Allergen

An allergen is a type of antigen that produces an abnormally vigorous immune response in which the immune system fights off a perceived threat that would otherwise be harmless to the body. Such reactions are called allergies.

In technical terms, an allergen is an antigen that is capable of stimulating a type-I hypersensitivity reaction in atopic individuals through Immunoglobulin E (IgE) responses.[1] Most humans mount significant Immunoglobulin E responses only as a defense against parasitic infections. However, some individuals may respond to many common environmental antigens. This hereditary predisposition is called atopy. In atopic individuals, non-parasitic antigens stimulate inappropriate IgE production, leading to type I hypersensitivity.

Sensitivities vary widely from one person (or from one animal) to another. A very broad range of substances can be allergens to sensitive individuals.

Types of allergens

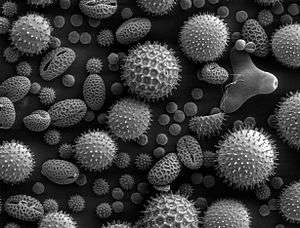

Allergens can be found in a variety of sources, such as dust mite excretion, pollen, pet dander, or even royal jelly.[2] Food allergies are not as common as food sensitivity, but some foods such as peanuts (a legume), nuts, seafood and shellfish are the cause of serious allergies in many people.

Officially, the United States Food and Drug Administration does recognize eight foods as being common for allergic reactions in a large segment of the sensitive population. These include peanuts, tree nuts, eggs, milk, shellfish, fish, wheat and their derivatives, and soy and their derivatives, as well as sulfites (chemical-based, often found in flavors and colors in foods) at 10ppm and over. See the FDA website for complete details. Other countries, in view of the differences in the genetic profiles of their citizens and different levels of exposure to specific foods due to different dietary habits, the "official" allergen list will change. Canada recognizes all eight of the allergens recognized by the US, and also recognizes sesame seeds,[3] and mustard.[4] The European Union additionally recognizes other gluten-containing cereals as well as celery and lupin.

Another allergen is urushiol, a resin produced by poison ivy and poison oak, which causes the skin rash condition known as urushiol-induced contact dermatitis by changing a skin cell's configuration so that it is no longer recognized by the immune system as part of the body. Various trees and wood products such as paper, cardboard, MDF etc. can also cause mild to severe allergy symptoms through touch or inhalation of sawdust such as asthma and skin rash.[5]

An allergic reaction can be caused by any form of direct contact with the allergen—consuming food or drink one is sensitive to (ingestion), breathing in pollen, perfume or pet dander (inhalation), or brushing a body part against an allergy-causing plant (direct contact). Other common causes of serious allergy are wasp,[6] fire ant [7] and bee stings,[8] penicillin,[9] and latex. An extremely serious form of an allergic reaction is called anaphylaxis. One form of treatment is the administration of sterile epinephrine to the person experiencing anaphylaxis, which suppresses the body's overreaction to the allergen, and allows for the patient to be transported to a medical facility.

Common allergens

.jpg)

In addition to foreign proteins found in foreign serum (from blood transfusions) and vaccines, common allergens include:

- Animal products

- Fel d 1 (Allergy to cats)

- fur and dander

- cockroach calyx

- wool

- dust mite excretion

- Drugs

- penicillin

- sulfonamides

- salicylates (also found naturally in numerous fruits)

- Foods

- Insect stings

- bee sting venom

- wasp sting venom

- mosquito stings

- Mold spores

- Top 5 allergens discovered in patch tests in 2005–06:

- nickel sulfate (19.0%)

- Balsam of Peru (11.9%)

- fragrance mix I (11.5%)

- quaternium-15 (10.3%), and

- neomycin (10.0%).[11]

- Metals

- nickel

- chromium

- Other

- latex

- wood

- Plant pollens (hay fever)

- grass — ryegrass, timothy-grass

- weeds — ragweed, plantago, nettle, Artemisia vulgaris, Chenopodium album, sorrel

- trees — birch, alder, hazel, hornbeam, Aesculus, willow, poplar, Platanus, Tilia, Olea, Ashe juniper, Alstonia scholaris

Seasonal allergy

Seasonal allergy symptoms are commonly experienced during specific parts of the year, usually during spring, summer or fall when certain trees or grasses pollinate. This depends on the kind of tree or grass. For instance, some trees such as oak, elm, and maple pollinate in the spring, while grasses such as Bermuda, timothy and orchard pollinate in the summer.

Grass allergy is generally linked to hay fever because their symptoms and causes are somehow similar to each other. Symptoms include rhinitis, which causes sneezing and a runny nose, as well as allergic conjunctivitis, which includes watering and itchy eyes.[12] Also an initial tickle on the roof of the mouth or in the back of the throat may be experienced.

Also, depending on the season, the symptoms may be more severe and people may experience coughing, wheezing, and irritability. A few people even become depressed, lose their appetite, or have problems sleeping. Moreover, since the sinuses may also become congested, some people experience headaches.[13]

If both parents suffered from allergies in the past, there is a 66% chance for the individual to suffer from seasonal allergies, and the risk lowers to 60% if just one parent had suffered from allergies. The immune system also has strong influence on seasonal allergies, since it reacts differently to diverse allergens like pollen. When an allergen enters the body of an individual that is predisposed to allergies, it triggers an immune reaction and the production of antibodies. These allergen antibodies migrate to mast cells lining the nose, eyes and lungs. When an allergen drifts into the nose more than once, mast cells release a slew of chemicals or histamines that irritate and inflame the moist membranes lining the nose and produce the symptoms of an allergic reaction: scratchy throat, itching, sneezing and watery eyes. Some symptoms that differentiate allergies from a cold include:[14]

- No fever.

- Mucous secretions are runny and clear.

- Sneezes occurring in rapid and several sequences.

- Itchy throat, ears and nose.

- These symptoms usually last longer than 7–10 days.

Among seasonal allergies, there are some allergens that fuse together and produce a new type of allergy. For instance, grass pollen allergens cross-react with food allergy proteins in vegetables such as onion, lettuce, carrots, celery and corn. Besides, the cousins of birch pollen allergens, like apples, grapes, peaches, celery and apricots, produce severe itching in the ears and throat. The cypress pollen allergy brings a cross reactivity between diverse species like olive, privet, ash and Russian olive tree pollen allergens. In some rural areas there is another form of seasonal grass allergy, combining airborne particles of pollen mixed with mold.[15] Recent research has suggested that humans might develop allergies as a defense to fight off parasites. According to Yale University Immunologist Dr Ruslan Medzhitov, protease allergens cleave the same sensor proteins that evolved to detect proteases produced by the parasitic worms.[16] Additionally, a new report on seasonal allergies called “Extreme allergies and Global Warming”, have found that many allergy triggers are worsening due to climate change. 16 states in the United States were named as “Allergen Hotspots” for large increases in allergenic tree pollen if global warming pollution keeps increasing. Therefore, researchers on this report claimed that global warming is bad news for millions of asthmatics in the United States whose asthma attacks are triggered by seasonal allergies.[17] Indeed, seasonal allergies are one of the main triggers for asthma, along with colds or flu, cigarette smoke and exercise. In Canada, for example, up to 75% of asthmatics also have seasonal allergies.[18]

Seasonal allergy diagnosis

Based on the symptoms seen on the patient, the answers given in terms of symptom evaluation and a physical exam, doctors can make a diagnosis to identify if the patient has a seasonal allergy. After performing the diagnosis, the doctor is able to tell the main cause of the allergic reaction and recommend the treatment to follow. 2 tests have to be done in order to determine the cause: a blood test and a skin test. Allergists do skin tests in one of two ways: either dropping some purified liquid of the allergen onto the skin and pricking the area with a small needle; or injecting a small amount of allergen under the skin.[19]

Alternative tools are available to identify seasonal allergies, such as laboratory tests, imaging tests and nasal endoscopy. In the laboratory tests, the doctor will take a nasal smear and it will be examined microscopically for factors that may indicate a cause: increased numbers of eosinophils (white blood cells), which indicates an allergic condition. If there is a high count of eosinophils, an allergic condition might be present.

Another laboratory test is the blood test for IgE (immunoglobulin production), such as the radioallergosorbent test (RAST) or the more recent enzyme allergosorbent tests (EAST), implemented to detect high levels of allergen-specific IgE in response to particular allergens. Although blood tests are less accurate than the skin tests, they can be performed on patients unable to undergo skin testing. Imaging tests can be useful to detect sinusitis in people suffering from chronic rhinitis, and they can work when other test results are ambiguous. There is also nasal endoscopy, wherein a tube is inserted through the nose with a small camera to view the passageways and examine any irregularities in the nose structure. Endoscopy can be used for some cases of chronic or unresponsive seasonal rhinitis.[20]

Fungal allergens

In 1952 basidiospores were described as being possible airborne allergens[21] and were linked to asthma in 1969.[22] Basidiospores are the dominant airborne fungal allergens. Fungal allergies are associated with seasonal asthma.[23][24] They are considered to be a major source of airborne allergens.[25] The basidospore family include mushrooms, rusts, smuts, brackets, and puffballs. The airborne spores from mushrooms reach levels comparable to those of mold and pollens. The levels of mushroom respiratory allergy are as high as 30 percent of those with allergic disorder, but it is believed to be less than 1 percent of food allergies.[26][27] Heavy rainfall (which increases fungal spore release) is associated with increased hospital admissions of children with asthma.[28] A study in New Zealand found that 22 percent of patients with respiratory allergic disorders tested positive for basidiospores allergies.[29] Mushroom spore allergies can cause either immediate allergic symptomatology or delayed allergic reactions. Those with asthma are more likely to have immediate allergic reactions and those with allergic rhinitis are more likely to have delayed allergic responses.[30] A study found that 27 percent of patients were allergic to basidiomycete mycelia extracts and 32 percent were allergic to basidiospore extracts, thus demonstrating the high incidence of fungal sensitisation in individuals with suspected allergies.[31] It has been found that of basidiomycete cap, mycelia, and spore extracts that spore extracts are the most reliable extract for diagnosing basidiomycete allergy.[32][33]

In Canada, 8% of children attending allergy clinics were found to be allergic to Ganoderma, a basidiospore.[34] Pleurotus ostreatus,[35] cladosporium,[36] and Calvatia cyathiformis are significant airborne spores.[25] Other significant fungal allergens include aspergillus and alternaria-penicillin families.[37] In India Fomes pectinatus is a predominant air-borne allergen affecting up to 22 percent of patients with respiratory allergies.[38] Some fungal air-borne allergens such as Coprinus comatus are associated with worsening of eczematous skin lesions.[39] Children who are born during autumn months (during fungal spore season) are more likely to develop asthmatic symptoms later in life.[40]

Treatment

Treatment includes over-the-counter medications, antihistamines, nasal decongestants, allergy shots, and alternative medicine. In the case of nasal symptoms, antihistamines are normally the first option. They may be taken together with pseudoephedrine to help relieve a stuffy nose and they can stop the itching and sneezing. Some over-the-counter options are Benadryl and Tavist. However, these antihistamines may cause extreme drowsiness, therefore, people are advised to not operate heavy machinery or drive while taking this kind of medication. Other side effects include dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, difficulty with urination, confusion, and light-headedness.[41] There is also a newer second generation of antihistamines that are generally classified as the "non-sedating antihistamines" or anti-drowsy, which include cetirizine, loratadine, and fexofenadine.[42]

An example of nasal decongestants is pseudoephedrine and its side-effects include insomnia, restlessness, and difficulty urinating. Some other nasal sprays are available by prescription, including Azelastine and Ipratropium. Some of their side-effects include drowsiness. For eye symptoms, it is important to first bath the eyes with plain eyewashes to reduce the irritation. People should not wear contact lenses during episodes of conjunctivitis.

Allergen immunotherapy treatment involves administering doses of allergens to accustom the body to induce specific long-term tolerance.[43] Allergy immunotherapy can be administered orally (as sublingual tablets or sublingual drops), or by injections under the skin (subcutaneous). Immunotherapy contains a small amount of the substance that triggers the allergic reactions.[44]

See also

|

|

References

- Goldsby, Richard A.; et al. Immunology (5th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman.

- Rosmilah, M; et al. (December 2008). "Characterization of major allergens of royal jelly Apis mellifera". Trop Biomed. 25 (3): 243–51. PMID 19287364.

- "Health Canada: Food Allergies". 26 July 2004. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- "CFIA: Revised Labelling Regulations for Food Allergens, Gluten Sources and Sulphites (Amendments to the Food and Drug Regulations)". Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- "Wood Allergies and Toxicity". The Wood Database. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Aparecido dos Santos-Pinto, José Roberto; Delazari dos Santos, Lucilene; Arcuri, Helen Andrade; Ribeiro da Silva Menegasso, Anally; Pêgo, Paloma Napoleão; Santos, Keity Souza; Castro, Fábio Morato; Kalil, Jorge Elias; De-Simone, Salvatore Giovanni (January 2015). "B-cell linear epitopes mapping of antigen-5 allergen from Polybia paulista wasp venom". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 135 (1): 264–267.e8. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.006.

- Zamith-Miranda, Daniel; Fox, Eduardo G. P.; Monteiro, Ana Paula; Gama, Diogo; Poublan, Luiz E.; de Araujo, Almair Ferreira; Araujo, Maria F. C.; Atella, Georgia C.; Machado, Ednildo A. (December 2018). "The allergic response mediated by fire ant venom proteins". Scientific Reports. 8 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-018-32327-z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6158280.

- Lima, P. R. de; Brochetto-Braga, M. R. (2003). "Hymenoptera venom review focusing on Apis mellifera". Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases. 9 (2). doi:10.1590/S1678-91992003000200002. ISSN 1678-9199.

- "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- Bublin M; Radauer C; Wilson IBH; Kraft D; Scheiner O; Breiteneder H; Hoffmann-Sommergruber K (2003). "Cross-reactive N-glycans of Api g 5, a high molecular weight glycoprotein allergen from celery, are required for immunoglobulin E binding and activation of effector cells from allergic patients". FASEB Journal. 17 (12): 1697–9. doi:10.1096/fj.02-0872fje. PMID 12958180. Archived from the original on 4 January 2007.

- Zug KA, Warshaw EM, Fowler JF Jr, Maibach HI, Belsito DL, Pratt MD, Sasseville D, Storrs FJ, Taylor JS, Mathias CG, Deleo VA, Rietschel RL, Marks J. Patch-test results of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2005–2006. Dermatitis. 2009 May–Jun;20(3):149-60.

- "Seasonal Allergy — What to Know". Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "Seasonal Allergies". Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- Seasonal allergies: Something to sneeze at Archived 2 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine CBS News. Retrieved on 31 August 2010

- Seasonal Allergies: What to know Archived 14 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine Seasonal Allergy. Retrieved on 31 August 2010

- Parasites behind seasonal allergies Archived 8 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine ABC Science. Retrieved on 31 August 2010

- Weinmann, Aileo (14 April 2010) Seasonal allergies getting worse from Climate Change Archived 6 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine National Wildlife Federation. Media Center. Retrieved on 31 August 2010

- Asthma and Allergies: The Symptoms Archived 17 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Asthma & Allergies. Retrieved on 31 August 2010

- Seasonal Allergies Archived 16 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine Kids Health. Retrieved on 31 August 2010

- Allergic Rhinitis Archived 4 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine New York Times Health Guide. Retrieved on 31 August 2010

- Gregory, PH.; Hirst, JM. (September 1952). "Possible role of basidiospores as air-borne allergens". Nature. 170 (4323): 414. doi:10.1038/170414a0. PMID 12993181.

- Herxheimer, H.; Hyde, HA.; Williams, DA. (July 1969). "Allergic asthma caused by basidiospores". Lancet. 2 (7612): 131–3. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(69)92441-6. PMID 4183245.

- Hasnain, SM.; Wilson, JD.; Newhook, FJ. (May 1985). "Fungal allergy and respiratory disease". N Z Med J. 98 (778): 342–6. PMID 3858721.

- Levetin, E. (April 1989). "Basidiospore identification". Ann Allergy. 62 (4): 306–10. PMID 2705657.

- Horner, WE.; Lopez, M.; Salvaggio, JE.; Lehrer, SB. (1991). "Basidiomycete allergy: identification and characterization of an important allergen from Calvatia cyathiformis". Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 94 (1–4): 359–361. doi:10.1159/000235403. PMID 1937899.

- Sprenger, JD.; Altman, LC.; O'Neil, CE.; Ayars, GH.; Butcher, BT.; Lehrer, SB. (December 1988). "Prevalence of basidiospore allergy in the Pacific Northwest". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 82 (6): 1076–1080. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(88)90146-7. PMID 3204251.

- Koivikko, A.; Savolainen, J. (January 1988). "Mushroom allergy". Allergy. 43 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1988.tb02037.x. PMID 3278649.

- Khot, A.; Burn, R.; Evans, N.; Lenney, W.; Storr, J. (July 1988). "Biometeorological triggers in childhood asthma". Clin Allergy. 18 (4): 351–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.1988.tb02882.x. PMID 3416418.

- Hasnain, SM.; Wilson, JD.; Newhook, FJ.; Segedin, BP. (May 1985). "Allergy to basidiospores: immunologic studies". N Z Med J. 98 (779): 393–6. PMID 3857522.

- Santilli, J.; Rockwell, WJ.; Collins, RP. (September 1985). "The significance of the spores of the Basidiomycetes (mushrooms and their allies) in bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis". Ann Allergy. 55 (3): 469–71. PMID 4037433.

- Lehrer, SB.; Lopez, M.; Butcher, BT.; Olson, J.; Reed, M.; Salvaggio, JE. (September 1986). "Basidiomycete mycelia and spore-allergen extracts: skin test reactivity in adults with symptoms of respiratory allergy". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 78 (3 Pt 1): 478–485. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(86)90036-9. PMID 3760405.

- Weissman, DN.; Halmepuro, L.; Salvaggio, JE.; Lehrer, SB. (1987). "Antigenic/allergenic analysis of basidiomycete cap, mycelia, and spore extracts". Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 84 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1159/000234398. PMID 3623711.

- Liengswangwong, V.; Salvaggio, JE.; Lyon, FL.; Lehrer, SB. (May 1987). "Basidiospore allergens: determination of optimal extraction methods". Clin Allergy. 17 (3): 191–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.1987.tb02003.x. PMID 3608137.

- Tarlo, SM.; Bell, B.; Srinivasan, J.; Dolovich, J.; Hargreave, FE. (July 1979). "Human sensitization to Ganoderma antigen". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 64 (1): 43–49. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(79)90082-4. PMID 447950.

- Lopez, M.; Butcher, BT.; Salvaggio, JE.; Olson, JA.; Reed, MA.; McCants, ML.; Lehrer, SB. (1985). "Basidiomycete allergy: what is the best source of antigen?". Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 77 (1–2): 169–170. doi:10.1159/000233775. PMID 4008070.

- Stephen, E.; Raftery, AE.; Dowding, P. (August 1990). "Forecasting spore concentrations: a time series approach". Int J Biometeorol. 34 (2): 87–89. doi:10.1007/BF01093452. PMID 2228299.

- Dhillon, M. (May 1991). "Current status of mold immunotherapy". Ann Allergy. 66 (5): 385–92. PMID 2035901.

- Gupta, SK.; Pereira, BM.; Singh, AB. (March 1999). "Fomes pectinatis: an aeroallergen in India". Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 17 (1): 1–7. PMID 10403002.

- Fischer, B.; Yawalkar, N.; Brander, KA.; Pichler, WJ.; Helbling, A. (October 1999). "Coprinus comatus (shaggy cap) is a potential source of aeroallergen that may provoke atopic dermatitis". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 104 (4 Pt 1): 836–841. doi:10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70295-2. PMID 10518829.

- Harley, KG.; Macher, JM.; Lipsett, M.; Duramad, P.; Holland, NT.; Prager, SS.; Ferber, J.; Bradman, A.; et al. (April 2009). "Fungi and pollen exposure in the first months of life and risk of early childhood wheezing". Thorax. 64 (4): 353–8. doi:10.1136/thx.2007.090241. PMC 3882001. PMID 19240083.

- "Seasonal Allergies". Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "Non-Sedating or Anti-Drowsy Antihistamine Tablets". Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- Van Overtvelt L. et al. Immune mechanisms of allergen-specific sublingual immunotherapy. Revue française d’allergologie et d’immunologie clinique. 2006; 46: 713–720.

- "Allergy shots". Archived from the original on 22 April 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.