Multi-Component Worksite Obesity Prevention

What is multi-component worksite obesity prevention?

Selected Resources

Worksite nutrition and physical activity programs are designed to improve health-related behaviors and outcomes among employees.[1] Employers may offer worksite weight control interventions separately or as part of a comprehensive wellness package that addresses multiple health issues (e.g., smoking cessation, stress management, cholesterol reduction).[2] Worksite strategies can include one or more approaches to support behavioral change including:

- Informational and educational strategies to increase knowledge about a healthy diet, such as lectures, written materials (electronic or print), or educational software.[2]

- Behavioral and social strategies to support positive beliefs and social factors, such as counseling, skill-building, rewards or reinforcement, and building support systems.[2]

- Environmental approaches that make healthy choices easier and target the entire workforce by changing physical or organizational structures. They may include improving access to healthy foods and providing opportunities to be more physically active at work.[2]

- Policy strategies may change rules and procedures for employees such as health insurance benefits or cash incentives for health club membership.[2]

Worksite obesity prevention may be implemented by employers in both the public and private sectors. Moving toward this goal, Ohio has included strategies such as education and environmental approaches to improve physical activity, nutrition, and overall health, to promote health and wellness among all of its state employees in its state obesity prevention plan.[3]

What is the public health issue?

Obesity is common, serious, and costly. Obesity is related to several leading causes of death, including heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer.[4, 5] Data from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) show that more than one-third (36.5 percent) of U.S. adults are obese.[6] Obesity affects some groups more than others. Non-Hispanic blacks have the highest age-adjusted rates of obesity (48.1 percent) followed by Hispanics (42.5 percent), non-Hispanic whites (34.5 percent), and non-Hispanic Asians (11.7 percent).[6] Obesity is also more common among middle-aged adults 40 to 59 years old (40.2 percent) than adults 60 years or older (37 percent) or younger adults aged 20 to 39 years (32.3 percent).[6]

The estimated annual medical cost of obesity in the U.S. was $147 billion in 2008 dollars.[4, 7] Obesity-related medical expenditures, absenteeism, and reduced productivity while at work among full-time U.S. employees is estimated to cost over $73 billion annually.[8]

What is the evidence of health impact and cost effectiveness?

Studies examining the effectiveness of multi-component worksite obesity prevention and control programs, including a systematic review[1], meta-analysis[9], and randomized control trial[10], found that programs were consistently associated with:

- Increased physical activity [9, 10]

- Reductions in weight [1, 9]

- Reductions in percentage of body fat [9]

- Reductions in BMI [1]

A literature review examining worksite nutritional interventions found that such strategies were associated with positive effects on employee nutrition and health, as well as improved employee productivity and reduced absenteeism.[11] A study examining a workplace behavioral weight management program with monetary incentives compared to a non-incentivized program found, among both groups, weight loss among obese and overweight employees and also net savings for employers primarily due to increased productivity, with significantly larger effects among the incentivized participants.[12] Another study that assessed the return on investment to employers for workplace obesity interventions found that a 5 percent weight loss among overweight and obese employees would result in an average per person reduction of $90 due to reductions in medical costs and absenteeism costs.[13]

A systematic review on the financial return of worksite health promotion programs aimed at generally improving nutrition or increasing physical activity found positive impacts among the 13 non-randomized studies (NRS) included in the review, and negative impacts among the 4 randomized control trials (RCT). However, 3 of the RCTs and 1 NRS were conducted outside the U.S. and no adjustments were made to account for the differences in medical costs between countries.[14]

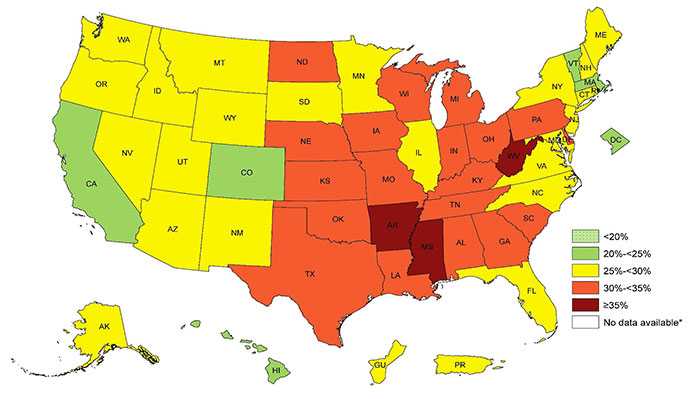

Prevalence of Self-Reported Obesity among U.S. Adults by State and Territory, BRFSS, 2014 [4]

For questions or additional information, email healthpolicynews@cdc.gov.

References

- Anderson, L.M., et al., The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: a systematic review. American journal of preventive medicine, 2009. 37(4): p. 340-357.

- The Guide to Community Preventive Services, Obesity Prevention and Control: Worksite Programs. The Community Guide: What Works to Promote Health 2007 August 14, 2015 [cited 2015 November 25]; Available from: Obesity Prevention and Control: Worksite Programs.

- Ohio Department of Health, The Ohio Obesity Prevention Plan, 2009: Columbus, OH. Available from: The Ohio Obesity Prevention Plan

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Adult Obesity Facts, September 21, 2015 [cited 2015 November 25]; Available from: Adult Obesity Facts.

- U.S. Department of Health Human Services, Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report, NIH Publication No. 98-4083, 1998.

- Ogden, C.L., et al., Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS data brief, 2015. 219(219): p. 1-8.

- Finkelstein, E.A., et al., Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health affairs, 2009. 28(5): p. w822-w831.

- Finkelstein, E.A., et al., The costs of obesity in the workplace. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2010. 52(10): p. 971-976.

- Verweij, L., et al., Meta‐analyses of workplace physical activity and dietary behaviour interventions on weight outcomes. Obesity Reviews, 2011. 12(6): p. 406-429.

- Dishman, R.K., et al., Move to improve: a randomized workplace trial to increase physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2009. 36(2): p. 133-141.

- Jensen, J.D., Can worksite nutritional interventions improve productivity and firm profitability? A literature review. Perspectives in Public Health, 2011. 131(4): p. 184-192.

- Lahiri, S. and P.D. Faghri, Cost-effectiveness of a workplace-based incentivized weight loss program. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2012. 54(3): p. 371-377.

- Trogdon, J., et al., A return-on-investment simulation model of workplace obesity interventions. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2009. 51(7): p. 751-758.

- Van Dongen, J., et al., Systematic review on the financial return of worksite health promotion programmes aimed at improving nutrition and/or increasing physical activity. Obesity Reviews, 2011. 12(12): p. 1031-1049.

- Page last reviewed: August 5, 2016

- Page last updated: August 5, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir