronal (on a plane parallel to the face) section that cuts through the tail will also cross the body and head of the caudate nucleus.

Neurochemistry

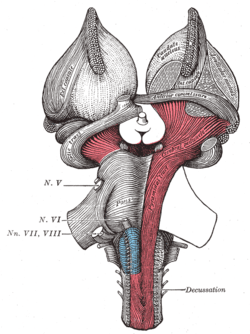

The caudate is highly innervated by dopamine neurons that originate from the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc). The SNc is located in the midbrain and contains cell projections to the caudate and putamen, utilizing the neurotransmitter dopamine.[9] There are also additional inputs from various association cortices.

Motor functions

Spatial mnemonic processing

The caudate nucleus integrates spatial information with motor behavior formulation. Selective impairment of spatial working memory in subjects with Parkinson's disease and the knowledge of the disease's impact on the amount of dopamine supplied to the striatum have linked the caudate nucleus to spatial and nonspatial mnemonic processing. Spatially dependent motor preparation has been linked to the caudate nucleus through event-related fMRI analysis techniques. Activity in the caudate nucleus was demonstrated to be greater during tasks featuring spatial and motoric memory demands than those that involved nonspatial tasks.[10] Specifically, spatial working memory activity has been observed, via fMRI studies of delayed recognition, to be greater in the caudate nucleus when the activity immediately preceded a motor response. These results indicate that the caudate nucleus could be involved in coding a motor response. With this in mind, the caudate nucleus could be involved in the recruitment of the motor system to support working memory performance by the mediation of sensory-motor transformations.[11]

Directed movements

The caudate nucleus contributes importantly to body and limbs posture and the speed and accuracy of directed movements. Deficits in posture and accuracy during paw usage tasks were observed following the removal of caudate nuclei in felines. A delay in initiating performance and the need to constantly shift body position were both observed in cats following partial removal of the nuclei.[12]

Following the application of cocaine to the caudate nucleus and the resulting lesions produced, a "leaping or forward movement" was observed in monkeys. Due to its association with damage to the caudate, this movement demonstrates the inhibitory nature of the caudate nucleus. The "motor release" observed as a result of this procedure indicates that the caudate nucleus inhibits the tendency for an animal to move forward without resistance.[13]

Cognitive functions

Goal-directed action

A review of neuroimaging studies, anatomical studies of caudate connectivity, and behavioral studies reveals a surprising role for the caudate in executive functioning. A study of Parkinson's patients (see below) may also contribute to a growing body of evidence.

A two-pronged approach of neuroimaging (including PET and fMRI) and anatomical studies expose a strong relationship between the caudate and cortical areas associated with executive functioning: "non-invasive measures of anatomical and functional connectivity in humans demonstrate a clear link between the caudate and executive frontal areas."[14]

Meanwhile, behavioral studies provide another layer to the argument: recent studies suggest that the caudate is fundamental to goal-directed action, that is, "the selection of behavior based on the changing values of goals and a knowledge of which actions lead to what outcomes."[14] One such study presented rats with levers that triggered the release of a cinnamon flavored solution. After the rats learned to press the lever, the researchers changed the value of the outcome (the rats were taught to dislike the flavor either by being given too much of the flavor, or by making the rats ill after drinking the solution) and the effects were observed. Normal rats pressed the lever less frequently, while rats with lesions in the caudate did not suppress the behavior as effectively. In this way, the study demonstrates the link between the caudate and goal-directed behavior; rats with damaged caudate nuclei had difficulty assessing the changing value of the outcome.[14] In a 2003-human behavioral study, a similar process was repeated, but the decision this time was whether or not to trust another person when money was at stake.[15] While here the choice was far more complex––the subjects were not simply asked to press a lever, but had to weigh a host of different factors––at the crux of the study was still behavioral selection based on changing values of outcomes.

In short, neuroimagery and anatomical studies support the assertion that the caudate plays a role in executive functioning, while behavioral studies deepen our understanding of the ways in which the caudate guides some of our decision-making processes.

Memory

The dorsal-prefrontal cortex subcortical loop involving the caudate nucleus has been linked to deficits in working memory, specifically in schizophrenic patients. Functional imaging has shown activation of this subcortical loop during working memory tasks in primates and healthy human subjects. The caudate may be affiliated with deficits involving working memory from before illness onset as well. Caudate nucleus volume has been found to be inversely associated with perseverative errors on spatial working memory tasks.[16][17]

The amygdala sends direct projections to the caudate nucleus. Both the amygdala and the caudate nucleus have direct and indirect projections to the hippocampus. The influence of the amygdala on memory processing in the caudate nucleus has been demonstrated with the finding that lesions involving the connections between these two structures "block the memory-enhancing effects of oxotremorine infused into the caudate nucleus". In a study involving rats given water-maze training, the caudate nucleus was discovered to enhance memory of visually cued training after amphetamine was infused post-training into the caudate.[18]

Learning

In a 2005 study, subjects were asked to learn to categorize visual stimuli by classifying images and receiving feedback on their responses. Activity associated with successful classification learning (correct categorization) was concentrated to the body and tail of the caudate, while activity associated with feedback processing (the result of incorrect categorization) was concentrated to the head of the caudate.[19]

Sleep

Bilateral lesions in the head of the caudate nucleus in cats were correlated with a decrease in the duration of deep slow wave sleep during the sleep-wakefulness cycle. With a decrease in total volume of deep slow wave sleep, the transition of short-term memory to long-term memory may also be affected negatively.[20] However, the effects of caudate nuclei removal on the sleep-wakefulness pattern of cats have not been permanent. Normalization has been discovered after a period of three months following caudate nuclei ablation. This discovery could be due to the inter-related nature of the roles of the caudate nucleus and the frontal cortex in controlling levels of central nervous system activation. The cats with caudate removal, although permanently hyperactive, had a significant decrease in rapid eye movement sleep (REMS) time that only lasted for about two months. However, afrontal cats had a permanent decrease in REMS time and only a temporary period of hyperactivity.[21]

Contrasting with associations between "deep", REM sleep and the caudate nucleus, a study involving EEG and fMRI measures during human sleep cycles has indicated that the caudate nucleus demonstrates reduced activity during non-REM sleep across all sleep stages.[22] Additionally, studies of human caudate nuclei volume in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS) subjects established a correlation between CCHS and a significant reduction in left and right caudate volume. CCHS is a genetic disorder that affects the sleep cycle due to a reduced drive to breathe. Therefore, the caudate nucleus has been suggested to play a role in human sleep cycles.[23]

Emotion

The caudate nucleus has been implicated in responses to visual beauty, and has been suggested as one of the "neural correlates of romantic love".[24][25]

Approach-attachment behavior and affect are also controlled by the caudate nucleus. Cats with bilateral removal of the caudate nuclei persistently approached and followed objects, attempting to contact the target, while exhibiting a friendly disposition by the elicitation of treading of the forelimbs and purring. The magnitude of the behavioral responses was correlated to the extent of the removal of the nuclei. Reports of human patients with selective damage to the caudate nucleus show unilateral caudate damage resulting in loss of drive, obsessive-compulsive disorder, stimulus-bound perseverative behavior, and hyperactivity. Most of these deficits can be classified as relating to approach-attachment behaviors, from approaching a target to romantic love.[12]

Language

Neuroimaging studies reveal that people who can communicate in multiple languages activate exactly the same brain regions regardless of the language. A 2006 publication studies this phenomenon and identifies the caudate as a center for language control. In perhaps the most illustrative case, a trilingual subject with a lesion to the caudate was observed. The patient maintained language comprehension in her three languages, but when asked to produce language, she involuntarily switched between the three languages. In short, "these and other findings with bilingual patients suggest that the left caudate is required to monitor and control lexical and language alternatives in production tasks."[26][27]

Local shape deformations of the medial surface of the caudate have been correlated with verbal learning capacity for females and the number of perseverance errors on spatial and verbal fluency working memory tasks for males. Specifically, a larger caudate nucleus volume has been linked with better verbal fluency performance.[16]

A neurological study of glossolalia showed a significant reduction in activity in the left caudate nucleus during glossolalia compared to singing in English.[28]

Threshold control

The brain contains large collections of neurons reciprocally connected by excitatory synapses, thus forming large network of elements with positive feedback. It is difficult to see how such a system can operate without some mechanism to prevent explosive activation. There is some indirect evidence[29] that the caudate may perform this regulatory role by measuring the general activity of cerebral cortex and controlling the threshold potential.

Clinical significance

Alzheimer's disease

A 2013 study has suggested a link between Alzheimer's patients and the caudate nucleus. MRI images were used to estimate the volume of caudate nuclei in patients with Alzheimer's and normal volunteers. The study found a "significant reduction in the caudate volume" in Alzheimer's patients when compared to the normal volunteers. While the correlation does not indicate causation, the finding may have implications for early diagnosis.[30]

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease is likely the most studied basal ganglia disorder. Patients with this progressive neurodegenerative disorder often first experience movement related symptoms (the three most common being tremors at rest, muscular rigidity, and akathisia) which are later combined with various cognitive deficiencies, including dementia.[31] Parkinson's disease depletes dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal tract, a dopamine pathway that is connected to the head of the caudate. As such, many studies have correlated the loss of dopaminergic neurons that send axons to the caudate nucleus and the degree of dementia in Parkinson's patients.[14] And while a relationship has been drawn between the caudate and Parkinson's motor deficiencies, the caudate has also been associated with Parkinson's concomitant cognitive impairments. One review contrasts the performance of patients with Parkinson's and patients that strictly suffered from frontal-lobe damage in the Tower of London test. The differences in performance between the two types of patients (in a test that, in short, requires subjects to select appropriate intermediate goals with a larger goal in mind) draws a link between the caudate and goal-directed action. However, the studies are not conclusive. While the caudate has been associated with executive function (see "Goal-Directed Action"), it remains "entirely unclear whether executive deficits in [Parkinson's patients] reflect pre-dominantly their cortical or subcortical damage."[14]

Huntington's disease

In Huntington's disease, a genetic mutation occurs in the HTT gene which encodes for Htt protein. The Htt protein interacts with over 100 other proteins, and appears to have multiple biological functions.[32] The behavior of this mutated protein is not completely understood, but it is toxic to certain cell types, particularly in the brain. Early damage is most evident in the striatum, but as the disease progresses, other areas of the brain are also more conspicuously affected. Early symptoms are attributable to functions of the striatum and its cortical connections—namely control over movement, mood and higher cognitive function.[33]

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

A 2002 study draws a relationship between caudate asymmetry and symptoms related to ADHD. The authors used MR images to compare the relative volumes of the caudate nuclei (as the caudate is a bilateral structure), and drew a connection between any asymmetries and symptoms of ADHD: "The degree of caudate asymmetry significantly predicted cumulative severity ratings of inattentive behaviors." This correlation is congruent with previous associations of the caudate with attentional functioning.[34] A more recent 2018 study replicated these findings, and demonstrated that the caudate asymmetries related to ADHD were more pronounced in the dorsal medial regions of the caudate.[35]

Schizophrenia

The volume of white matter in the caudate nucleus has been linked with patients diagnosed with Schizophrenia. A 2004 study uses magnetic resonance imaging to compare the relative volume of white matter in the caudate among Schizophrenia patients. Those patients who suffer from the disorder have "smaller absolute and relative volumes of white matter in the caudate nucleus than healthy subjects."[36]

Bipolar type I

A 2014 study found Type I Bipolar patients had relatively higher volume of gray and white matter in the caudate nucleus and other areas associated with reward processing and decision making, compared to controls and Bipolar II subjects. Overall the amount of gray and white matter in Bipolar patients was lower than controls.[37][38]

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

It has been theorized that the caudate nucleus may be dysfunctional in persons with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), in that it may perhaps be unable to properly regulate the transmission of information regarding worrying events or ideas between the thalamus and the orbitofrontal cortex.

A neuroimaging study with positron emission tomography found that the right caudate nucleus had the largest change in glucose metabolism after patients had been treated with paroxetine.[39] Recent SDM meta-analyses of voxel-based morphometry studies comparing people with OCD and healthy controls have found people with OCD to have increased grey matter volumes in bilateral lenticular nuclei, extending to the caudate nuclei, while decreased grey matter volumes in bilateral dorsal medial frontal/anterior cingulate gyri.[40][41] These findings contrast with those in people with other anxiety disorders, who evince decreased (rather than increased) grey matter volumes in bilateral lenticular / caudate nuclei, while also decreased grey matter volumes in bilateral dorsal medial frontal/anterior cingulate gyri.[41]

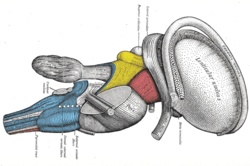

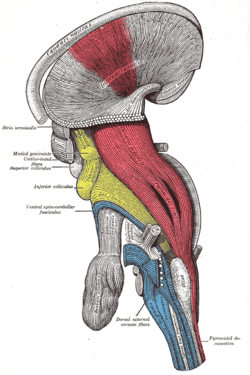

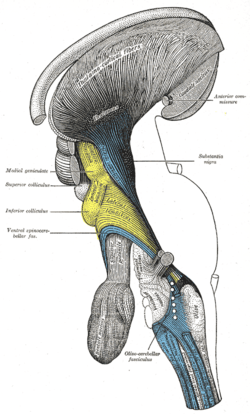

Additional images

References

- Yager LM, Garcia AF, Wunsch AM, Ferguson SM (August 2015). "The ins and outs of the striatum: Role in drug addiction". Neuroscience. 301: 529–541. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.033. PMC 4523218. PMID 26116518.

- Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 147–148. ISBN 9780071481274.

- Bear, , Mark F. (2016). Neuroscience : exploring the brain. Connors, Barry W.,, Paradiso, Michael A. (Fourth ed.). Philadelphia. p. 502. ISBN 9780781778176. OCLC 897825779.

- Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 326. ISBN 9780071481274.

Evidence that the caudate nucleus and putamen influence stimulus-response learning comes from lesion studies in rodents and primates and from neuroimaging studies in humans and from studies of human disease. In Parkinson disease, the dopaminergic innervation of the caudate and putamen is severely compromised by the death of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (Chapter 17). Patients with Parkinson disease have normal declarative memory (unless they have a co-occurring dementia as may occur in Lewy body disease.) However, they have marked impairments of stimulus-response learning. Patients with Parkinson disease or other basal ganglia disorders such as Huntington disease (in which caudate neurons themselves are damaged) have deficits in other procedural learning tasks, such as the acquisition of new motor programs.

- Anderson BA, Kuwabara H, Wong DF, Roberts J, Rahmim A, Brašić JR, Courtney SM (August 2017). "Linking dopaminergic reward signals to the development of attentional bias: A positron emission tomographic study". NeuroImage. 157: 27–33. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.05.062. PMC 5600829. PMID 28572059.

- Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 321. ISBN 9780071481274.

Functional neuroimaging in humans demonstrates activation of the prefrontal cortex and caudate nucleus (part of the striatum) in tasks that demand inhibitory control of behavior.

- Yeterian EH, Pandya DN (February 1995). "Corticostriatal connections of extrastriate visual areas in rhesus monkeys". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 352 (3): 436–57. doi:10.1002/cne.903520309. PMID 7706560.

- D'Souza, Donna. "Cerebral vascular territories - Radiology Reference Article - Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org.

- McDougal, David. "Substantia Nigra". Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- Postle BR, D'Esposito M (July 1999). "Dissociation of human caudate nucleus activity in spatial and nonspatial working memory: an event-related fMRI study". Brain Research. Cognitive Brain Research. 8 (2): 107–15. doi:10.1016/s0926-6410(99)00010-5. PMID 10407200.

- Postle BR, D'Esposito M (June 2003). "Spatial working memory activity of the caudate nucleus is sensitive to frame of reference". Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 3 (2): 133–44. doi:10.3758/cabn.3.2.133. PMID 12943328.

- Villablanca JR (2010). "Why do we have a caudate nucleus?". Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis. 70 (1): 95–105. PMID 20407491.

- White NM (April 2009). "Some highlights of research on the effects of caudate nucleus lesions over the past 200 years". Behavioural Brain Research. 199 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.003. PMID 19111791.

- Grahn JA, Parkinson JA, Owen AM (April 2009). "The role of the basal ganglia in learning and memory: neuropsychological studies". Behavioural Brain Research. 199 (1): 53–60. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.020. PMID 19059285.

- Elliott R, Newman JL, Longe OA, Deakin JF (January 2003). "Differential response patterns in the striatum and orbitofrontal cortex to financial reward in humans: a parametric functional magnetic resonance imaging study". The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (1): 303–7. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00303.2003. PMC 6742125. PMID 12514228.

- Hannan KL, Wood SJ, Yung AR, Velakoulis D, Phillips LJ, Soulsby B, Berger G, McGorry PD, Pantelis C (June 2010). "Caudate nucleus volume in individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis: a cross-sectional magnetic resonance imaging study". Psychiatry Research. 182 (3): 223–30. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.02.006. PMID 20488675.

- Levitt JJ, McCarley RW, Dickey CC, Voglmaier MM, Niznikiewicz MA, Seidman LJ, Hirayasu Y, Ciszewski AA, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Shenton ME (July 2002). "MRI study of caudate nucleus volume and its cognitive correlates in neuroleptic-naive patients with schizotypal personality disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (7): 1190–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1190. PMC 2826363. PMID 12091198.

- McGaugh JL (2004). "The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 27: 1–28. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144157. PMID 15217324.

- Seger CA, Cincotta CM (March 2005). "The roles of the caudate nucleus in human classification learning". The Journal of Neuroscience. 11. 25 (11): 2941–51. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3401-04.2005. PMC 6725143. PMID 15772354.

- Gogichadze M, Oniani MT, Nemsadze M, Oniani N (2009). "Sleep disorders and disturbances in memory processing related to the lesion of the caudate nucleus". Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 15: S167–S168. doi:10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70639-X.

- Villablanca JR (September 2004). "Counterpointing the functional role of the forebrain and of the brainstem in the control of the sleep-waking system". Journal of Sleep Research. 13 (3): 179–208. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00412.x. PMID 15339255.

- Kaufmann C, Wehrle R, Wetter TC, Holsboer F, Auer DP, Pollmächer T, Czisch M (March 2006). "Brain activation and hypothalamic functional connectivity during human non-rapid eye movement sleep: an EEG/fMRI study". Brain. 129 (Pt 3): 655–67. doi:10.1093/brain/awh686. PMID 16339798.

- Kumar R, Ahdout R, Macey PM, Woo MA, Avedissian C, Thompson PM, Harper RM (November 2009). "Reduced caudate nuclei volumes in patients with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome". Neuroscience. 163 (4): 1373–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.038. PMC 2761724. PMID 19632307.

- Ishizu T, Zeki S (May 2011). Warrant EJ (ed.). "Toward a brain-based theory of beauty". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e21852. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021852. PMC 3130765. PMID 21755004.

- Aron A, Fisher H, Mashek DJ, Strong G, Li H, Brown LL (July 2005). "Reward, motivation, and emotion systems associated with early-stage intense romantic love". Journal of Neurophysiology. 94 (1): 327–37. doi:10.1152/jn.00838.2004. PMID 15928068.

- Crinion J, Turner R, Grogan A, Hanakawa T, Noppeney U, Devlin JT, Aso T, Urayama S, Fukuyama H, Stockton K, Usui K, Green DW, Price CJ (June 2006). "Language control in the bilingual brain". Science. 312 (5779): 1537–40. doi:10.1126/science.1127761. PMID 16763154.

- "How bilingual brains switch between tongues". newscientist.com.

- Newberg AB, Wintering NA, Morgan D, Waldman MR (November 2006). "The measurement of regional cerebral blood flow during glossolalia: a preliminary SPECT study". Psychiatry Research. 148 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.07.001. PMID 17046214.

- Braitenberg V. (1984) Vehicles. Experiments in synthetic psychology.

- Jiji S, Smitha KA, Gupta AK, Pillai VP, Jayasree RS (September 2013). "Segmentation and volumetric analysis of the caudate nucleus in Alzheimer's disease". European Journal of Radiology. 82 (9): 1525–30. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.03.012. PMID 23664648.

- Kolb, Bryan; Ian Q. Whishaw (2001). An Introduction to Brain and Behavior (4th ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. p. 590. ISBN 978-1429242288.

- Goehler H, Lalowski M, Stelzl U, Waelter S, Stroedicke M, Worm U, Droege A, Lindenberg KS, Knoblich M, Haenig C, Herbst M, Suopanki J, Scherzinger E, Abraham C, Bauer B, Hasenbank R, Fritzsche A, Ludewig AH, Büssow K, Buessow K, Coleman SH, Gutekunst CA, Landwehrmeyer BG, Lehrach H, Wanker EE (September 2004). "A protein interaction network links GIT1, an enhancer of huntingtin aggregation, to Huntington's disease". Molecular Cell. 15 (6): 853–65. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.016. PMID 15383276.

- Walker FO (January 2007). "Huntington's disease". Lancet. 369 (9557): 218–28. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. PMID 17240289.

- Schrimsher GW, Billingsley RL, Jackson EF, Moore BD (December 2002). "Caudate nucleus volume asymmetry predicts attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptomatology in children". Journal of Child Neurology. 17 (12): 877–84. doi:10.1177/08830738020170122001. PMID 12593459.

- Douglas PK, Gutman B, Anderson A, Larios C, Lawrence KE, Narr K, Sengupta B, Cooray G, Douglas DB, Thompson PM, McGough JJ, Bookheimer SY (February 2018). "Hemispheric brain asymmetry differences in youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". NeuroImage: Clinical. 18: 744–52. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2018.02.020. PMC 5988460. PMID 29876263.

- Takase K, Tamagaki C, Okugawa G, Nobuhara K, Minami T, Sugimoto T, Sawada S, Kinoshita T (2004). "Reduced white matter volume of the caudate nucleus in patients with schizophrenia". Neuropsychobiology. 50 (4): 296–300. doi:10.1159/000080956. PMID 15539860. ProQuest 293981781.

- Maller, Jerome J.; Thaveenthiran, Prasanthan; Thomson, Richard H.; McQueen, Susan; Fitzgerald, Paul B. (2014). "Volumetric, cortical thickness and white matter integrity alterations in bipolar disorder type I and II". Journal of Affective Disorders. 169: 118–127. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.016. PMID 25189991.

- "A Trip Into Bipolar Brains". psmag.com.

- Hansen ES, Hasselbalch S, Law I, Bolwig TG (March 2002). "The caudate nucleus in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Reduced metabolism following treatment with paroxetine: a PET study". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 5 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1017/S1461145701002681. PMID 12057027.

- Radua J, Mataix-Cols D (November 2009). "Voxel-wise meta-analysis of grey matter changes in obsessive-compulsive disorder". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 195 (5): 393–402. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055046. PMID 19880927.

- Radua J, van den Heuvel OA, Surguladze S, Mataix-Cols D (July 2010). "Meta-analytical comparison of voxel-based morphometry studies in obsessive-compulsive disorder vs other anxiety disorders". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (7): 701–11. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.70. PMID 20603451.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caudate nucleus. |

- Stained brain slice images which include the "caudate nucleus" at the BrainMaps project

- Diagram at uni-tuebingen.de

- NIF Search - Caudate Nucleus via the Neuroscience Information Framework