Bacillus

Bacillus (Latin "stick") is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, a member of the phylum Firmicutes, with 266 named species. The term is also used to describe the shape (rod) of certain bacteria; and the plural Bacilli is the name of the class of bacteria to which this genus belongs. Bacillus species can be either obligate aerobes: oxygen dependent; or facultative anaerobes: having the ability to be anaerobic in the absence of oxygen. Cultured Bacillus species test positive for the enzyme catalase if oxygen has been used or is present.[2]

| Bacillus | |

|---|---|

| |

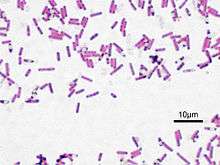

| Bacillus subtilis, Gram stained | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Firmicutes |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Bacillales |

| Family: | Bacillaceae |

| Genus: | Bacillus Cohn, 1872[1] |

| Species | |

Bacillus can reduce themselves to oval endospores and can remain in this dormant state for years. The endospore of one species from Morocco is reported to have survived being heated to 420 °C.[3] Endospore formation is usually triggered by a lack of nutrients: the bacterium divides within its cell wall, and one side then engulfs the other. They are not true spores (i.e., not an offspring).[4] Endospore formation originally defined the genus, but not all such species are closely related, and many species have been moved to other genera of the Firmicutes.[5] Only one endospore is formed per cell. The spores are resistant to heat, cold, radiation, desiccation, and disinfectants. Bacillus anthracis needs oxygen to sporulate; this constraint has important consequences for epidemiology and control. In vivo, B anthracis produces a polypeptide (polyglutamic acid) capsule that protects it from phagocytosis. The genera Bacillus and Clostridium constitute the family Bacillaceae. Species are identified by using morphologic and biochemical criteria. [6] Because the spores of many Bacillus species are resistant to heat, radiation, disinfectants, and desiccation, they are difficult to eliminate from medical and pharmaceutical materials and are a frequent cause of contamination. Bacillus species are well known in the food industries as troublesome spoilage organisms. [7]

Ubiquitous in nature, Bacillus includes both free-living (nonparasitic) species, and two parasitic pathogenic species. These two Bacillus species are medically significant: B. anthracis causes anthrax; and B. cereus causes food poisoning.

Many species of Bacillus can produce copious amounts of enzymes which are used in various industries, such as the production of alpha amylase used in starch hydrolysis, and the protease subtilisin used in detergents. B. subtilis is a valuable model for bacterial research. Some Bacillus species can synthesize and secrete lipopeptides, in particular surfactins and mycosubtilins.[8][9]

Life Cycle

Bacillus has a life cycle of spore forming. It entails 3 different processes. Vegetative growth, Sporulation, and Germination.

Vegetative Growth

Vegetative growth is characterized by binary symmetric fission cell growth that occurs when nutrients are available. Chromosomal replication is intimately tied to the vegetative cell division cycle (Wang and Levin 2009). The total separation of sister cells by cleavage of the cell wall in Bacillus species may not occur under some circumstances, and the cells may remain linked together through multiple rounds of binary fission, forming long chains (Branda et al., 2001, Chai et al., 2010, Kearns and Losick, 2005). Rosenberg et al. (2012) demonstrated transcriptional variability among different bacterial cells during vegetative growth directly related to nutrient availability, and this may represent an additional strategy to enhance population robustness.[10]

Sporulation

Multiple environmental signals, such as nutrient deprivation, high mineral composition, neutral pH, temperature, and high cell density can trigger the differentiation of vegetative cells into endospores. The cellular mass increases associated with the accumulation of secreted peptides are sensed by cell surface receptors that promote the sequential activation of the master regulator SpoA. This activation is called phosphorelay and involves the transference of phosphate groups from ATP through histidine kinases and two intermediate proteins, Spo0F and Spo0B, to a transcription factor, Spo0A. Spo0A-P controls the expression of a multitude of genes, setting off a chain of events that takes several hours to complete and culminates in the release of the mature spore from its mother cell compartment (Molle et al., 2003, Veening et al., 2009). However, the ultimate decision to sporulate is stochastic in that only a portion of the population sporulates, even under optimal conditions (Chastanet et al. 2010).[10]

The spore formation process (Fig. 2) is described by seven stages. Stage I: The nuclear material is disposed axially into filaments.

Stage II: Completion of DNA segregation occurs concurrently with the invagination of the plasmatic membrane in an asymmetric position, near one pole of the cell, forming a septum.

Stage III: The septum begins to curve, and the immature spore is surrounded by a double membrane of the mother cell in an engulfment process, similar to phagocytosis, and the smaller forespore becomes entirely contained within the mother cell.

Stage IV: The mother cell mediates the development of the forespore into the spore. The inner and outer proteinaceous layers of the spore are assembled, and the spore cortex, consisting of a thick layer of peptidoglycans contained between the inner and outer spore membranes, is synthesized. Furthermore, calcium dipicolinate accumulates in the nucleus.

Stage V: The spore coat is synthesized, consisting of ∼80 proteins deposited by the mother cell, and is arranged in inner and outer layers.

Stage VI: Spore maturation occurs during this stage, and the spores become resistant to heat and organic solvents.

Stage VII: Lytic enzymes disrupt the mother cell, releasing the mature spore (Errington, 2003, Higgins and Dworkin, 2012, Setlow, 2007).

Germination

Spores can remain dormant for extended time periods and possess a remarkable resistance to environmental damages, such as heat, radiation, toxic chemicals, and pH extremes. Under favorable environmental conditions, the spore breaks dormancy and restarts growth in a process called spore germination and outgrowth (Fig. 3). The germination process occurs in the following three stages: Stage I: Activation, defined as the initiation or triggering process in response to nutritional replenishment that occurs when the germinating molecules, including low-molecular-weight amino acids, sugars, and purine nucleosides, are sensed by germination receptors (GRs) located in the inner membrane of the spore. These receptors include, gerA, gerB, or gerK, and the germinating molecules bind these receptors. l-alanine acts through the gerA receptor, and a mixture of l-asparagine, fructose, glucose and KCl (AGFK) bind the gerB and gerK receptors. High hydrostatic pressures (HHPs) of 200–400 MPa also trigger germination through the GRs. The germinating spore initially releases H+, K+, Na+ and Ca+2, raising the pH of the spore core from pH 6.5 to 7.7. Cortex lytic enzymes are activated, and the protective spore peptidoglycan cortex is degraded. Activation is a reversible process that does not necessarily commit the spore to germination and outgrowth (Setlow, 2003, Paredes-Sabja et al., 2011, Stewart and Setlow, 2013).

Stage II: DPA (pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid) is degraded and released, followed by rehydration of the spore core. Rehydration allows the initiation of protein mobility and reactivation of biochemical processes during outgrowth (Zhang et al. 2010).

Stage III: Spore coat hydrolysis allows the emergence of the incipient vegetative cell.[10]

- vegetative growth

- binary fission of bacteria, some may produce a new set of genes

- sporulation

- the formation of new spores in bacteria

- germination

- start of metabolic activity, spores than return to the vegetative growth stage

Structure

Cell wall

The cell wall of Bacillus is a structure on the outside of the cell that forms the second barrier between the bacterium and the environment, and at the same time maintains the rod shape and withstands the pressure generated by the cell's turgor. The cell wall is composed of teichoic and teichuronic acids. B. subtilis is the first bacterium for which the role of an actin-like cytoskeleton in cell shape determination and peptidoglycan synthesis was identified, and for which the entire set of peptidoglycan-synthesizing enzymes was localised. The role of the cytoskeleton in shape generation and maintenance is important.

Bacillus species are rod-shaped, endospore-forming aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, Gram-positive bacteria; in some species cultures may turn Gram-negative with age. The many species of the genus exhibit a wide range of physiologic abilities that allow them to live in every natural environment. Only one endospore is formed per cell. The spores are resistant to heat, cold, radiation, desiccation, and disinfectants. [11]

How Bacillus got its name

The genus Bacillus was named in 1835 by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, to contain rod-shaped (bacillus) bacteria. He had seven years earlier named the genus Bacterium. Bacillus was later amended by Ferdinand Cohn to further describe them as spore-forming, Gram-positive, aerobic or facultatively anaerobic bacteria.[1] Like other genera associated with the early history of microbiology, such as Pseudomonas and Vibrio, the 266 species of Bacillus are ubiquitous.[12] The genus has a very large ribosomal 16S diversity.

Isolation and identification

An easy way to isolate Bacillus species is by placing nonsterile soil in a test tube with water, shaking, placing in melted mannitol salt agar, and incubating at room temperature for at least a day. Cultured colonies are usually large, spreading, and irregularly shaped.

Under the microscope, the Bacillus cells appear as rods, and a substantial portion of the cells usually contain oval endospores at one end, making them bulge.

Phylogeny

Three proposals have been presented as representing the phylogeny of the genus Bacillus. The first proposal, presented in 2003, is a Bacillus-specific study, with the most diversity covered using 16S and the ITS regions. It divides the genus into 10 groups. This includes the nested genera Paenibacillus, Brevibacillus, Geobacillus, Marinibacillus and Virgibacillus.[13]

The second proposal, presented in 2008,[14] constructed a 16S (and 23S if available) tree of all validated species.[15][16] The genus Bacillus contains a very large number of nested taxa and majorly in both 16S and 23S. It is paraphyletic to the Lactobacillales (Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Listeria, etc.), due to Bacillus coahuilensis and others.

A third proposal, presented in 2010, was a gene concatenation study, and found results similar to the 2008 proposal, but with a much more limited number of species in terms of groups.[17] (This scheme used Listeria as an outgroup, so in light of the ARB tree, it may be "inside-out").

One clade, formed by Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus mycoides, Bacillus pseudomycoides, Bacillus thuringiensis, and Bacillus weihenstephanensis under the 2011 classification standards, should be a single species (within 97% 16S identity), but due to medical reasons, they are considered separate species[18]:34–35 (an issue also present for four species of Shigella and Escherichia coli).[19]

| Bacillus phylogenetics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny of the genus Bacillus according to [17] |

Species

- B. acidiceler

- B. acidicola

- B. acidiproducens

- B. acidocaldarius

- B. acidoterrestris

- B. aeolius

- B. aerius

- B. aerophilus

- B. agaradhaerens

- B. agri

- B. aidingensis

- B. akibai

- B. alcalophilus

- B. algicola

- B. alginolyticus

- B. alkalidiazotrophicus

- B. alkalinitrilicus

- B. alkalisediminis

- B. alkalitelluris

- B. altitudinis

- B. alveayuensis

- B. alvei

- B. amyloliquefaciens

- B. a. subsp. amyloliquefaciens

- B. a. subsp. plantarum

- B. aminovorans[20]

- B. amylolyticus

- B. andreesenii

- B. aneurinilyticus

- B. anthracis

- B. aquimaris

- B. arenosi

- B. arseniciselenatis

- B. arsenicus

- B. aurantiacus

- B. arvi

- B. aryabhattai

- B. asahii

- B. atrophaeus

- B. axarquiensis

- B. azotofixans

- B. azotoformans

- B. badius

- B. barbaricus

- B. bataviensis

- B. beijingensis

- B. benzoevorans

- B. beringensis

- B. berkeleyi

- B. beveridgei

- B. bogoriensis

- B. boroniphilus

- B. borstelensis

- B. brevis Migula

- B. butanolivorans

- B. canaveralius

- B. carboniphilus

- B. cecembensis

- B. cellulosilyticus

- B. centrosporus

- B. cereus

- B. chagannorensis

- B. chitinolyticus

- B. chondroitinus

- B. choshinensis

- B. chungangensis

- B. cibi

- B. circulans

- B. clarkii

- B. clausii

- B. coagulans

- B. coahuilensis

- B. cohnii

- B. composti

- B. curdlanolyticus

- B. cycloheptanicus

- B. cytotoxicus

- B. daliensis

- B. decisifrondis

- B. decolorationis

- B. deserti

- B. dipsosauri

- B. drentensis

- B. edaphicus

- B. ehimensis

- B. eiseniae

- B. enclensis

- B. endophyticus

- B. endoradicis

- B. farraginis

- B. fastidiosus

- B. fengqiuensis

- B. firmus

- B. flexus

- B. foraminis

- B. fordii

- B. formosus

- B. fortis

- B. fumarioli

- B. funiculus

- B. fusiformis

- B. galactophilus

- B. galactosidilyticus

- B. galliciensis

- B. gelatini

- B. gibsonii

- B. ginsengi

- B. ginsengihumi

- B. ginsengisoli

- B. glucanolyticus

- B. gordonae

- B. gottheilii

- B. graminis

- B. halmapalus

- B. haloalkaliphilus

- B. halochares

- B. halodenitrificans

- B. halodurans

- B. halophilus

- B. halosaccharovorans

- B. hemicellulosilyticus

- B. hemicentroti

- B. herbersteinensis

- B. horikoshii

- B. horneckiae

- B. horti

- B. huizhouensis

- B. humi

- B. hwajinpoensis

- B. idriensis

- B. indicus

- B. infantis

- B. infernus

- B. insolitus

- B. invictae

- B. iranensis

- B. isabeliae

- B. isronensis

- B. jeotgali

- B. kaustophilus

- B. kobensis

- B. kochii

- B. kokeshiiformis

- B. koreensis

- B. korlensis

- B. kribbensis

- B. krulwichiae

- B. laevolacticus

- B. larvae

- B. laterosporus

- B. lautus

- B. lehensis

- B. lentimorbus

- B. lentus

- B. licheniformis

- B. ligniniphilus

- B. litoralis

- B. locisalis

- B. luciferensis

- B. luteolus

- B. luteus

- B. macauensis

- B. macerans

- B. macquariensis

- B. macyae

- B. malacitensis

- B. mannanilyticus

- B. marisflavi

- B. marismortui

- B. marmarensis

- B. massiliensis

- B. megaterium

- B. mesonae

- B. methanolicus

- B. methylotrophicus

- B. migulanus

- B. mojavensis

- B. mucilaginosus

- B. muralis

- B. murimartini

- B. mycoides

- B. naganoensis

- B. nanhaiensis

- B. nanhaiisediminis

- B. nealsonii

- B. neidei

- B. neizhouensis

- B. niabensis

- B. niacini

- B. novalis

- B. oceanisediminis

- B. odysseyi

- B. okhensis

- B. okuhidensis

- B. oleronius

- B. oryzaecorticis

- B. oshimensis

- B. pabuli

- B. pakistanensis

- B. pallidus

- B. pallidus

- B. panacisoli

- B. panaciterrae

- B. pantothenticus

- B. parabrevis

- B. paraflexus

- B. pasteurii

- B. patagoniensis

- B. peoriae

- B. persepolensis

- B. persicus

- B. pervagus

- B. plakortidis

- B. pocheonensis

- B. polygoni

- B. polymyxa

- B. popilliae

- B. pseudalcalophilus

- B. pseudofirmus

- B. pseudomycoides

- B. psychrodurans

- B. psychrophilus

- B. psychrosaccharolyticus

- B. psychrotolerans

- B. pulvifaciens

- B. pumilus

- B. purgationiresistens

- B. pycnus

- B. qingdaonensis

- B. qingshengii

- B. reuszeri

- B. rhizosphaerae

- B. rigui

- B. ruris

- B. safensis

- B. salarius

- B. salexigens

- B. saliphilus

- B. schlegelii

- B. sediminis

- B. selenatarsenatis

- B. selenitireducens

- B. seohaeanensis

- B. shacheensis

- B. shackletonii

- B. siamensis

- B. silvestris

- B. simplex

- B. siralis

- B. smithii

- B. soli

- B. solimangrovi

- B. solisalsi

- B. songklensis

- B. sonorensis

- B. sphaericus

- B. sporothermodurans

- B. stearothermophilus

- B. stratosphericus

- B. subterraneus

- B. subtilis

- B. s. subsp. inaquosorum

- B. s. subsp. spizizenii

- B. s. subsp. subtilis

- B. taeanensis

- B. tequilensis

- B. thermantarcticus

- B. thermoaerophilus

- B. thermoamylovorans

- B. thermocatenulatus

- B. thermocloacae

- B. thermocopriae

- B. thermodenitrificans

- B. thermoglucosidasius

- B. thermolactis

- B. thermoleovorans

- B. thermophilus

- B. thermoruber

- B. thermosphaericus

- B. thiaminolyticus

- B. thioparans

- B. thuringiensis

- B. tianshenii

- B. trypoxylicola

- B. tusciae

- B. validus

- B. vallismortis

- B. vedderi

- B. velezensis

- B. vietnamensis

- B. vireti

- B. vulcani

- B. wakoensis

- B. xiamenensis

- B. xiaoxiensis

- B. zhanjiangensis

Ecological and Clinical significance, Signs and Symptoms

Bacillus species are ubiquitous in nature, e.g. in soil. They can occur in extreme environments such as high pH (B. alcalophilus), high temperature (B. thermophilus), and high salt concentrations (B. halodurans). B. thuringiensis produces a toxin that can kill insects and thus has been used as insecticide.[21] B. siamensis has antimicrobial compounds that inhibit plant pathogens, such as the fungi Rhizoctonia solani and Botrytis cinerea, and they promote plant growth by volatile emissions.[22] Some species of Bacillus are naturally competent for DNA uptake by transformation.[23]

- Two Bacillus species are medically significant: B. anthracis, which causes anthrax; and B. cereus, which causes food poisoning, with symptoms similar to that caused by Staphylococcus.[24]

- B. Cereus produces toxins which cause 2 different set of symptoms

- emetic toxin which can cause vomiting and nausea

- diarrhea

- B. Cereus produces toxins which cause 2 different set of symptoms

- B. thuringiensis is an important insect pathogen, and is sometimes used to control insect pests.

- B. subtilis is an important model organism. It is also a notable food spoiler, causing ropiness in bread and related food.

- B. Subtilis can also produce and secrete antibiotics.

- Some environmental and commercial strains of B. coagulans may play a role in food spoilage of highly acidic, tomato-based products.

Anthrax and Symptoms

Anthrax is primarily a disease of herbivores. Humans acquire it as a result of contact with infected animals or animal products. In humans the disease takes one of three forms, depending on the route of infection. Cutaneous anthrax, which accounts for more than 95 percent of cases worldwide, results from infection through skin lesions; intestinal anthrax results from ingestion of spores, usually in infected meat; and pulmonary anthrax results from inhalation of spores. [25]

Cutaneous Anthrax Cutaneous anthrax usually occurs through contamination of a cut or abrasion. It's by far the most common route the disease takes. It's also the mildest — with appropriate treatment, cutaneous anthrax is seldom fatal. Signs and symptoms of cutaneous anthrax include: [26]

- A raised, itchy bump resembling an insect bite that quickly develops into a painless sore with a black center

- Swelling in the sore and nearby lymph glands

Gastrointestinal Anthrax[27] This form of anthrax infection begins by eating undercooked meat from an infected animal. Signs and symptoms include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Headache

- Loss of appetite

- Fever

- Severe, bloody diarrhea in the later stages of the disease

- Sore throat and difficulty swallowing

- Swollen neck

Pulmonary Anthrax [28] Inhalation anthrax develops when you breathe in anthrax spores. It's the most deadly way to contract the disease, and even with treatment, it is often fatal. Initial signs and symptoms of inhalation anthrax include:

-Flu-like symptoms, such as sore throat, mild fever, fatigue and muscle aches, which may last a few hours or days

-Mild chest discomfort

-Shortness of breath

-Nausea

-Coughing up blood

-Painful swallowing

As the disease progresses, you may experience:

- High fever

- Trouble breathing

- Shock

- Meningitis — a potentially life-threatening inflammation of the brain and spinal cord

Industrial significance

Many Bacillus species are able to secrete large quantities of enzymes. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens is the source of a natural antibiotic protein barnase (a ribonuclease), alpha amylase used in starch hydrolysis, the protease subtilisin used with detergents, and the BamH1 restriction enzyme used in DNA research.

A portion of the Bacillus thuringiensis genome was incorporated into corn (and cotton) crops. The resulting GMOs are resistant to some insect pests.Bacillus species continue to be dominant bacterial workhorses in microbial fermentations. Bacillus subtilis (natto) is the key microbial participant in the ongoing production of the soya-based traditional natto fermentation, and some Bacillus species are on the Food and Drug Administration's GRAS (generally regarded as safe) list. The capacity of selected Bacillus strains to produce and secrete large quantities (20-25 g/L) of extracellular enzymes has placed them among the most important industrial enzyme producers. The ability of different species to ferment in the acid, neutral, and alkaline pH ranges, combined with the presence of thermophiles in the genus, has led to the development of a variety of new commercial enzyme products with the desired temperature, pH activity, and stability properties to address a variety of specific applications. Classical mutation and (or) selection techniques, together with advanced cloning and protein engineering strategies, have been exploited to develop these products. Efforts to produce and secrete high yields of foreign recombinant proteins in Bacillus hosts initially appeared to be hampered by the degradation of the products by the host proteases. Recent studies have revealed that the slow folding of heterologous proteins at the membrane-cell wall interface of Gram-positive bacteria renders them vulnerable to attack by wall-associated proteases. In addition, the presence of thiol-disulphide oxidoreductases in B. subtilis may be beneficial in the secretion of disulphide-bond-containing proteins. Such developments from our understanding of the complex protein translocation machinery of Gram-positive bacteria should allow the resolution of current secretion challenges and make Bacillus species preeminent hosts for heterologous protein production. Bacillus strains have also been developed and engineered as industrial producers of nucleotides, the vitamin riboflavin, the flavor agent ribose, and the supplement poly-gamma-glutamic acid. With the recent characterization of the genome of B. subtilis 168 and of some related strains, Bacillus species are poised to become the preferred hosts for the production of many new and improved products as we move through the genomic and proteomic era. [29]

Use as model organism

Bacillus subtilis is one of the best understood prokaryotes, in terms of molecular and cellular biology. Its superb genetic amenability and relatively large size have provided the powerful tools required to investigate a bacterium from all possible aspects. Recent improvements in fluorescent microscopy techniques have provided novel insight into the dynamic structure of a single cell organism. Research on B. subtilis has been at the forefront of bacterial molecular biology and cytology, and the organism is a model for differentiation, gene/protein regulation, and cell cycle events in bacteria.[30]

See also

- Paenibacillus and Virgibacillus, genera of bacteria formerly included in Bacillus.[31][32]

References

- (in German) Cohn F.: Untersuchungen über Bakterien. Beitrage zur Biologie der Pflanzen Heft 2, 1872, 1, 127–224.

- Turnbull PCB (1996). "Bacillus". In Baron S; et al. (eds.). Bacillus. In: Barron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2.

- "Turn up the Heat: Bacterial Spores Can Take Temperatures in the Hundreds of Degrees".

- "Bacterial Endospores". Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Department of Microbiology. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- Madigan M; Martinko J, eds. (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-144329-7.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7699/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7699/

- Nigris, Sebastiano; Baldan, Enrico; Tondello, Alessandra; Zanella, Filippo; Vitulo, Nicola; Favaro, Gabriella; Guidolin, Valerio; Bordin, Nicola; Telatin, Andrea; Barizza, Elisabetta; Marcato, Stefania; Zottini, Michela; Squartini, Andrea; Valle, Giorgio; Baldan, Barbara (2018). "Biocontrol traits of Bacillus licheniformis GL174, a culturable endophyte of Vitis vinifera cv. Glera". BMC Microbiology. 18 (1): 133. doi:10.1186/s12866-018-1306-5. PMC 6192205. PMID 30326838.

- Favaro, Gabriella; Bogialli, Sara; Di Gangi, Iole Maria; Nigris, Sebastiano; Baldan, Enrico; Squartini, Andrea; Pastore, Paolo; Baldan, Barbara (2016). "Characterization of lipopeptides produced by Bacillus licheniformisusing liquid chromatography with accurate tandem mass spectrometry". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 30 (20): 2237–2252. doi:10.1002/rcm.7705. PMID 27487987.

- Sella, Sandra R.B.R.; Vandenberghe, Luciana P.S.; Soccol, Carlos Ricardo (December 2014). "Life cycle and spore resistance of spore-forming Bacillus atrophaeus". Microbiological Research. 169 (12): 931–939. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2014.05.001. PMID 24880805.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7699/

- Bacillus entry in LPSN [Euzéby, J.P. (1997). "List of Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature: a folder available on the Internet". Int J Syst Bacteriol. Microbiology Society. 47 (2): 590–2. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-2-590. ISSN 0020-7713. PMID 9103655. Retrieved 2019-02-23.]

- Xu, D.; Cote, J. -C. (2003). "Phylogenetic relationships between Bacillus species and related genera inferred from comparison of 3' end 16S rDNA and 5' end 16S-23S ITS nucleotide sequences". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (3): 695–704. doi:10.1099/Ijs.0.02346-0. PMID 12807189.

- http://www.arb-silva.de/fileadmin/silva_databases/living_tree/LTP_release_104/LTPs104_SSU_tree.pdf

- Yarza, P.; Richter, M.; Peplies, J. R.; Euzeby, J.; Amann, R.; Schleifer, K. H.; Ludwig, W.; Glöckner, F. O.; Rosselló-Móra, R. (2008). "The All-Species Living Tree project: A 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of all sequenced type strains". Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 31 (4): 241–250. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2008.07.001. hdl:10261/103580. PMID 18692976.

- Yarza, P.; Ludwig, W.; Euzéby, J.; Amann, R.; Schleifer, K. H.; Glöckner, F. O.; Rosselló-Móra, R. (2010). "Update of the All-Species Living Tree Project based on 16S and 23S rRNA sequence analyses". Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 33 (6): 291–299. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2010.08.001. hdl:10261/54801. PMID 20817437.

- Alcaraz, L.; Moreno-Hagelsieb, G.; Eguiarte, L. E.; Souza, V.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Olmedo, G. (2010). "Understanding the evolutionary relationships and major traits of Bacillus through comparative genomics". BMC Genomics. 11: 332. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-332. PMC 2890564. PMID 20504335. 1471216411332.

- Ole Andreas Økstad and Anne-Brit Kolstø Chapter 2: "Genomics of Bacillus Species" in M. Wiedmann, W. Zhang (eds.), Genomics of Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens, 29 Food Microbiology and Food Safety. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7686-4_2

- Brenner (D.J.): Family I. Enterobacteriaceae Rahn 1937, Nom. fam. cons. Opin. 15, Jud. Com. 1958, 73; Ewing, Farmer, and Brenner 1980, 674; Judicial Commission 1981, 104. In: N.R. Krieg and J.G. Holt (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, first edition, vol. 1, The Williams & Wilkins Co, Baltimore, 1984, pp. 408-420

- Loshon, Charles A.; Beary, Katherine E.; Gouveia, Kristine; Grey, Elizabeth Z.; Santiago-Lara, Leticia M.; Setlow, Peter (March 1998). "Nucleotide sequence of the sspE genes coding for γ-type small, acid-soluble spore proteins from the round-spore-forming bacteria Bacillus aminovorans, Sporosarcina halophila and S. ureae". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Structure and Expression. 1396 (2): 148–152. doi:10.1016/S0167-4781(97)00204-2. PMID 9540829.

- Joan L. Slonczewski & John W. Foster (2011), Microbiology: An Evolving Science (2nd Edition), Norton

- Jeong, Haeyoung; Jeong, Da-Eun; Kim, Sun Hong; Song, Geun Cheol; Park, Soo-Young; Ryu, Choong-Min; Park, Seung-Hwan; Choi, Soo-Keun (2012-08-01). "Draft Genome Sequence of the Plant Growth-Promoting Bacterium Bacillus siamensis KCTC 13613T". Journal of Bacteriology. 194 (15): 4148–4149. doi:10.1128/JB.00805-12. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 3416560. PMID 22815459.

- Keen, E; Bliskovsky, V; Adhya, S; Dantas, G (2017). "Draft genome sequence of the naturally competent Bacillus simplex strain WY10". Genome Announcements. 5 (46): e01295–17. doi:10.1128/genomeA.01295-17. PMC 5690344. PMID 29146837.

- Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7699/

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anthrax/symptoms-causes/syc-20356203

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anthrax/symptoms-causes/syc-20356203

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anthrax/symptoms-causes/syc-20356203

- Schallmey, M.; Singh, A.; Ward, O. P. (2004). "Developments in the use of Bacillus species for industrial production". Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 50 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1139/w03-076. PMID 15052317.

- Graumann P, ed. (2012). Bacillus: Cellular and Molecular Biology (2nd ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-97-4. .

- Ash, Carol; Priest, Fergus G.; Collins, M. David (1994). "Molecular identification of rRNA group 3 bacilli (Ash, Farrow, Wallbanks and Collins) using a PCR probe test". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 64 (3–4): 253–260. doi:10.1007/BF00873085. PMID 8085788.

- Heyndrickx, M.; Lebbe, L.; Kersters, K.; De Vos, P.; Forsyth, G.; Logan, N. A. (1 January 1998). "Virgibacillus: a new genus to accommodate Bacillus pantothenticus (Proom and Knight 1950). Emended description of Virgibacillus pantothenticus". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 48 (1): 99–106. doi:10.1099/00207713-48-1-99.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bacillus. |