Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcosis, is a potentially fatal fungal disease. It is caused by one of two species; Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. Both were previously thought to be subspecies of C. neoformans but have now been identified as distinct species.

| Cryptococcosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cryptococcal disease |

| |

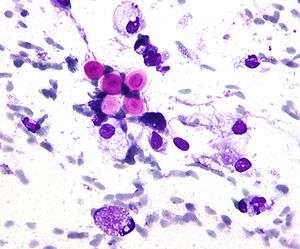

| Micrograph of cryptococcosis showing the characteristically thick capsule of cryptococcus. Field stain. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, Pulmonology |

Cryptococcosis is believed to be acquired by inhalation of the infectious propagule from the environment. Although the exact nature of the infectious propagule is unknown, the leading hypothesis is the basidiospore created through sexual or asexual reproduction.

Cause

Cryptococcosis is a defining opportunistic infection for AIDS, and is the second-most-common AIDS-defining illness in Africa. Other conditions that pose an increased risk include certain lymphomas (e.g., Hodgkin's lymphoma), sarcoidosis, liver cirrhosis, and patients on long-term corticosteroid therapy.

Distribution is worldwide in soil.[3] The prevalence of cryptococcosis has been increasing over the past 20 years for many reasons, including the increase in incidence of AIDS and the expanded use of immunosuppressive drugs.

In humans, C. neoformans causes three types of infections:

- Wound or cutaneous cryptococcosis

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis

- Cryptococcal meningitis.

Cryptococcal meningitis (infection of the meninges, the tissue covering the brain) is believed to result from dissemination of the fungus from either an observed or unappreciated pulmonary infection. Often there is also silent dissemination throughout the brain when meningitis is present. Cryptococcus gattii causes infections in immunocompetent people (fully functioning immune system), but C. neoformans v. grubii, and v. neoformans usually only cause clinically evident infections in persons with some form of defect in their immune systems (immunocompromised persons). People with defects in their cell-mediated immunity, for example, people with AIDS, are especially susceptible to disseminated cryptococcosis. Cryptococcosis is often fatal, even if treated. It is estimated that the three-month case-fatality rate is 9% in high-income regions, 55% in low/middle-income regions, and 70% in sub-Saharan Africa. As of 2009 there were globally approximately 958,000 annual cases and 625,000 deaths within three months after infection.[4]

Although the most common presentation of cryptococcosis is of C. neoformans infection in an immunocompromised person (such as persons living with AIDS), the C. gattii is being increasingly recognised as a pathogen in what is presumed to be immunocompetent hosts,[5] especially in Canada and Australia. This may be due to rare exposure and high pathogenicity, or to unrecognised isolated defects in immunity, specific for this organism.

Diagnosis

Dependent on the infectious syndrome, symptoms include fever, fatigue, dry cough, headache, blurred vision, and confusion.[6] Symptom onset is often subacute, progressively worsened over several weeks. The two most common presentations are meningitis (an infection in and around the brain) and pulmonary (lung) infection.

Any person who is found to have cryptococcosis at a site outside of the central nervous system (e.g., pulmonary cryptococcosis), a lumbar puncture is indicated to evaluate the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for evidence of cryptococcal meningitis, even if they do not have signs or symptoms of CNS disease. Detection of cryptococcal antigen (capsular material) by culture of CSF, sputum and urine provides definitive diagnosis.[7] Blood cultures may be positive in heavy infections. India ink of the CSF is a traditional microscopic method of diagnosis,[8] although the sensitivity is poor in early infection, and may miss 15–20% of patients with culture-positive cryptococcal meningitis.[9] Unusual morphological forms are rarely seen.[10] Cryptococcal antigen from cerebrospinal fluid is the best test for diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis in terms of sensitivity.[11] Apart from conventional methods of detection like direct microscopy and culture, rapid diagnostic methods to detect cryptococcal antigen by latex agglutination test, lateral flow immunochromatographic assay (LFA), or enzyme immunoassay (EIA). A new cryptococcal antigen LFA was FDA approved in July 2011.[9][12] Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been used on tissue specimens.

Cryptococcosis can rarely occur in the non-immunosuppressed people, particularly with Cryptococcus gattii.

Prevention

Cryptococcosis is a very subacute infection with a prolonged subclinical phase lasting weeks to months in persons with HIV/AIDS before the onset of symptomatic meningitis. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence rates of detectable cryptococcal antigen in peripheral blood is often 4–12% in persons with CD4 counts lower than 100 cells/mcL.[13][14] Cryptococcal antigen screen and preemptive treatment with fluconazole is cost saving to the healthcare system by avoiding cryptococcal meningitis.[15] The World Health Organization recommends cryptococcal antigen screening in HIV-infected persons entering care with CD4<100 cells/μL.[16] This undetected subclinical cryptococcal (if not preemptively treated with anti-fungal therapy) will often go on to develop cryptococcal meningitis, despite receiving HIV therapy.[14][17] Cryptococcosis accounts for 20-25% of the mortality after initiating HIV therapy in Africa. What is effective preemptive treatment is unknown, with the current recommendations on dose and duration based on expert opinion. Screening in the United States is controversial, with official guidelines not recommending screening, despite cost-effectiveness and a 3% U.S. cryptococcal antigen prevalence in CD4<100 cells/μL.[18][19]

Treatment

Treatment options in persons without HIV-infection have not been well studied. Intravenous Amphotericin B combined with flucytosine by mouth is recommended for initial treatment (induction therapy).[20]

Persons living with AIDS often have a greater burden of disease and higher mortality (30–70% at 10-weeks), but recommended therapy is with amphotericin B and flucytosine. Where flucytosine is not available (many low and middle income countries), fluconazole should be used with amphotericin.[16] Amphotericin-based induction therapy has much greater microbiologic activity than fluconazole monotherapy with 30% better survival at 10-weeks.[7][21] Based on a systematic review of existing data, the most cost-effective induction treatment in resource-limited settings appears to be one week of amphotericin B coupled with high-dose fluconazole.[21] After initial induction treatment as above, typical consolidation therapy is with oral fluconazole for at least 8 weeks used with secondary prophylaxis with fluconazole thereafter.[16]

The decision on when to start treatment for HIV appears to be very different than other opportunistic infections. A large multi-site trial supports deferring ART for 4–6 weeks was overall preferable with 15% better 1-year survival than earlier ART initiation at 1–2 weeks after diagnosis.[22] A Cochrane review also supports the delayed starting of treatment until cryptococcosis starts improving with antifungal treatment.[23]

IRIS in those with normal immune function

The immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) has been described in those with normal immune function with meningitis caused by C. gattii and C. grubii. Several weeks or even months into appropriate treatment, there can be deterioration with worsening meningitis symptoms and progression or development of new neurological symptoms. IRIS is however much more common in those with poor immune function (≈25% vs. ≈8%).

Magnetic resonance imaging shows increase in the size of brain lesions, and CSF abnormalities (white cell count, protein, glucose) increase. Radiographic appearance of cryptococcal IRIS brain lesions can mimic that of toxoplasmosis with ring enhancing lesions on head computed tomography (CT). CSF culture is sterile, and there is no increase in CSF cryptococcal antigen titre.

The increasing inflammation can cause brain injury or be fatal.[24][25][26]

The mechanism behind IRIS in cryptococcal meningitis is primarily immunologic. With reversal of immunosuppression, there is paradoxical increased inflammation as the recovering immune system recognises the fungus. In severe IRIS cases, treatment with systemic corticosteroids has been utilized – although evidence-based data are lacking.

Other animals

Cryptococcosis is also seen in cats and occasionally dogs. It is the most common deep fungal disease in cats, usually leading to chronic infection of the nose and sinuses, and skin ulcers. Cats may develop a bump over the bridge of the nose from local tissue inflammation. It can be associated with FeLV infection in cats. Cryptococcosis is most common in dogs and cats but cattle, sheep, goats, horses, wild animals, and birds can also be infected. Soil, fowl manure, and pigeon droppings are among the sources of infection.[27][28]

References

- "Cryptococcosis". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Cryptococcosis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Meningitis: cryptococcal: Overview". Medical Reference: Encyclopedia. University of Maryland Medical Center. September 2010.

- Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM (2009-02-20). "Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS". AIDS. 23 (4): 525–30. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. PMID 19182676.

- Tripathi K, Mor V, Bairwa NK, Del Poeta M, Mohanty BK (2012). "Hydroxyurea treatment inhibits proliferation of Cryptococcus neoformans in mice". Front Microbiol. 3: 187. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00187. PMC 3390589. PMID 22783238.

- Barron MA, Madinger NE (November 18, 2008). "Opportunistic Fungal Infections, Part 3: Cryptococcosis, Histoplasmosis, Coccidioidomycosis, and Emerging Mould Infections". Infections in Medicine.

- Rhein, J; Boulware DR (2012). "Prognosis and management of cryptococcal meningitis in patients with HIV infection". Neurobehavioral HIV Medicine. 4: 45. doi:10.2147/NBHIV.S24748.

- Zerpa, R; Huicho, L; Guillén, A (September 1996). "Modified India ink preparation for Cryptococcus neoformans in cerebrospinal fluid specimens" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 34 (9): 2290–1. PMC 229234. PMID 8862601.

- Boulware, DR; Rolfes, MA; Rajasingham, R; von Hohenberg, M; Qin, Z; Taseera, K; Schutz, C; Kwizera, R; Butler, EK; Meintjes, G; Muzoora, C; Bischof, JC; Meya, DB (Jan 2014). "Multisite validation of cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay and quantification by laser thermal contrast". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (1): 45–53. doi:10.3201/eid2001.130906. PMC 3884728. PMID 24378231.

- Shashikala; Kanungo, R; Srinivasan, S; Mathew, R; Kannan, M (Jul–Sep 2004). "Unusual morphological forms of Cryptococcus neoformans in cerebrospinal fluid". Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 22 (3): 188–90. PMID 17642731.

- Antinori, Spinello; Radice, Anna; Galimberti, Laura; Magni, Carlo; Fasan, Marco; Parravicini, Carlo (November 2005). "The role of cryptococcal antigen assay in diagnosis and monitoring of cryptococcal meningitis" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 43 (11): 5828–9. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.11.5828-5829.2005. PMC 1287839. PMID 16272534.

- Jarvis JN, Percival A, Bauman S, Pelfrey J, Meintjes G, Williams GN, et al. (2011). "Evaluation of a novelpoint-of-care cryptococcal antigen test on serum, plasma, and urine frompatients with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis". Clin Infect Dis. 53 (10): 1019–23. doi:10.1093/cid/cir613. PMC 3193830. PMID 21940419.

- "FIGURE 1. Prevalence of asymptomatic antigenemia with corresponding cost per life saved based on LFA cost of $2.50 per test".

- Meya DB, Manabe YC, Castelnuovo B, Cook BA, Elbireer AM, Kambugu A, Kamya MR, Bohjanen PR, Boulware DR (August 2010). "Cost-effectiveness of serum cryptococcal antigen screening to prevent deaths among HIV-infected persons with a CD4+ cell count < or = 100 cells/microL who start HIV therapy in resource-limited settings". Clin. Infect. Dis. 51 (4): 448–55. doi:10.1086/655143. PMC 2946373. PMID 20597693.

- Rajasingham, R; Meya, DB; Boulware, DR (Apr 15, 2012). "Integrating cryptococcal antigen screening and pre-emptive treatment into routine HIV care". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 59 (5): e85–91. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824c837e. PMC 3311156. PMID 22410867.

- World Health Organization. "Rapid advice: Diagnosis, prevention and management of cryptococcal disease in HIV-infected adults, adolescents, and children". Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Jarvis, JN; Harrison, TS; Govender, N; Lawn, SD; Longley, N; Bicanic, T; Maartens, G; Venter, F; Bekker, LG; Wood, R; Meintjes, G (2011). "Routine cryptococcal antigen screening for HIV-infected patients with low CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts—time to implement in South Africa?" (PDF). South African Medical Journal. 101 (4): 232–4. doi:10.7196/samj.4752. PMID 21786721.

- Rajasingham, R; Boulware, DR (Dec 2012). "Reconsidering cryptococcal antigen screening in the U.S. among persons with CD4 <100 cells/mcL". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 55 (12): 1742–4. doi:10.1093/cid/cis725. PMC 3501329. PMID 22918997.

- McKenney J, Smith RM, Chiller TM, Detels R, French A, Margolick J, Klausner JD (July 2014). "Prevalence and correlates of cryptococcal antigen positivity among AIDS patients—United States, 1986–2012". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 63 (27): 585–7. PMC 4584711. PMID 25006824.

- "Practice Guidelines for the Management of Cryptococcal Disease". Infectious Disease Society of America. 2010.

- Rajasingham, Radha; Rolfes, M.A.; Birkenkamp, K.E.; Meya, D.B.; Boulware, D.R. (2012). Farrar, Jeremy (ed.). "Cryptococcal Meningitis Treatment Strategies in Resource-Limited Settings: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis". PLoS Medicine. 9 (9): e1001316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001316. PMC 3463510. PMID 23055838.

- Boulware, DR; Meya, DB; Muzoora, Conrad; Rolfes, MA; Huppler Hullsiek, K; Musubire, Abdu; Taseera, Kabanda; Nabeta, HW; Schutz, C; Williams, DA A.; Rajasingham, R; Rhein, J; Thienemann, F; Lo, MW; Nielsen, K; Bergemann, T L.; Kambugu, A; Manabe, YC; Janoff, EN; Bohjanen, PR; Meintjes, G (26 June 2014). "Timing of Antiretroviral Therapy after Diagnosis of Cryptococcal Meningitis". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (26): 2487–2498. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312884. PMC 4127879. PMID 24963568.

- Njei, B; Kongnyuy, EJ; Kumar, S; Okwen, MP; Sankar, MJ; Mbuagbaw, L (Feb 28, 2013). "Optimal timing for antiretroviral therapy initiation in patients with HIV infection and concurrent cryptococcal meningitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD009012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009012.pub2. PMID 23450595.

- Lane M, McBride J, Archer J (August 2004). "Steroid responsive late deterioration in Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii meningitis". Neurology. 63 (4): 713–4. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000134677.29120.62. PMID 15326249.

- Einsiedel L, Gordon DL, Dyer JR (October 2004). "Paradoxical inflammatory reaction during treatment of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii meningitis in an HIV-seronegative woman". Clin. Infect. Dis. 39 (8): e78–82. doi:10.1086/424746. PMID 15486830.

- Ecevit IZ, Clancy CJ, Schmalfuss IM, Nguyen MH (May 2006). "The poor prognosis of central nervous system cryptococcosis among nonimmunosuppressed patients: a call for better disease recognition and evaluation of adjuncts to antifungal therapy". Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 (10): 1443–7. doi:10.1086/503570. PMID 16619158.

- "Deep Fungal Infections". Archived from the original on 2010-04-13.

- Akira Takeuchi, D. V. M. (July 2014). "Feline Cryptococcosis – WSAVA 2003 Congress – VIN". Vin.com.

Further reading

- Perfect JR, et al. (2010). "Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 50 (3): 291–322. doi:10.1086/649858. PMC 5826644. PMID 20047480.

- Gullo FP, et al. (2013). "Cryptococcosis: epidemiology, fungal resistance, and new alternatives for treatment". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 32 (11): 1377–1391. doi:10.1007/s10096-013-1915-8. PMID 24141976.

- Perfect JR, et al. (2005). "Cryptococcus neoformans: a sugar-coated killer with designer genes". FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 45 (11): 395–404. doi:10.1016/j.femsim.2005.06.005. PMID 16055314. (Review)

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

_histiocytic_penumonia.jpg)

_Alcian_blue-PAS.jpg)