Endrin

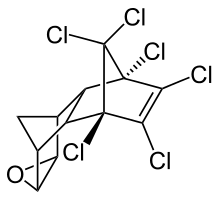

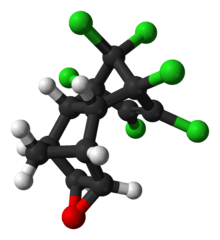

Endrin is an organochloride with the chemical formula C12H8Cl6O that was first produced in 1950 by Shell and Velsicol Chemical Corporation. It was primarily used as an insecticide, as well as a rodenticide and piscicide. It is a colourless, odorless solid, although commercial samples are often off-white. Endrin was manufactured as an emulsifiable solution known commercially as Endrex.[5] The compound became infamous as a persistent organic pollutant and for this reason it is banned in many countries.[6]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(1R,2S,3R,6S,7R,8S,9S,11R)-3,4,5,6,13,13-Hexachloro-10-oxapentacyclo[6.3.1.13,6.02,7.09,11]tridec-4-ene | |

| Other names

Mendrin, Compound 269, (1aR,2S,2aS,3S,6R,6aR,7R,7aS)-3,4,5,6,9,9-hexachloro-1a,2,2a,3,6,6a,7,7a-octahydro-2,7:3,6-dimethanonaphtho[2,3-b]oxirene, 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-6,7-epoxy-1,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydro-1,4-endo,endo-5,8-dimethanonaphthalene | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.705 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2761 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C12H8Cl6O |

| Molar mass | 380.907 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless to tan crystalline solid |

| Density | 1.77 g/cm3 [1] |

| Melting point | 200 °C (392 °F; 473 K) (decomposes) |

Solubility in water |

0.23 mg/L[2] |

| Vapor pressure | 2.6 x 10-5 Pa[1] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |    |

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements |

H301, H310, H351, H372, H400, H410 |

GHS precautionary statements |

P201, P202, P260, P262, P264, P270, P273, P280, P281, P301+310, P302+350, P308+313, P310, P314, P321, P322, P330, P361, P363, P391, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | noncombustible [3] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

3 mg/kg (oral, monkey) 16 mg/kg (oral, guinea pig) 10 mg/kg (oral, hamster) 3 mg/kg (oral, rat) 7 mg/kg (oral, rabbit) 1.4 mg/kg (oral, mouse)[4] |

LDLo (lowest published) |

5 mg/kg (cat, oral)[4] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 0.1 mg/m3 [skin][3] |

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 0.1 mg/m3 [skin][3] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

2 mg/m3[3] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

In the environment endrin exists as either endrin aldehyde or endrin ketone and can be found mainly in bottom sediments of bodies of water.[7][8] Exposure to endrin can occur by inhalation, ingestion of substances containing the compound, or skin contact.[7] Upon entering the body, it can be stored in body fats and can act as a neurotoxin on the central nervous system, which can cause convulsions, seizures, or even death.[9]

Although endrin is not currently classified as a mutagen,[5] nor as a human carcinogen, it is still a toxic chemical in other ways with detrimental effects.[10] Due to these toxic effects, the manufacturers cancelled all use of endrin in the United States by 1991. Food import concerns have been raised because some countries may have still been using endrin as a pesticide.[7]

History

J. Hyman & Company first developed endrin in 1950. Shell International was licensed in the United States and in the Netherlands to produce it. Velsicol was the other producer in the Netherlands. Endrin was used globally until the early 1970s. Due to its toxicity, it was banned or severely restricted in many countries. In 1982, Shell discontinued its manufacturing.[5]

In 1962, an estimated 2.3-4.5 million kilograms of endrin were sold by Shell in the USA. In 1970, Japan imported 72,000 kilograms of endrin. From 1963 until 1972, Bali used 171 to 10,700 kilograms of endrin annually for the production of rice paddies until endrin use was discontinued in 1972.[5] Taiwan reported to show higher levels of organochlorine pesticides including endrin in soil samples of paddy fields, compared to other Asian countries such as Thailand and Vietnam. During the 1950s-1970s over two million kilograms of organochlorine pesticides were estimated of having been be released into the environment per year. Endrin was banned in the United States on October 10, 1984.[8] Taiwan banned endrin's use as a pesticide in 1971 and regulated it as a toxic chemical in 1989.[11]

In May 2004, the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants came into effect and listed endrin as one of the 12 initial persistent organic pollutants (POPs) that have been causing adverse effects on humans and the environment. The convention requires the participating parties to take measures to eliminate or restrict the production of POPs.[12]

Production

The synthesis of endrin begins with the condensation of hexachlorocyclopentadiene with vinyl chloride. The product is then dehydrochlorinated. Following reaction with cyclopentadiene, isodrin is formed. Epoxide formation by adding either peracetic acid or perbenzoic acid to the isodrin is the final step in synthesizing endrin.[5]

Endrin is a stereoisomer of dieldrin[13] with comparable properties, though endrin degrades more easily[8]

Use

Endrin was formulated as emulsifiable concentrates (ECs), wettable powders (WPs), granules, field strength dusts (FSDs), and pastes. The product could then be applied by aircraft or by handheld sprayers in its various formulations.[14]

Endrin has been used primarily as an agricultural insecticide on tobacco, apple trees, cotton, sugar cane, rice, cereal, and grains.[15] It is effective against a variety of species, including cotton bollworms, corn borers, cut worms and grass hoppers.[16] In addition, endrin has been employed as a rodenticide and avicide.[7] In Malaysia, fish farms used a solution of endrin as a piscicide to rid mine pools and fish ponds of all fish prior to restocking.[17]

A study conducted from 1981 to 1983 in the US aimed to determine endrin's effects on non-target organisms when applied as a rodenticide in orchards. Most wildlife in and around the orchard was found to have endrin exposure, with endrin toxicity accounting for more than 24% of bird deaths recorded.[18] Endrin was eventually banned in the US on October 10, 1984.[8]

Health effects

Exposure and metabolism

Exposure to endrin can occur by inhalation, ingestion of substances containing the compound, or by skin contact. In addition to inhalation and skin contact, infants can be exposed by ingesting the breast milk of an exposed woman. In utero, fetuses are exposed by way of the placenta if the mother has been exposed.[13][19]

Upon entering the body, endrin metabolizes into anti-12-hydroxyendrin and other metabolites, which can be expelled in the urine and feces. Both anti-12-hydroxyendrin and its metabolite, 12-ketoendrin, are likely responsible for the toxicity of endrin.[7] The rapid metabolism of endrin into these metabolites makes detection of endrin itself difficult unless exposure is very high.[13]

Neurological effects

Symptoms of endrin poisoning include headache, dizziness, nervousness, confusion, nausea, vomiting, and convulsions.[7] Acute endrin poisoning in humans affects primarily the central nervous system. There, it can act as a neurotoxin that blocks the activity of inhibitory neurotransmitters.[13] In cases of acute exposure, this may result in seizures, or even death. Because endrin can be stored in body fats, acute endrin poisoning can lead to recurrent seizures when stressors induce the release of endrin back into the body, even months after the initial exposure is terminated.[9]

People occupationally exposed to endrin may experience abnormal EEG readings even if they exhibit none of the clinical symptoms, possibly due to injury to the brain stem. These readings show bilateral synchronous theta waves with synchronous spike-and-wave complexes. EEG readings can take up to one month to return to normal.[7]

Developmental effects

Though endrin exposure has not been found to adversely affect fertility in mammals, an increase in fetal mortality has been observed in mice, rats, and mallard ducks. In those animals that have survived gestation, developmental abnormalities have been observed, particularly in rodents whose mothers were exposed to endrin early in pregnancy. In hamsters, the number of cases of fused ribs, cleft palate, open eyes, webbed feet, and meningoencephaloceles have increased. Along with open eyes and cleft palate, mice have developed with fused ribs and exencephaly.[7] Skeletal abnormalities in rodents have also been reported.[13]

Other effects

Higher doses of endrin have been found to cause the following in rodents: renal tubular necrosis; inflammation of the liver, fatty liver, and liver necrosis; possible kidney degradation;[13] and a decrease in body weight and body weight gain.[7]

Endrin is very toxic to aquatic organisms, namely fish, aquatic invertebrates, and phytoplankton.[20] It was found to remain in the tissues of infected fish for up to one month.[17]

1984 poisoning outbreak in Pakistan

From July 14 to September 26, 1984, an outbreak of endrin poisoning occurred in 21 villages in and around Talagang, a subdistrict of the Punjab province of Pakistan. Eighty percent of the 194 known cases were children under the age of 15. Poisoned individuals had seizures along with vomiting, pulmonary congestion, and hypoxia, leaving 19 people dead. Some individuals had low grade fevers (37.8 °C/100 °F, axillary) following seizures. The more seriously affected had less vomiting, but higher temperatures than people who were less affected. Most patients could be controlled in under two hours using diazepam, phenobarbital, and atropine, though the more seriously affected patients required general anesthesia. Recovery took up to two days. Following treatment, patients reported not remembering their seizures. The outbreak affected both men and women equally.[21]

Based on the demographics of the affected individuals and their area of residence, the outbreak was likely caused by endrin contamination of food.[22] As members of these villages rarely had contact with one another, investigators determined that contaminated sugar shipped to the villages was the most probable cause, though no credible evidence was found to support this. Around this time, endrin was being used by cotton and sugar cane farmers in the Punjab region. A number of truck drivers stated that they had used the same trucks to deliver endrin to farmers and to pick up crops for Talagang, possibly leading to contamination.[21]

Environmental behavior

Insecticides like dieldrin and endrin have been shown to persist for decades in the environment.[23] A definitive detection of the residues was not possible until 1971 when mass spectrometer started being used as a detector in gas chromatography.[24] Detection of these chemicals in the environment has been reported across the world up to 2005,[23] even though the frequency of reported cases are low due to its relatively small-scale use and very low concentrations.[24]

Endrin regularly enters the environment when applied to crops or when rain washes it off. It has been found in water, sediments, atmospheric air and biotic environment, even after uses have been stopped.[25] Organochlorine pesticides strongly resist degradation, are poorly soluble in water but highly soluble in lipids, which is called lipophilic.[24] This leads to bioaccumulation in fatty tissues of organisms, mainly those dwelling in water. A high bioconcentration factor of 1335-10,000 has been reported in fish.[26] Endrin binds very strongly to organic matter in soil and aquatic sediments due to their high adsorption coefficient,[24] making it less likely to leach into groundwater, even though contaminated groundwater samples have been found. In 2009, EPA released data indicating that the endrin in soil could last up to 14 years or more.[26] The extent of endrin's persistence depends highly on local conditions. For example, high temperature (230 °C) or intense sunlight leads to more rapid breakdown of endrin into endrin ketone and endrin aldehyde, however, this breakdown is less than 5%.[7]

Removal from the environment

In the United States, endrin was mainly disposed in land until U.S. federal regulations were applied in 1987 on land disposal of wastes containing endrin.[7] Primary methods of endrin disappearance from soil are volatilization and photodecomposition.[27] Under ultraviolet light, endrin forms δ-ketoendrin and International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) claims that in intense summer sun, about 50% of endrin is isomerized to δ-ketoendrin in 7 days.[27] In anaerobic conditions microbial degradation by fungi and bacteria takes place to form the same major end product.[14]

Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB) lists reductive dechlorination and incineration for field disposal of small quantities of endrin. In reductive dechlorination, endrin's chlorine atoms were completely replaced with hydrogen atoms, which is suspected to be more environmentally acceptable.[28] Even though endrin binds very strongly to soil, phytoremediation has been proposed by group of Japanese scientists using crops in the family Cucurbitaceae. As of 2009, exact mechanisms behind the plant uptake of endrin have not been understood. Research in uptake mechanisms and factors that influence the uptake is needed for practical application.[23]

Regulation

United States

In the United States, endrin has been regulated by the EPA. It set a freshwater acute criterion of 0.086 µg/L and a chronic criterion of 0.036 µg/L. In saltwater, the numbers are acute 0.037 and chronic 0.0023 µg/L.[20] The human health contaminate criterion for water plus organism is 0.059 µg/L.[29] The drinking water limit (maximum contaminant level) is set to 2 ppb.[30] Use of endrin in fisheries has been advised against due to the zero tolerance of endrin levels in food products.[17] For occupational exposures to endrin, OSHA and NIOSH have set exposure limits at 0.1 mg/m3.[3]

International organizations

The WHO lists Endrin as an obsolete pesticide in its 'Classification of Pesticides by Hazard' and did not assign any hazard class per the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals.[31]

Taiwan

Taiwan is not a party to the Stockholm Convention as of 2015, but has drafted its own "National Implementation Plan of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants" which was approved by the Executive Yuan on April 2008.[11] The Central Competent Authorities of Taiwan sets the limit of 20 mg/kg for soil pollution control. For marine environment quality, standards of 0.002 mg/L has been set. For occupational exposures to endrin, warning has been given that the contact with skin, eyes, and mucous membranes can contribute to the overall exposure.[11]

See also

- Aldrin

- Dieldrin

- Endocrine disruptors

- Pesticide formulation

References

- "Endrin". Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Endrin (PDS)". IPCS. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0252". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Endrin". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). 4 December 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- van Esch, G. T.; van Heemstra-Lequin, E. A. H. (1992). "Environmental Health Criteria 130: Endrin". International Programme on Chemical Safety. World Health Organization. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)". Commonwealth of Australia: Department of the Environment. 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Toxicological Profile for Endrin" (PDF). Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. United States Department of Health and Human Services. August 1996. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Berry, Walter (August 2003). "Procedures for the Derivation of Equilibrium Partitioning Sediment Benchmarks (ESBs) for the Protection of Benthic Organisms: Endrin" (PDF). EPA: Office of Research and Development.

- "Some Acute and Chronic Effects of Endrin on the Brain" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration: Office of Aviation Medicine. July 1970. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Endrin (CASRN 72-20-8)". Integrated Risk Information System. United States Environmental Protection Agency. September 1988. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Tsai, Wen-Tien (12 October 2010). "Current Status and Regulatory Aspects of Pesticides Considered to be Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in Taiwan". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 7 (10): 3615–3627. doi:10.3390/ijerph7103615. PMC 2996183. PMID 21139852.

- "History of the negotiations of the Stockholm Convention". Stockholm Convention. Stockholm Convention. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Organochlorine Pesticides Overview: Endrin". CDC - National Biomonitoring Program. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. December 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Endrin: Health and Safety Guide No. 60". International Programme on Chemical Health. World Health Organization. 1991. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Basic Information about Endrin in Drinking Water". United States Environmental Protection Agency. February 9, 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Data Sheets on Pesticides No. 1: Endrin". International Programme on Chemical Safety. World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization. January 1975. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Integrated Management Techniques to Control Nonnative Fishes" (PDF). Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center. United States Geological Survey. December 2003. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Blus, L.J.; Henny, C.J.; Grove, R.A. (January 1989). "Rise and fall of endrin usage in Washington State fruit orchards: Effects on wildlife". Environmental Pollution. 60 (3–4): 331–349. doi:10.1016/0269-7491(89)90113-9.

- "Healthy Milk, Healthy Baby - Chemical Pollution and a Mother's Milk". National Resources Defense Council. 25 March 2005. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Endrin" (PDF). EPA Water. United States Environmental Protection Agency. October 1980. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "International Notes Acute Convulsions Associated with Endrin Poisoning -- Pakistan". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Center for Disease Control. 14 December 1984. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Jabbar, Abdul (October 1992). "PESTICIDE POISONING IN HUMANS" (PDF). Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Matsumoto, Emiko; Kawanaka, Youhei; Yun, Sun-Ja; Oyaizu, Hiroshi (4 July 2009). "Bioremediation of the organochlorine pesticides, dieldrin and endrin, and their occurrence in the environment". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 84 (2): 205–216. doi:10.1007/s00253-009-2094-5. PMID 19578846.

- Zitko, Vladimir (2003). Persistent Organic Pollutants (PDF). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. pp. 47–90. ISBN 978-3-540-43728-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Chopra, A. K.; Sharma, Mukesh Kumar; Chamoli, Shikha (February 2011). "Bioaccumulation of organochlorine pesticides in aquatic system—an overview". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 173 (1–4): 905–916. doi:10.1007/s10661-010-1433-4. PMID 20306340.

- "Technical Factsheet on: Endrin" (PDF). www.epa.gov. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Esch, G. T. van; Heemstra-Lequin, E. A. H. van (1992). Endrin (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 1–234. ISBN 92 4 157130 6. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Butler, L. C.; Staiff, D. C.; Sovocool, G. W.; Wilson, N. K.; Magnuson, J. A. (1981). "Reductive degradation of dieldrin and endrin in the field using acidified zinc". Journal of Environmental Science and Health. 16 (4): 395–408. doi:10.1080/03601238109372266. PMID 7288091.

- "Human Health Criteria". EPA Water. United States Environmental Protection Agency. December 2003. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Drinking Water Contaminants: National Primary Drinking Water Regulations". EPA Water. United States Environmental Protection Agency. May 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Classification of Pesticides by Hazard. WHO. 2010. p. 81. ISBN 978 92 4 154796 3. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

External links

- Endrin ChemSub Online, retrieved 9 April 2015