Discovery and development of gastrointestinal lipase inhibitors

Lipase inhibitors belong to a drug class that is used as an antiobesity agent. Their mode of action is to inhibit gastric and pancreatic lipases, enzymes that play an important role in the digestion of dietary fat.[2] Lipase inhibitors are classified in the ATC-classification system as A08AB (peripherally acting antiobesity products).[3] Numerous compounds have been either isolated from nature, semi-synthesized, or fully synthesized and then screened for their lipase inhibitory activity[4] but the only lipase inhibitor on the market (October 2016) is orlistat (Xenical, Alli).[5] Lipase inhibitors have also shown anticancer activity, by inhibiting fatty acid synthase.[6]

| Lipase inhibitor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Class identifiers | |

| Clinical use | Obesity |

| ATC code | A08AB01 |

| Biological target | Gastric lipase - Pancreatic lipase |

| Trade names | Xenical - Alli |

Discovery of lipase inhibitors and their development

Pancreatic lipase inhibitor was originally discovered and isolated from fermented broth of the Streptomyces toxytricini bacterium in 1981 and named lipstatin.[7] It is a selective and potent irreversible inhibitor of human gastric and pancreatic lipases. Tetrahydrolipstatin, more commonly known as orlistat, is a saturated derivative produced from hydrogen reaction. It was developed in 1983 by Hoffmann-La Roche and is a more simple and stable compound than lipstatin.[5][8][9] For that reason orlistat was chosen over lipstatin for development as an anti-obesity drug.[1][10] It is the only available FDA-approved oral lipase inhibitor and is known on the market as Xenical and Alli.[5] Initially orlistat was developed as a treatment for dyslipidemia, not as an anti-obesity agent. When researchers found out that it promotes less energy uptake, the focus was switched to obesity.[11]

Orlistat has a few adverse effects. Most reported side effects are gastrointestinal; including liquid stools, steatorrhea and abdominal pain. More severe and serious are interactions between orlistat and anticoagulants when given in combination. It can increase INR which can lead to insufficient anticoagulant treatment and bleeding.[12] These adverse effects of orlistat are more common early in the therapy but usually decrease with time. Pancreatic lipases do not only affect the hydrolysis of triglycerides but are also necessary for hydrolysis of fat soluble vitamins. Due to this, the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins may decrease. Therefore, it is recommended to take a multiple-vitamin supplement during orlistat therapy.[9][12]

Cetilistat, a new lipase inhibitor, is an experimental drug for obesity. In October 2016 the drug was still in clinical trials.[13] Cetilistat was developed to overcome the adverse effects on the gastrointestinal tract of orlistat. It has a different structure but similar inhibition activity to the gastrointestinal lipase. However cetilistat interacts differently with the fat micelles from digested food, therefore it has less side effects and better tolerability.[14]

Mechanism of action

The lipase inhibitors lipstatin and orlistat act locally in the intestinal tract. They are minimally absorbed in the circulation because of their lipophilicity.[7][15] Hence, they do not affect systemic lipases.[11]

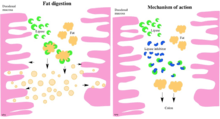

The mechanism of lipase inhibitors in fat digestion is shown in figure 1. These inhibitors bind covalently as an ester to the serine hydroxyl group at the active site on pancreatic- and gastric lipases and form a stable complex.[7][15][16] This results in a conformational change in the enzyme which causes exposing of the catalytic active site. When the active site is exposed, the hydroxyl group on the serine residue is acylated. This leads to irreversible inactivation of the enzyme. The inactive lipase is incapable of hydrolysing fats into absorbable fatty acids and monoglycerides, therefore triglycerides are excreted undigested with faeces.[15] With this mode of action calorie uptake from fat in food is limited, hence body weight is reduced.[17][18] The main role of lipase inhibitors is therefore to inhibit lipases in the gastrointestinal tract, but they do not have significant activity against proteases, amylases or other digestive enzymes.[11]

Cetilistat has a bicyclic structure but lacks the β-lactone ring. It acts in a similar way as a typical lipase inhibitor that has the β-lactone structure.[4][17]

Shift towards cancer treatment

As further discussed, orlistat is a pancreatic and gastric lipase inhibitor. Orlistat is also a potent thioesterase inhibitor and therefore inhibits fatty acid synthase (FAS). Since FAS is essential for tumor cells, for its growth and survival, and is upregulated and overexpressed in variety of tumors,[19] scientists have high expectations for FAS as an oncology drug target.[20] Orlistat inhibits FAS with the same mechanism as it does with pancreatic lipase, that is by binding covalently to the active serine site.[20] This effect of orlistat as a FAS-inhibitor was first identified in a high throughput screening for enzymes with prostate cancer inhibition activity. However FAS is resistant to many cancer medicines. Orlistat sensitizes these FAS resistance cancer drugs, by inhibiting FAS.[21] There is a low FAS expression in normal tissues so the activity of orlistat on normal cells is limited. Because of the difference in FAS expression between normal cells and cancer cells, orlistat selectively targets tumor cells. Due to this FAS is a potential drug target in cancer therapy.[19][22]

Orlistat works locally in the intestines as a lipase inhibitor, and therefore suffers from several limitations in its development as a systemic drug. It is poor bioavailability and solubility are the main reasons to develop a new anticancer analogue to overcome these limitations.[6][19]

Drug target

Lipases in the gastrointestinal tract play a critical role in fat digestion. More than 95% of fat in food consists of triglycerides, which are categorized based on the length of fatty acids connected to glyceride backbone.[23] The length of long-chain triglycerides prevent their absorption through the intestinal mucosa.[24] For that reason lipases in the gastrointestinal tract must hydrolyse it to smaller molecules, free fatty acids and monoglyceride,[25] before absorption can occur.[26]

Gastric lipase

Gastric- and lingual lipases are the two acidic lipolytic enzymes that origin preduodenal but the gastric lipase is in much higher levels in humans. Gastric lipase is synthesized and secreted from gastric chief cells in the stomach and is stable at pH 1,5-8,[26] but has maximum activity at pH 3-6.[25] Fat digestion begins when gastric lipase hydrolyses dietary triglycerides, by cleaving only one long-, medium- or short-acyl chain from the glyceride backbone and release free fatty acids and diacylglycerols. The enzyme hydrolyses esters at position sn-3, the acyl chain at the bottom, more rapidly than esters at sn-1 position, the acyl chain on the top of the glyceride backbone. However the gastric lipase activity against phospholipids and cholesterol esters is poor.

Gastric lipase is composed of 379 amino acids. Fully glycosylated protein is 50kDa and unglycosylated enzyme is 43kDa. However deglycosylation of the enzyme does not affect the activity of the enzyme.[26] The hydrophobic region around Ser152, which has the hexapeptide sequence Val-Gly-His-Ser-Gln-Gly, is essential for the catalytic activity of gastric lipase. At the N-terminal, Lys4 is necessary for the enzyme to bind at lipid-water interfaces.[26]

Pancreatic lipase

Pancreatic lipase is the most important lipolytic enzyme in the gastrointestinal tract[26] and is essential for fat digestion.[28] Pancreatic lipase is secreted from acinar cells in the pancreas[29] and its secretion, with the pancreatic juice to the small intestine, is stimulated by hormones. These hormones are induced in the stomach by hydrolysed products in gastric digestion.[30][31] The pancreatic lipase is secreted to the small intestine where it is most active, at pH 7-7,5.[25] Pancreatic lipase hydrolyses triglycerides and diglycerides by cleaving acyl chains at the sn-1 and sn-3 position[26] and releases free fatty acids and 2-monoglycerides.[28]

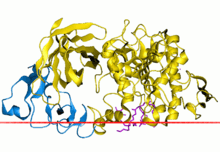

The pancreatic lipase consists of 465 amino acids. Schematic picture of pancreatic lipase is shown in figure 2. Pancreatic and gastric lipases share little homology but have the same hydrophobic region at the active site, which is important for the lipolytic activity. The hydrophobic region has the hexapeptide sequence Val-Gly-His-Ser-Gln-Gly and is at Ser153 in pancreatic lipases but Ser152 in gastric lipases.[26]

Chemistry of lipase inhibitors

Structure-activity relationship (SAR)

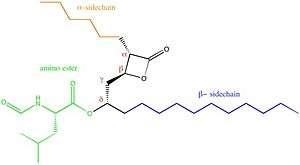

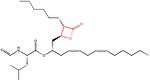

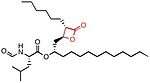

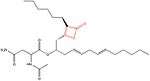

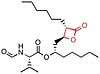

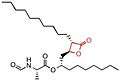

The chemical structure of compounds play an important role in binding to their target. The most important and necessary chemical group for the binding and activity of these compounds is the β-lactone (beta-lactone) ring which is the central pharmacophore. The β-lactone moiety is shown in red in the structures in the table below. Researches have shown that cleavage of the β-lactone ring results in loss of inhibitory activity of the inhibitors, which makes the β-lactone structure a crucial part in biological activity.[5][8] The lactone ring structure binds irreversibly to the active site of the lipase and forms covalent bond, which leads to inhibition.[32] Most natural lipase inhibitors differ only in the structure of the side chains and the nature of the linked amino acids, but have the same β-lactone ring[5] in (S)-configuration as a primary structure.[1] Besides the role of the β-lactone ring in structure-activity relationship, the nature of the functional groups (e.g. ester or ether and the chain length at the β-site) also matter.[4] However a trans-position of the side-chains on the β-lactone ring is crucial for its activity.[33]

| Lipstatin | Orlistat | Esterastin | Valilactone | Panclicin D | Ebelactone | Vibralactone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

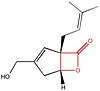

| Structure |  insert a caption here |

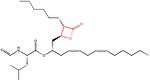

insert a caption here |

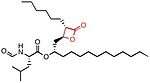

insert a caption here |

insert a caption here |

insert a caption here |

insert a caption here |

insert a caption here |

| IC50 value | 6,9 · 10−2 µg/ml[1] | 1,2 · 10−1 µg/ml[1] | 2,0 · 10−1 µg/ml[1] | 1,4 · 10−4 µg/ml[1] | 3,9 · 10−1 µg/ml[1] | 1,0 · 10−3 µg/ml[1] | 4,0 · 10−1 µg/ml[1] |

| Lipstatin | |

|---|---|

| Structure |  insert a caption here |

| IUPAC | [(2S,4Z,7Z)-1-[(2S,3R)-3-hexyl-4-oxooxetan-2-yl]

trideca-4,7-dien-2-yl] (2S)-2-formamido-4-methylpentanoate[34] |

| Chemical formula | C29H49NO5[34] |

| Molar mass (g/mol) | 491,7[34] |

| Orlistat | |

|---|---|

| Structure |  insert a caption here |

| IUPAC | [(2S)-1-[(2S,3S)-3-hexyl-4-oxooxetan-2-yl]tri

decan-2-yl]- (2S)-2-formamido -4-methylpentanoate[35] |

| Chemical formula | C29H35NO5[35] |

| Molar mass (g/mol) | 495,7[35] |

| Cetilistat | |

|---|---|

| Structure | |

| IUPAC | 2-hexadecoxy-6-methyl-3,1-benzoxazin-4-one[36] |

| Chemical formula | C25H39NO3[36] |

| Molar mass (g/mol) | 401,6[36] |

Lipase inhibitors

Lipstatin, the first lipase inhbitor,[4] comes from a natural source. It has a β-propiolactone ring, which has a 2,3-trans-disubstituted linear alkyl chains located at the α- (C6) and β-site (C13) of the compound. It contains N-formyl-L-leucine amino acid connected to the β-alkyl chain via ester-bond.[5] The structure and more information about Lipstatin is shown in the table on the right.[34]

Orlistat is a semi-synthetic compound, which has a similar structure to lipstatin. They differ only in the saturation of the β-alkyl chain, where orlistat is saturated while lipstatin has two double bonds in the side chain.[37] The structure and more information about Orlistat is shown in the table on the right.[35]

Cetilistat is a synthetic lipase inhibitor. Instead of having a β-lactone structure like most of the lipase inhibitors,[17] it has a bicyclic benzoxazinone ring. It is also a lipophilic compound but differs in the hydro- and lipophilic side chain.[14] The structure and more information about Cetilistat is shown in the table on the right.[36]

Other lipase inhibitors have been recognized, e.g. from different plant products. These include alkaloids, carotenoids, glycosides, polyphenols, polysaccharides, saponins and terpenoids. However, none of these have been used clinically as lipase inhibitors. More active lipase inhibitors are the lipophilic compounds from microbial sources.[4] Lipase inhibitors from microbial source can be divided into two classes based on their structure. Those who have a β-lactone ring are lipstatin, valilactone, percyquinin, panclicin A-E, ebelactone A and B, vibralactone and esterastin. Those who do not have a β-lactone ring are (E)-4-amino styryl acetate, ε–polylysine and caulerpenyne.[8] Lipase inhibitors have also been made synthetically, e.g. cetilistat, based on the structure of triglycerides and other natural lipase substrates.[8] However, the synthetic lipase inhibitors differ in structure and some of them lack the β-lactone ring.[4]

References

- Schaefer, B., Natural Products in the Chemical Industry. 2015: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Guerciolini, R., Mode of action of orlistat. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 1997. 21: p. S12-23.

- "All centralized human medicinal product by ATC code". Public Health. European Commission. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Lunagariya, N.A., et al., Inhibitors of pancreatic lipase: state of the art and clinical perspectives. EXCLI Journal, 2014. 13: p. 897-921.

- Bai, T., et al., Operon for biosynthesis of lipstatin, the beta-lactone inhibitor of human pancreatic lipase. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014. 80(24): p. 7473-7483.

- Purohit, V.C., et al., Practical, Catalytic, Asymmetric Synthesis of β-Lactones via a Sequential Ketene Dimerization/Hydrogenation Process: Inhibitors of the Thioesterase Domain of Fatty Acid Synthase. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2006. 71(12): p. 4549-4558.

- Medeiros-Neto, G., A. Halpern, and C. Bouchard, Progress in Obesity Research: 9. Orlistat in the treatment of obesity, ed. A. Halpern. 2003: Food & Nutrition Press.

- Birari, R.B. and K.K. Bhutani, Pancreatic lipase inhibitors from natural sources: unexplored potential. Drug Discovery Today, 2007. 12(19–20): p. 879-889.

- Heck, A.M., J.A. Yanovski, and K.A. Calis, Orlistat, a New Lipase Inhibitor for the Management of Obesity. Pharmacotherapy, 2000. 20(3): p. 270-279.

- Pommier, A., J.-M. Pons, and P.J. Kocienski, The First Total Synthesis of (-)-Lipstatin. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 1995. 60(22): p. 7334-7339.

- Wilding, J.P.H., Pharmacotherapy of Obesity. Intestinal lipase inhibitors, ed. J.P.H. Wilding. 2008: Birkhäuser Basel.

- "Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). Xenical. European Medicines Agency. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Questions and Answers about FDA's Initiative Against Contaminated Weight Loss Products". U.S Food And Drug Administration. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Bryson, A., S. de la Motte, and C. Dunk, Reduction of dietary fat absorption by the novel gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor cetilistat in healthy volunteers. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2009. 67(3): p. 309-315.

- Al-Suwailem, A., et al., Safety and Mechanism of Action of Orlistat (Tetrahydrolipstatin) as the First Local Antiobesity Drug. Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 2006. 2(4): p. 205-208..

- Bray, G.A., L.S. University, and D. Ryan, Overweight and the Metabolic Syndrome: From Bench to Bedside. Ectopic Fat and the Metabolic Syndrome, ed. F.G.S. Toledo and D.E. Kelley. 2007: Springer US.

- Padwal, R., Cetilistat, a new lipase inhibitor for the treatment of obesity. Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs, 2008. 9(4): p. 414-421.

- Gras, J., Cetilistat for the treatment of obesity. Drugs Today (Barc), 2013. 49(12): 755-9.

- Flavin, R., et al., Fatty acid synthase as a potential therapeutic target in cancer. Future Oncol, 2010. 6(4): p. 551-562.

- Richardson, R.D., et al., Synthesis of Novel β-Lactone Inhibitors of Fatty Acid Synthase. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 2008. 51(17): p. 5285-5296.

- Fako, V.E., J.-T. Zhang, and J.-Y. Liu, Mechanism of Orlistat Hydrolysis by the Thioesterase of Human Fatty Acid Synthase. ACS Catalysis, 2014. 4(10): p. 3444-3453.

- R. Pandey, P., et al., Anti-Cancer Drugs Targeting Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS). Recent Patents on Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery, 2012. 7(2): p. 185-197.

- Vaclavik, V., & Christian, E. W. (2007). Essentials of Food Science: Springer New York.

- Chow, B. P. C., Shaffer, E. A., & Parsons, H. G. (1990). Absorption of triglycerides in the absence of lipase. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 68(4), 519-523. doi:10.1139/y90-074

- Müller, G. and S. Petry, Lipases and Phospholipases in Drug Development: From Biochemistry to Molecular Pharmacology. Physiology of Gastrointestinal Lipolysis and Therapeutical Use of Lipases and Digestive Lipase Inhibitors. 2006: Wiley.

- Christophe, A.B. and S. DeVriese, Fat Digestion and Absorption. Enzymatic Aspects of Fat Digestion in the Gastrointestinal Tract, ed. R.-D. Duan. 2000: AOCS Press.

- Chen, B., et al., Morphing Activity between Structurally Similar Enzymes: From Heme-Free Bromoperoxidase to Lipase. Biochemistry, 2009. 48(48): p. 11496-11504

- Johnson, L.R., Gastrointestinal Physiology. Digestion and absorption of nutrients. 2013: Elsevier Mosby.

- Mansbach, C.M., P. Tso, and A. Kuksis, Intestinal Lipid Metabolism. Molecular Mechanisms of Pancreatic Lipase and Colipase, ed. M.E. Lowe. 2011: Springer US.

- Shahidi, F., Nutraceutical and Specialty Lipids and their Co-Products. StructureRelated Effects on Absorption and Metabolism of Nutraceutical and Specialty Lipids. 2006: CRC Press.

- Christophe, A.B. and S. DeVriese, Fat Digestion and Absorption. Effects of Triacylglycerol Structure on Fat Absorption, ed. C.-E. Høy and H. Mu. 2000: AOCS Press.

- Yadav, J.S., et al., Stereoselective synthesis of (−)-tetrahydrolipstatin via a radical cyclization based strategy. Tetrahedron Letters, 2006. 47(26): p. 4393-4395.

- Bodkin, J.A., E.J. Humphries, and M.D. McLeod, The Total Synthesis of (–)-Tetrahydrolipstatin. Australian journal of chemistry, 2003. 56(8): p. 795-803.

- "(-)-Lipstatin". PubChem Compound Database. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Orlistat". PubChem Compound Database. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Cetilistat". PubChem Compound Database. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Christophe, A.B. and S. DeVriese, Fat Digestion and Absorption. The Role of Dietary Fat in Obesity and Therapy with Orlistat, ed. A. Golay. 2000: AOCS Press.