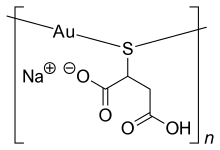

Sodium aurothiomalate

Sodium aurothiomalate (INN, known in the United States as gold sodium thiomalate) is a gold compound that is used for its immunosuppressive anti-rheumatic effects.[2][3] Along with an orally-administered gold salt, auranofin, it is one of only two gold compounds currently employed in modern medicine.[4]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Myocrisin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Multum Consumer Information |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | High[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 6-25 days[1] |

| Excretion | Urine (60-90%), faeces (10-40%)[1] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.032.242 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C4H4AuNaO4S |

| Molar mass | 367.939350590 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Medical uses

It is primarily given once or twice weekly by intramuscular injection for moderate-severe rheumatoid arthritis although it has also proven itself effective in treating tuberculosis.[5]

Adverse effects

Its most common side effects are digestive (mostly dyspepsia, mouth swelling, nausea, vomiting and taste disturbance), vasomotor (mostly flushing, fainting, dizziness, sweating, weakness, palpitations, shortness of breath and blurred vision) or dermatologic (usually itchiness, rash, local irritation near to the injection site and hair loss) in nature, although conjunctivitis, blood dyscrasias, kidney damage, joint pain, muscle aches/pains and liver dysfunction are also common.[6] Less commonly, it can cause GI bleeds, dry mucous membranes and gingivitis.[6] Rarely it can cause: aplastic anaemia, ulcerative enterocolitis, difficulty swallowing, angiooedema, pneumonitis, pulmonary fibrosis, hepatotoxicity, cholestatic jaundice, peripheral neuropathy, Guillain–Barré syndrome, encephalopathy, encephalitis and photosensitivity.[6]

Pharmacology

Its precise mechanism of action is unknown but is known that it inhibits the synthesis of prostaglandins.[4] It also modulates phagocytic cells and inhibits class II major histocompatibility complex-peptide interactions.[4] It is also known that it inhibits the following enzymes:[4][7]

History of use

Reports of favorable use of the compound were published in France in 1929 by Jacques Forestier.[9] The use of gold salts was then a controversial treatment and was not immediately accepted by the international community. Success was found in the treatment of Raoul Dufy's joint pain by the use of gold salts in 1940; "(The treatment) brought in a few weeks such a spectacular sense of healing, that Dufy ... boasted of again having the ability to catch a tram on the move." [10]

It was recently discontinued from the US market along with aurothioglucose leaving only auranofin as the only gold salt on the US market.

References

- "aurothiomalate, sodium, Myochrysine (gold sodium thiomalate) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- Jessop, J. D.; O'Sullivan, M. M.; Lewis, P. A.; Williams, L. A.; Camilleri, J. P.; Plant, M. J.; Coles, E. C. (1998). "A long-term five-year randomized controlled trial of hydroxychloroquine, sodium aurothiomalate, auranofin and penicillamine in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis". British Journal of Rheumatology. 37 (9): 992–1002. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/37.9.992. PMID 9783766.

- Iqbal, M. S.; Saeed, M.; Taqi, S. G. (2008). "Erythrocyte Membrane Gold Levels After Treatment with Auranofin and Sodium Aurothiomalate". Biological Trace Element Research. 126 (1–3): 56–64. doi:10.1007/s12011-008-8184-x. PMID 18649049.

- Kean, WF; Kean, IRL (4 June 2008). "Clinical pharmacology of gold". Inflammopharmacology. 16 (3): 112–125. doi:10.1007/s10787-007-0021-x. PMID 18523733.

- Benedek, TG (January 2004). "The history of gold therapy for tuberculosis". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 59 (1): 50–89. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrg042. PMID 15011812.

- Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- Berners-Price, SJ; Filipovska, A (September 2011). "Gold compounds as therapeutic agents for human diseases". Metallomics. 3 (9): 863–73. doi:10.1039/c1mt00062d. PMID 21755088.

- Tuure, L; Hämäläinen, M; Moilanen, T; Moilanen, E (2014). "Aurothiomalate inhibits the expression of mPGES-1 in primary human chondrocytes". Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 44 (1): 74–9. doi:10.3109/03009742.2014.927917. PMID 25314295.

- Freyberg, R.H.; et al. (July 1941). "Metabolism, toxicity and manner of action of gold compounds used in the treatment of arthritis. I. Human plasma and synovial fluid concentration and urinary excretion of gold during and following treatment with gold sodium thiomalate, gold sodium thiosulfate, and colloidal gold sulfide". J Clin Invest. 20 (4): 401–412. doi:10.1172/jci101235. PMC 435072. PMID 16694848.

- Lamboley, Claude (December 6, 2010). "Deux rhumatisants au soleil du Midi : Renoir et Dufy" [Two rheumatic in the Midi sun: Renoir and Dufy] (PDF). Académie des Sciences et Lettres de Montpellier (in French). Montpellier. Retrieved July 7, 2015.