Aspergillosis

Aspergillosis is the name given to a wide variety of diseases caused by fungal infections from species of Aspergillus. Aspergillosis occurs in humans, birds and other animals.

| Aspergillosis | |

|---|---|

_invasive_type.jpg) | |

| Pulmonary invasive aspergillosis in a person with interstitial pneumonia (autopsy material), using Grocott's methenamine silver stain | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Aspergillosis occurs in chronic or acute forms which are clinically very distinct. Most cases of acute aspergillosis occur in people with severely compromised immune systems, e.g. those undergoing bone marrow transplantation.[1] Chronic colonization or infection can cause complications in people with underlying respiratory illnesses, such as asthma,[2] cystic fibrosis,[3] sarcoidosis,[4] tuberculosis, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[5] Most commonly, aspergillosis occurs in the form of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA), aspergilloma, or allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA).[6] Some forms are intertwined; for example ABPA and simple aspergilloma can progress to CPA.

Other, noninvasive manifestations include fungal sinusitis (both allergic in nature and with established fungal balls), otomycosis (ear infection), keratitis (eye infection), and onychomycosis (nail infection). In most instances, these are less severe, and curable with effective antifungal treatment.

The most frequently identified pathogens are Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus, ubiquitous organisms capable of living under extensive environmental stress. Most people are thought to inhale thousands of Aspergillus spores daily but without effect due to an efficient immune response. Taken together, the major chronic, invasive, and allergic forms of aspergillosis account for around 600,000 deaths annually worldwide.[4][7][8][9][10]

Symptoms

A fungus ball in the lungs may cause no symptoms and may be discovered only with a chest X-ray, or it may cause repeated coughing up of blood, chest pain, and occasionally severe, even fatal, bleeding. A rapidly invasive Aspergillus infection in the lungs often causes cough, fever, chest pain, and difficulty breathing.

Poorly controlled aspergillosis can disseminate through the blood stream to cause widespread organ damage. Symptoms include fever, chills, shock, delirium, seizures, and blood clots. The person may develop kidney failure, liver failure (causing jaundice), and breathing difficulties. Death can occur quickly.

Aspergillosis of the ear canal causes itching and occasionally pain. Fluid draining overnight from the ear may leave a stain on the pillow. Aspergillosis of the sinuses causes a feeling of congestion and sometimes pain or discharge. It can extend beyond the sinuses.[11]

In addition to the symptoms, an X-ray or computerised tomography (CT) scan of the infected area provides clues for making the diagnosis. Whenever possible, a doctor sends a sample of infected material to a laboratory to confirm identification of the fungus.

Diagnosis

On chest X-ray and CT, pulmonary aspergillosis classically manifests as a halo sign, and later, an air crescent sign.[12] In hematologic patients with invasive aspergillosis, the galactomannan test can make the diagnosis in a noninvasive way. False-positive Aspergillus galactomannan tests have been found in patients on intravenous treatment with some antibiotics or fluids containing gluconate or citric acid such as some transfusion platelets, parenteral nutrition, or PlasmaLyte.

On microscopy, Aspergillus species are reliably demonstrated by silver stains, e.g., Gridley stain or Gomori methenamine-silver.[13] These give the fungal walls a gray-black colour. The hyphae of Aspergillus species range in diameter from 2.5 to 4.5 µm. They have septate hyphae,[14] but these are not always apparent, and in such cases they may be mistaken for Zygomycota.[13] Aspergillus hyphae tend to have dichotomous branching that is progressive and primarily at acute angles of around 45°.[13]

Angioinvasive pulmonary aspergillosis

Angioinvasive pulmonary aspergillosis_invasive_type.jpg) Angioinvasive pulmonary aspergillosis (closeup)

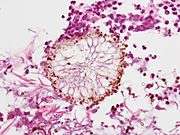

Angioinvasive pulmonary aspergillosis (closeup) Aspergillus vesicle (HE stain)

Aspergillus vesicle (HE stain)

Risk Factors

People who are immunocompromised — such as patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy for leukaemia, or AIDS — are at an increased risk for invasive aspergillosis infections. These people may have neutropenia or corticoid-induced immunosuppression as a result of medical treatments. Neutropenia is often caused by extremely cytotoxic medications such as cyclophosphamide. Cyclophosphamide interferes with cellular replication including that of white blood cells such as neutrophils. A decreased neutrophil count inhibits the ability of the body to mount immune responses against pathogens. Although tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) — a signaling molecule related to acute inflammation responses — is produced, the abnormally low number of neutrophils present in neutropenic patients leads to a depressed inflammatory response. If the underlying neutropenia is not fixed, rapid and uncontrolled hyphal growth of the invasive fungi will occur and result in negative health outcomes.[15]

Prevention

Prevention of aspergillosis involves a reduction of mold exposure via environmental infection-control. Antifungal prophylaxis can be given to high-risk patients. Posaconazole is often given as prophylaxis in severely immunocompromised patients.[16]

Treatment

The current medical treatments for aggressive invasive aspergillosis include voriconazole and liposomal amphotericin B in combination with surgical debridement.[17] For the less aggressive allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, findings suggest the use of oral steroids for a prolonged period of time, preferably for 6–9 months in allergic aspergillosis of the lungs. Itraconazole is given with the steroids, as it is considered to have a "steroid-sparing" effect, causing the steroids to be more effective, allowing a lower dose.[18] Other drugs used, such as amphotericin B, caspofungin (in combination therapy only), flucytosine (in combination therapy only), or itraconazole,[19][20] are used to treat this fungal infection. However, a growing proportion of infections are resistant to the triazoles.[21] A. fumigatus, the most commonly infecting species, is intrinsically resistant to fluconazole.[22]

Epidemiology

Aspergillosis is thought to affect more than 14 million people worldwide,[23] with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA, >4 million), severe asthma with fungal sensitization (>6.5 million), and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA, ∼3 million) being considerably more prevalent than invasive aspergillosis (IA, >300,000). Other common conditions include Aspergillus bronchitis, Aspergillus rhinosinusitis (many millions), otitis externa, and Aspergillus onychomycosis (10 million).[24][25] Alterations in the composition and function of the lung microbiome and mycobiome have been associated with an increasing number of chronic pulmonary diseases such as COPD, cystic fibrosis, chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma.[26]

Animals

While relatively rare in humans, aspergillosis is a common and dangerous infection in birds, particularly in pet parrots. Mallards and other ducks are particularly susceptible, as they often resort to poor food sources during bad weather. Captive raptors, such as falcons and hawks, are susceptible to this disease if they are kept in poor conditions and especially if they are fed pigeons, which are often carriers of "asper". It can be acute in chicks, but chronic in mature birds.

In the United States, aspergillosis has been the culprit in several rapid die-offs among waterfowl. From 8 December until 14 December 2006, over 2,000 mallards died near Burley, Idaho, an agricultural community about 150 miles southeast of Boise. Mouldy waste grain from the farmland and feedlots in the area is the suspected source. A similar aspergillosis outbreak caused by mouldy grain killed 500 mallards in Iowa in 2005.

While no connection has been found between aspergillosis and the H5N1 strain of avian influenza (commonly called "bird flu"), rapid die-offs caused by aspergillosis can spark fears of bird flu outbreaks. Laboratory analysis is the only way to distinguish bird flu from aspergillosis.

In dogs, aspergillosis is an uncommon disease typically affecting only the nasal passages (nasal aspergillosis). This is much more common in dolicocephalic breeds. It can also spread to the rest of the body; this is termed disseminated aspergillosis and is rare, usually affecting individuals with underlying immune disorders.

In 2019, an outbreak of aspergillosis struck the rare kakapo, a large flightless parrot endemic to New Zealand. By June the disease had killed seven of the birds, whose total population at the time was only 142 adults and 72 chicks. One fifth of the population was infected with the disease and the entire species was considered at risk of extinction.[27]

See also

References

- "Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis | Aspergillus & Aspergillosis Website". The Aspergillus Website. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Denning, David W; Pashley, Catherine; Hartl, Domink; Wardlaw, Andrew; Godet, Cendrine; Del Giacco, Stefano; Delhaes, Laurence; Sergejeva, Svetlana (15 April 2014). "Fungal allergy in asthma–state of the art and research needs". Clinical and Translational Allergy. 4 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/2045-7022-4-14. PMC 4005466. PMID 24735832.

- Warris, Adilia; Bercusson, Amelia; Armstrong-James, Darius (April 2019). "Aspergillus colonization and antifungal immunity in cystic fibrosis patients". Medical Mycology. 57 (Supplement_2): S118–S126. doi:10.1093/mmy/myy074. PMID 30816976.

- Denning, D. W.; Pleuvry, A.; Cole, D. C. (March 2013). "Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis complicating sarcoidosis". European Respiratory Journal. 41 (3): 621–6. doi:10.1183/09031936.00226911. PMID 22743676.

- Smith, N; Denning, D.W. (1 April 2011). "Underlying conditions in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis including simple aspergilloma". European Respiratory Journal. 37 (4): 865–872. doi:10.1183/09031936.00054810. PMID 20595150.

- Goel, Ayush. "Pulmonary aspergillosis". Mediconotebook. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Guinea J, Torres-Narbona M, Gijón P, Muñoz P, Pozo F, Peláez T, de Miguel J, Bouza E (June 2010). "Pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: incidence, risk factors, and outcome". Clin Microbiol Infect. 16 (7): 870–7. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03015.x. PMID 19906275.

- Chen, J; Yang Q; Huang J; Li L (September 2013). "Risk factors for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and hospital mortality in acute-on-chronic liver failure patients: A retrospective cohort study". Int J Med Sci. 10 (12): 1625–31. doi:10.7150/ijms.6824. PMC 3804788. PMID 24151434.

- Garcia-Vidal, C; Upton A; Kirby KA; Marr KA (October 2008). "Epidemiology of invasive mold infections in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients: Biological risk factors for infection according to time after transplantation". Clin Infect Dis. 47 (8): 1041–50. doi:10.1086/591969. PMC 2668264. PMID 18781877.

- Nam, HS; Jeon K; Um SW; Suh GY; Chung MP; Kim H; Kwon OJ; Koh WJ (June 2010). "Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis: A review of 43 cases". Int J Infect Dis. 14 (6): 479–482. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.07.011. PMID 19910234.

- Ederies A, Chen J, Aviv RI, et al. (May 2010). "Aspergillosis of the Petrous Apex and Meckel's Cave". Skull Base. 20 (3): 189–92. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1246229. PMC 3037105. PMID 21318037.

- Curtis A, Smith G, Ravin C (1 October 1979). "Air crescent sign of invasive aspergillosis". Radiology. 133 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1148/133.1.17. PMID 472287.

- Kradin RL, Mark EJ (April 2008). "The pathology of pulmonary disorders due to Aspergillus spp". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 132 (4): 606–14. doi:10.1043/1543-2165(2008)132[606:TPOPDD]2.0.CO;2 (inactive 2019-12-14). PMID 18384212.

- "Mycoses: Aspergillosis". Mycology Online. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- Dagenais, Taylor; Keller, Nancy (July 2009). "Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in Invasive Aspergillosis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 22 (3): 447–465. doi:10.1128/CMR.00055-08. PMC 2708386. PMID 19597008.

- Cornely OA, Maertens J, Winston DJ, Perfect J, Ullmann AJ, Walsh TJ, et al. (January 2007). "Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (4): 348–59. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061094. PMID 17251531.

- Kontoyiannis DP, Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, Chamilos G, Healy M, Perego C, Safdar A, Kantarjian H, Champlin R, Walsh TJ, Raad II (April 2005). "Zygomycosis in a tertiary-care cancer center in the era of Aspergillus-active antifungal therapy: a case-control observational study of 27 recent cases". J. Infect. Dis. 191 (8): 1350–60. doi:10.1086/428780. PMID 15776383.

- Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, et al. (February 2008). "Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clin. Infect. Dis. 46 (3): 327–60. doi:10.1086/525258. PMID 18177225.

- Herbrecht R, Denning D, Patterson T, Bennett J, Greene R, Oestmann J, et al. (8 August 2002). Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. "Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis". N Engl J Med. 347 (6): 408–15. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020191. hdl:2066/185528. PMID 12167683.

- Cornely OA, Maertens J, Bresnik M, Ebrahimi R, Ullmann AJ, Bouza E, et al. (May 2007). "Liposomal amphotericin B as initial therapy for invasive mold infection: a randomized trial comparing a high-loading dose regimen with standard dosing (AmBiLoad trial)". Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 (10): 1289–97. doi:10.1086/514341. PMID 17443465.

- Denning DW, Park S, Lass-Florl C, Fraczek MG, Kirwan M, Gore R, Smith J, Bueid A, Bowyer P, Perlin DS (2011). "High-frequency Triazole Resistance Found In Nonculturable Aspergillus fumigatus from Lungs of Patients with Chronic Fungal Disease". Clin Infect Dis. 52 (9): 1123–9. doi:10.1093/cid/cir179. PMC 3106268. PMID 21467016.

- Perea S, Patterson TF (November 2002). "Antifungal resistance in pathogenic fungi". Clin. Infect. Dis. 35 (9): 1073–80. doi:10.1086/344058. PMID 12384841.

- Bongomin, Felix; Gago, Sara; Oladele, Rita O.; Denning, David W. (18 October 2017). "Global and Multi-National Prevalence of Fungal Diseases-Estimate Precision". Journal of Fungi. 3 (4): 57. doi:10.3390/jof3040057. ISSN 2309-608X. PMC 5753159. PMID 29371573.

- Bongomin, Felix; Batac, C. R.; Richardson, Malcolm D.; Denning, David W. (2018). "A Review of Onychomycosis Due to Aspergillus Species". Mycopathologia. 183 (3): 485–493. doi:10.1007/s11046-017-0222-9. ISSN 1573-0832. PMC 5958150. PMID 29147866.

- "Aspergillus bronchitis | Aspergillus & Aspergillosis Website". www.aspergillus.org.uk.

- Durack, Juliana; Boushey, Homer A.; Lynch, Susan V. (2016). "Airway Microbiota and the Implications of Dysbiosis in Asthma". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 16 (8): 52. doi:10.1007/s11882-016-0631-8. ISSN 1534-6315. PMID 27393699.

- Anderson, Charles (2019-06-13). "World's fattest parrot, the endangered kākāpō, could be wiped out by fungal infection". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

Further reading

- Latgé JP (1999). "Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 12 (2): 310–350. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.2.310. PMC 88920. PMID 10194462. (Review).

- Sugui JA, Kwon-Chung KJ, Juvvadi PR, Latgé JP, Steinbach WJ (2015). "Aspergillus fumigatus and related species". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 5 (2): a019786. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019786. PMC 4315914. PMID 25377144. (Review)

External links

- USGS National Wildlife Health Center

- Aspergillus & Aspergillosis Website

- National Aspergillosis Centre, Manchester, UK

- Aspergillosis Community Website (primarily for patients and carers)

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |