Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is the treatment of disease by activating or suppressing the immune system. Immunotherapies designed to elicit or amplify an immune response are classified as activation immunotherapies, while immunotherapies that reduce or suppress are classified as suppression immunotherapies.

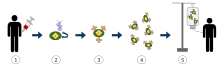

- T-cells (represented by objects labeled as ’t’) are removed from the patient's blood.

- Then in a lab setting the gene that encodes for the specific antigen receptors are incorporated into the T-cells.

- Thus producing the CAR receptors (labeled as c) on the surface of the cells.

- The newly modified T-cells are then further harvested and grown in the lab.

- After a certain time period, the engineered T-cells are infused back into the patient.

| Immunotherapy | |

|---|---|

| MeSH | D007167 |

| OPS-301 code | 8-03 |

In recent years, immunotherapy has become of great interest to researchers, clinicians and pharmaceutical companies, particularly in its promise to treat various forms of cancer.[1][2]

Immunomodulatory regimens often have fewer side effects than existing drugs, including less potential for creating resistance when treating microbial disease.[3]

Cell-based immunotherapies are effective for some cancers. Immune effector cells such as lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer cells (NK Cell), cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), etc., work together to defend the body against cancer by targeting abnormal antigens expressed on the surface of tumor cells.

Therapies such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), interferons, imiquimod and cellular membrane fractions from bacteria are licensed for medical use. Others including IL-2, IL-7, IL-12, various chemokines, synthetic cytosine phosphate-guanosine (CpG) oligodeoxynucleotides and glucans are involved in clinical and preclinical studies.

Immunomodulators

Immunomodulators are the active agents of immunotherapy. They are a diverse array of recombinant, synthetic, and natural preparations.

| Class | Example agents |

|---|---|

| Interleukins | IL-2, IL-7, IL-12 |

| Cytokines | Interferons, G-CSF |

| Chemokines | CCL3, CCL26, CXCL7 |

| Immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs) | thalidomide and its analogues (lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and apremilast) |

| Other | cytosine phosphate-guanosine, oligodeoxynucleotides, glucans |

Activation immunotherapies

Cancer

Cancer immunotherapy attempts to stimulate the immune system to destroy tumors. A variety of strategies are in use or are undergoing research and testing. Randomized controlled studies in different cancers resulting in significant increase in survival and disease free period have been reported[2] and its efficacy is enhanced by 20–30% when cell-based immunotherapy is combined with conventional treatment methods.[2]

One of the oldest forms of cancer immunotherapy is the use of BCG vaccine, which was originally to vaccinate against tuberculosis and later was found to be useful in the treatment of bladder cancer.[4] The use of monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy was first introduced with anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, and since such antibodies activate various components of the immune system, they should be considered as potentially immunomodulatory.

The extraction of G-CSF lymphocytes from the blood and expanding in vitro against a tumour antigen before reinjecting the cells with appropriate stimulatory cytokines. The cells then destroy the tumor cells that express the antigen.

Topical immunotherapy utilizes an immune enhancement cream (imiquimod) which produces interferon, causing the recipient's killer T cells to destroy warts,[5] actinic keratoses, basal cell cancer, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia,[6] squamous cell cancer,[7][8] cutaneous lymphoma,[9] and superficial malignant melanoma.[10]

Injection immunotherapy ("intralesional" or "intratumoral") uses mumps, candida, the HPV vaccine[11][12] or trichophytin antigen injections to treat warts (HPV induced tumors).

Adoptive cell transfer has been tested on lung [13] and other cancers, with greatest success achieved in melanoma.

Dendritic cell-based pump-priming

Dendritic cells can be stimulated to activate a cytotoxic response towards an antigen. Dendritic cells, a type of antigen presenting cell, are harvested from the person needing the immunotherapy. These cells are then either pulsed with an antigen or tumor lysate or transfected with a viral vector, causing them to display the antigen. Upon transfusion into the person, these activated cells present the antigen to the effector lymphocytes (CD4+ helper T cells, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and B cells). This initiates a cytotoxic response against tumor cells expressing the antigen (against which the adaptive response has now been primed). The cancer vaccine Sipuleucel-T is one example of this approach.[14]

T-cell adoptive transfer

Adoptive cell transfer in vitro cultivates autologous, extracted T cells for later transfusion.[15]

Alternatively, Genetically engineered T cells are created by harvesting T cells and then infecting the T cells with a retrovirus that contains a copy of a T cell receptor (TCR) gene that is specialised to recognise tumour antigens. The virus integrates the receptor into the T cells' genome. The cells are expanded non-specifically and/or stimulated. The cells are then reinfused and produce an immune response against the tumour cells.[16] The technique has been tested on refractory stage IV metastatic melanomas[15] and advanced skin cancer[17][18][19]

Whether T cells are genetically engineered or not, before reinfusion, lymphodepletion of the recipient is required to eliminate regulatory T cells as well as unmodified, endogenous lymphocytes that compete with the transferred cells for homeostatic cytokines.[15][20][21][22] Lymphodepletion may be achieved by myeloablative chemotherapy, to which total body irradiation may be added for greater effect.[23] Transferred cells multiplied in vivo and persisted in peripheral blood in many people, sometimes representing levels of 75% of all CD8+ T cells at 6–12 months after infusion.[24] As of 2012, clinical trials for metastatic melanoma were ongoing at multiple sites.[25] Clinical responses to adoptive transfer of T cells were observed in patients with metastatic melanoma resistant to multiple immunotherapies.[26]

Immune enhancement therapy

Autologous immune enhancement therapy use a person's own peripheral blood-derived natural killer cells, cytotoxic T lymphocytes, epithelial cells and other relevant immune cells are expanded in vitro and then reinfused.[27] The therapy has been tested against Hepatitis C,[28][29][30] Chronic fatigue syndrome[31][32] and HHV6 infection.[33]

Suppression immunotherapies

Immune suppression dampens an abnormal immune response in autoimmune diseases or reduces a normal immune response to prevent rejection of transplanted organs or cells.

Immunosuppressive drugs

Immunosuppressive drugs help manage organ transplantation and autoimmune disease. Immune responses depend on lymphocyte proliferation. Cytostatic drugs are immunosuppressive. Glucocorticoids are somewhat more specific inhibitors of lymphocyte activation, whereas inhibitors of immunophilins more specifically target T lymphocyte activation. Immunosuppressive antibodies target steps in the immune response. Other drugs modulate immune responses.

Immune tolerance

The body naturally does not launch an immune system attack on its own tissues. Immune tolerance therapies seek to reset the immune system so that the body stops mistakenly attacking its own organs or cells in autoimmune disease or accepts foreign tissue in organ transplantation.[34] Creating immunity reduces or eliminates the need for lifelong immunosuppression and attendant side effects. It has been tested on transplantations, and type 1 diabetes or other autoimmune disorders.

Allergies

Immunotherapy is used to treat allergies. While allergy treatments (such as antihistamines or corticosteroids) treat allergic symptoms, immunotherapy can reduce sensitivity to allergens, lessening its severity.

Immunotherapy may produce long-term benefits.[35] Immunotherapy is partly effective in some people and ineffective in others, but it offers allergy sufferers a chance to reduce or stop their symptoms.

The therapy is indicated for people who are extremely allergic or who cannot avoid specific allergens. Immunotherapy is generally not indicated for food or medicinal allergies. This therapy is particularly useful for people with allergic rhinitis or asthma.

The first dose contain tiny amounts of the allergen or antigen. Dosages increase over time, as the person becomes desensitized. This technique has been tested on infants to prevent peanut allergies.[36]

Helminthic therapies

Whipworm ova (Trichuris suis) and Hookworm (Necator americanus) have been tested for immunological diseases and allergies. Helminthic therapy has been investigated as a treatment for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis[37] Crohn's,[38][39][40] allergies and asthma.[41] The mechanism of how the helminths modulate the immune response, is unknown. Hypothesized mechanisms include re-polarisation of the Th1 / Th2 response[42] and modulation of dendritic cell function.[43][44] The helminths down regulate the pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokines, Interleukin-12 (IL-12), Interferon-Gamma (IFN-γ) and Tumour Necrosis Factor-Alpha (TNF-ά), while promoting the production of regulatory Th2 cytokines such as IL-10, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13.[42][45]

Co-evolution with helminths has shaped some of the genes associated with Interleukin expression and immunological disorders, such Crohn's, ulcerative colitis and celiac disease. Helminth's relationship to humans as hosts should be classified as mutualistic or symbiotic.

See also

References

- "Immunotherapy | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center". www.mskcc.org. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- Syn NL, Teng MW, Mok TS, Soo RA (December 2017). "De-novo and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint targeting". The Lancet. Oncology. 18 (12): e731–e741. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30607-1. PMID 29208439.

- Masihi KN (July 2001). "Fighting infection using immunomodulatory agents". Expert Opin Biol Ther. 1 (4): 641–53. doi:10.1517/14712598.1.4.641. PMID 11727500.

- Fuge O, Vasdev N, Allchorne P, Green JS (2015). "Immunotherapy for bladder cancer". Research and Reports in Urology. 7: 65–79. doi:10.2147/RRU.S63447. PMC 4427258. PMID 26000263.

- van Seters M, van Beurden M, ten Kate FJ, Beckmann I, Ewing PC, Eijkemans MJ, Kagie MJ, Meijer CJ, Aaronson NK, Kleinjan A, Heijmans-Antonissen C, Zijlstra FJ, Burger MP, Helmerhorst TJ (April 2008). "Treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (14): 1465–73. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072685. PMID 18385498.

- Buck HW, Guth KJ (October 2003). "Treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (primarily low grade) with imiquimod 5% cream". J Low Genit Tract Dis. 7 (4): 290–3. doi:10.1097/00128360-200310000-00011. PMID 17051086.

- Järvinen R, Kaasinen E, Sankila A, Rintala E (August 2009). "Long-term efficacy of maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guérin versus maintenance mitomycin C instillation therapy in frequently recurrent TaT1 tumours without carcinoma in situ: a subgroup analysis of the prospective, randomised FinnBladder I study with a 20-year follow-up". Eur. Urol. 56 (2): 260–5. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2009.04.009. PMID 19395154.

- Davidson HC, Leibowitz MS, Lopez-Albaitero A, Ferris RL (September 2009). "Immunotherapy for head and neck cancer". Oral Oncol. 45 (9): 747–51. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.02.009. PMID 19442565.

- Dani T, Knobler R (2009). "Extracorporeal photoimmunotherapy-photopheresis". Front. Biosci. 14 (14): 4769–77. doi:10.2741/3566. PMID 19273388.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D (June 2009). "Melanoma and immunotherapy". Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 23 (3): 547–64, ix–x. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2009.03.009. PMID 19464602.

- Chuang CM, Monie A, Wu A, Hung CF (2009). "Combination of apigenin treatment with therapeutic HPV DNA vaccination generates enhanced therapeutic anti tumor effects". J. Biomed. Sci. 16 (1): 49. doi:10.1186/1423-0127-16-49. PMC 2705346. PMID 19473507.

- Pawlita M, Gissmann L (April 2009). "[Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: indication for HPV vaccination?]". Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. (in German). 134 Suppl 2: S100–2. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1220219. PMID 19353471.

- Kang N, Zhou J, Zhang T, Wang L, Lu F, Cui Y, Cui L, He W (August 2009). "Adoptive immunotherapy of lung cancer with immobilized anti-TCRgammadelta antibody-expanded human gammadelta T-cells in peripheral blood". Cancer Biol. Ther. 8 (16): 1540–9. doi:10.4161/cbt.8.16.8950. PMID 19471115.

- Di Lorenzo G, Buonerba C, Kantoff PW (September 2011). "Immunotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer". Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 8 (9): 551–61. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.72. PMID 21606971.

- Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP, Yang JC, Morgan RA, Dudley ME (April 2008). "Adoptive cell transfer: A clinical path to effective cancer immunotherapy". Nature Reviews Cancer. 8 (4): 299–308. doi:10.1038/nrc2355. PMC 2553205. PMID 18354418.

- Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Restifo NP, Zheng Z, Nahvi A, de Vries CR, Rogers-Freezer LJ, Mavroukakis SA, Rosenberg SA (October 2006). "Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes". Science. 314 (5796): 126–9. doi:10.1126/science.1129003. PMC 2267026. PMID 16946036.

- Hunder NN, Wallen H, Cao J, Hendricks DW, Reilly JZ, Rodmyre R, Jungbluth A, Gnjatic S, Thompson JA, Yee C (June 2008). "Treatment of metastatic melanoma with autologous CD4+ T cells against NY-ESO-1". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (25): 2698–703. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0800251. PMC 3277288. PMID 18565862.

- "2008 Symposium Program & Speakers". Cancer Research Institute. Archived from the original on 2008-10-15.

- Highfield R (18 June 2008). "Cancer patient recovers after injection of immune cells". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 September 2008.

- Antony PA, Piccirillo CA, Akpinarli A, Finkelstein SE, Speiss PJ, Surman DR, Palmer DC, Chan CC, Klebanoff CA, Overwijk WW, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP (March 2005). "CD8+ T cell immunity against a tumor/self-antigen is augmented by CD4+ T helper cells and hindered by naturally occurring T regulatory cells". Journal of Immunology. 174 (5): 2591–601. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2591. PMC 1403291. PMID 15728465.

- Gattinoni L, Finkelstein SE, Klebanoff CA, Antony PA, Palmer DC, Spiess PJ, Hwang LN, Yu Z, Wrzesinski C, Heimann DM, Surh CD, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP (October 2005). "Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells". J. Exp. Med. 202 (7): 907–12. doi:10.1084/jem.20050732. PMC 1397916. PMID 16203864.

- Dummer W, Niethammer AG, Baccala R, Lawson BR, Wagner N, Reisfeld RA, Theofilopoulos AN (July 2002). "T cell homeostatic proliferation elicits effective antitumor autoimmunity". J. Clin. Invest. 110 (2): 185–92. doi:10.1172/JCI15175. PMC 151053. PMID 12122110.

- Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, Hughes MS, Royal R, Kammula U, Robbins PF, Huang J, Citrin DE, Leitman SF, Wunderlich J, Restifo NP, Thomasian A, Downey SG, Smith FO, Klapper J, Morton K, Laurencot C, White DE, Rosenberg SA (November 2008). "Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens". J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (32): 5233–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449. PMC 2652090. PMID 18809613.

- Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Sherry R, Restifo NP, Hubicki AM, Robinson MR, Raffeld M, Duray P, Seipp CA, Rogers-Freezer L, Morton KE, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Rosenberg SA (October 2002). "Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes". Science. 298 (5594): 850–4. doi:10.1126/science.1076514. PMC 1764179. PMID 12242449.

- Pilon-Thomas S, Kuhn L, Ellwanger S, Janssen W, Royster E, Marzban S, Kudchadkar R, Zager J, Gibney G, Sondak VK, Weber J, Mulé JJ, Sarnaik AA (October 2012). "Efficacy of adoptive cell transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes after lymphopenia induction for metastatic melanoma". J. Immunother. 35 (8): 615–20. doi:10.1097/CJI.0b013e31826e8f5f. PMC 4467830. PMID 22996367.

- Andersen R, Borch TH, Draghi A, Gokuldass A, Rana MA, Pedersen M, Nielsen M, Kongsted P, Kjeldsen JW, Westergaard MC, Radic HD, Chamberlain CA, Holmich LR, Hendel HW, Larsen MS, Met O, Svane IM, Donia M (April 2018). "T cells isolated from patients with checkpoint inhibitor resistant-melanoma are functional and can mediate tumor regression". Ann. Oncol. 29 (7): 1575–1581. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy139. PMID 29688262.

- Manjunath SR, Ramanan G, Dedeepiya VD, Terunuma H, Deng X, Baskar S, Senthilkumar R, Thamaraikannan P, Srinivasan T, Preethy S, Abraham SJ (January 2012). "Autologous immune enhancement therapy in recurrent ovarian cancer with metastases: a case report". Case Rep. Oncol. 5 (1): 114–8. doi:10.1159/000337319. PMC 3364094. PMID 22666198.

- Li Y, Zhang T, Ho C, Orange JS, Douglas SD, Ho WZ (December 2004). "Natural killer cells inhibit hepatitis C virus expression". J. Leukoc. Biol. 76 (6): 1171–9. doi:10.1189/jlb.0604372. PMID 15339939.

- Doskali M, Tanaka Y, Ohira M, Ishiyama K, Tashiro H, Chayama K, Ohdan H (March 2011). "Possibility of adoptive immunotherapy with peripheral blood-derived CD3⁻CD56+ and CD3+CD56+ cells for inducing antihepatocellular carcinoma and antihepatitis C virus activity". J. Immunother. 34 (2): 129–38. doi:10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182048c4e. PMID 21304407.

- Terunuma H, Deng X, Dewan Z, Fujimoto S, Yamamoto N (2008). "Potential role of NK cells in the induction of immune responses: implications for NK cell-based immunotherapy for cancers and viral infections". Int. Rev. Immunol. 27 (3): 93–110. doi:10.1080/08830180801911743. PMID 18437601.

- See DM, Tilles JG (1996). "alpha-Interferon treatment of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome". Immunol. Invest. 25 (1–2): 153–64. doi:10.3109/08820139609059298. PMID 8675231.

- Ojo-Amaize EA, Conley EJ, Peter JB (January 1994). "Decreased natural killer cell activity is associated with severity of chronic fatigue immune dysfunction syndrome". Clin. Infect. Dis. 18 Suppl 1: S157–9. doi:10.1093/clinids/18.Supplement_1.S157. PMID 8148445.

- Kida K, Isozumi R, Ito M (December 2000). "Killing of human Herpes virus 6-infected cells by lymphocytes cultured with interleukin-2 or -12". Pediatr. Int. 42 (6): 631–6. doi:10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01315.x. PMID 11192519.

- Rotrosen D, Matthews JB, Bluestone JA (July 2002). "The immune tolerance network: a new paradigm for developing tolerance-inducing therapies". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 110 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1067/mai.2002.124258. PMID 12110811.

- Durham SR, Walker SM, Varga EM, Jacobson MR, O'Brien F, Noble W, Till SJ, Hamid QA, Nouri-Aria KT (August 1999). "Long-term clinical efficacy of grass-pollen immunotherapy". N. Engl. J. Med. 341 (7): 468–75. doi:10.1056/NEJM199908123410702. PMID 10441602.

- "Clinical Trials Search Results - Stanford University School of Medicine". med.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-03.

- Correale J, Farez M (February 2007). "Association between parasite infection and immune responses in multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 61 (2): 97–108. doi:10.1002/ana.21067. PMID 17230481.

- Croese J, O'neil J, Masson J, Cooke S, Melrose W, Pritchard D, Speare R (January 2006). "A proof of concept study establishing Necator americanus in Crohn's patients and reservoir donors". Gut. 55 (1): 136–7. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.079129. PMC 1856386. PMID 16344586.

- Reddy A, Fried B (January 2009). "An update on the use of helminths to treat Crohn's and other autoimmunune diseases". Parasitol. Res. 104 (2): 217–21. doi:10.1007/s00436-008-1297-5. PMID 19050918.

- Laclotte C, Oussalah A, Rey P, Bensenane M, Pluvinage N, Chevaux JB, Trouilloud I, Serre AA, Boucekkine T, Bigard MA, Peyrin-Biroulet L (December 2008). "[Helminths and inflammatory bowel diseases]". Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. (in French). 32 (12): 1064–74. doi:10.1016/j.gcb.2008.04.030. PMID 18619749.

- Zaccone P, Fehervari Z, Phillips JM, Dunne DW, Cooke A (October 2006). "Parasitic worms and inflammatory diseases". Parasite Immunol. 28 (10): 515–23. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00879.x. PMC 1618732. PMID 16965287.

- Brooker S, Bethony J, Hotez PJ (2004). Human Hookworm Infection in the 21st Century. Advances in Parasitology. 58. pp. 197–288. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(04)58004-1. ISBN 9780120317585. PMC 2268732. PMID 15603764.

- Fujiwara RT, Cançado GG, Freitas PA, Santiago HC, Massara CL, Dos Santos Carvalho O, Corrêa-Oliveira R, Geiger SM, Bethony J (2009). Yazdanbakhsh M (ed.). "Necator americanus infection: a possible cause of altered dendritic cell differentiation and eosinophil profile in chronically infected individuals". PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3 (3): e399. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000399. PMC 2654967. PMID 19308259.

- Carvalho L, Sun J, Kane C, Marshall F, Krawczyk C, Pearce EJ (January 2009). "Review series on helminths, immune modulation and the hygiene hypothesis: mechanisms underlying helminth modulation of dendritic cell function". Immunology. 126 (1): 28–34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03008.x. PMC 2632707. PMID 19120496.

- Fumagalli M, Pozzoli U, Cagliani R, Comi GP, Riva S, Clerici M, Bresolin N, Sironi M (June 2009). "Parasites represent a major selective force for interleukin genes and shape the genetic predisposition to autoimmune conditions". J. Exp. Med. 206 (6): 1395–408. doi:10.1084/jem.20082779. PMC 2715056. PMID 19468064.

- Hong CH, Tang MR, Hsu SH, Yang CH, Tseng CS, Ko YC, et al. (September 2019). "Enhanced early immune response of leptospiral outer membrane protein LipL32 stimulated by narrow band mid-infrared exposure". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology. B, Biology. 198: 111560. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111560. PMID 31336216.

- Chang HY, Li MH, Huang TC, Hsu CL, Tsai SR, Lee SC, et al. (February 2015). "Quantitative proteomics reveals middle infrared radiation-interfered networks in breast cancer cells". Journal of Proteome Research. 14 (2): 1250–62. doi:10.1021/pr5011873. PMID 25556991.

- Nagaya T, Okuyama S, Ogata F, Maruoka Y, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H (May 2019). "Near infrared photoimmunotherapy using a fiber optic diffuser for treating peritoneal gastric cancer dissemination". Gastric Cancer. 22 (3): 463–472. doi:10.1007/s10120-018-0871-5. PMID 30171392.

- Mitsunaga M, Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Rosenblum LT, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H (November 2011). "Cancer cell-selective in vivo near infrared photoimmunotherapy targeting specific membrane molecules". Nature Medicine. 17 (12): 1685–91. doi:10.1038/nm.2554. PMC 3233641. PMID 22057348.

- Sato K, Sato N, Xu B, Nakamura Y, Nagaya T, Choyke PL, et al. (August 2016). "Spatially selective depletion of tumor-associated regulatory T cells with near-infrared photoimmunotherapy". Science Translational Medicine. 8 (352): 352ra110. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6843. PMID 27535621.

- Nagaya T, Nakamura Y, Sato K, Harada T, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H (June 2016). "Improved micro-distribution of antibody-photon absorber conjugates after initial near infrared photoimmunotherapy (NIR-PIT)". Journal of Controlled Release. 232: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.04.003. PMC 4893891. PMID 27059723.

- Zhen Z, Tang W, Wang M, Zhou S, Wang H, Wu Z, et al. (February 2017). "Protein Nanocage Mediated Fibroblast-Activation Protein Targeted Photoimmunotherapy To Enhance Cytotoxic T Cell Infiltration and Tumor Control". Nano Letters. 17 (2): 862–869. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04150. PMID 28027646.