Health Impact in 5 Years

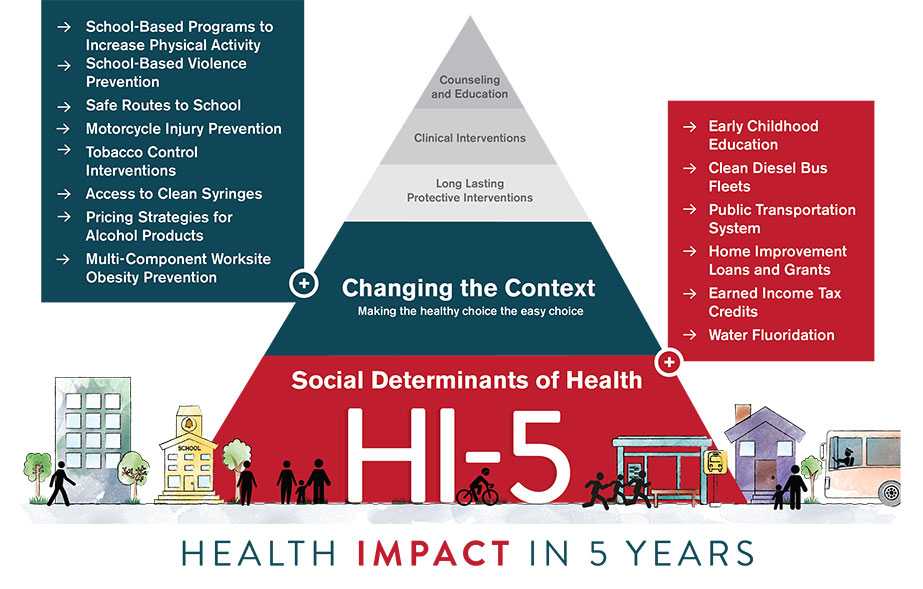

Achieving lasting impact on health outcomes requires a focus not just on patient care, but on community wide-approaches aimed at improving population health.[1-6] Interventions that address the conditions in the places where we live, learn, work, and play have the greatest potential impact on our health.[7-11] By focusing on these “social determinants of health” (SDOH) and on “changing the context to make healthy choices easier,” we can help improve the health of everyone living in a community.

The Health Impact in 5 Years (HI-5) initiative highlights non-clinical, community-wide approaches that have evidence reporting 1) positive health impacts, 2) results within five years, and 3) cost effectiveness and/or cost savings over the lifetime of the population or earlier.

HI-5 Resources

- View and download slides about HI-5 and the 14 evidence-based community-wide interventions.

- Download a printable version of the HI-5 Overview.

The public health impact pyramid visually depicts the potential impact of different types of public health interventions.[7] At the base of the pyramid are those interventions that have the greatest potential for impact on health because they reach entire populations of people at once and require less individual effort. The HI-5 Initiative maps directly to the two lowest tiers of public health pyramid with the greatest potential for impact.

Health conditions that the HI-5 interventions address

Community-wide approaches can have broad health impact, often addressing several health conditions at once. Below is a list of the health outcomes that HI-5 interventions can prevent or reduce:

- Anxiety and Depression

- Asthma

- Blood Pressure

- Bronchitis

- Cancer

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Child Abuse and Neglect

- Cognitive Development

- Infant Mortality

- Liver Cirrhosis

- Motor Vehicle Injuries

- Obesity

- Dental Caries

- Pneumonia

- Sexually Transmittable Infections

- Sexual Violence

- Teenage Pregnancy

- Traumatic Brain Injury

- Type II Diabetes

- Youth Violence

References

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County health rankings & roadmaps: housing rehabilitation loan & grant programs. 2015. Available from: Housing rehabilitation loan & grant programs. Accessed 2015 Nov 30.

- Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development. EmPOWER Maryland Low Income Energy Efficiency Program. 2016. Available from: EmPOWER Maryland Low Income Energy Efficiency Program. Accessed 2016 Jun 14.

- Minnesota Housing Finance Agency. Rehabilitation Loan/Emergency and Accessibility Loan Program. 2016. Available from: Rehabilitation Loan/Emergency and Accessibility Loan Program. Accessed 2016 Jun 14.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rural development. Single family housing repair loans & grants 2016. Available from: Single Family Housing Repair Loans & Grants. Accessed 2016 Jun 14.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 203(k) rehabilitation mortgage insurance. 2016. Available from: 203(k) Rehabilitation Mortgage Insurance. Accessed 2016 Jun 14.

- Gibson M, Petticrew M, Bambra C, Sowden AJ, Wright KE, Whitehead M. Housing and health inequalities: a synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at different pathways linking housing and health. Health & Place 2011; 17(1):175–84.

- Pollack C, Egerter S, Sadegh-Mobari T, Dekker M, Braveman P. Where we live matters for our health: the links between housing and health. In: Issue Brief 2: Housing and Health. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Commission to Build a Healthier America; 2008.

- Klepeis NE, Nelson WC, Ott WR, et al. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 2001;11(3):231–52.

- Shaw M. Housing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health 2004;25:397–418.

- Institute of Medicine. Damp indoor spaces and health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004.

- Thomson H, Thomas S. Developing empirically supported theories of change for housing investment and health. Soc Sci Med 2015;124:205–14.

- Breysse J, Jacobs DE, Weber W, et al. Health outcomes and green renovation of affordable housing. Public Health Rep 2011;126(Suppl 1):64–75.

- Jacobs DE, Breysse J, Dixon SL, et al. Health and housing outcomes from green renovation of low-income housing in Washington, DC. J Environ Health 2014;76(7):8–16, 60.

- Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E, Petticrew M. The health impacts of housing improvement: a systematic review of intervention studies from 1887 to 2007. Am J Public Health 2009;99(S3):S681–92.

- Howden-Chapman P, Matheson A, Crane J, et al. Effect of insulating existing houses on health inequality: cluster randomised study in the community. BMJ 2007;334(7591):460.

- Chapman R, Howden-Chapman P, VIggers H, O’Dea D, Kennedy M. Retrofitting houses with insulation: a cost-benefit analysis of a randomised community trial. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63(4):271–7.

- Page last reviewed: October 21, 2016

- Page last updated: October 21, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir