Brodmann area 10

Brodmann area 10 (BA10, frontopolar prefrontal cortex, rostrolateral prefrontal cortex, or anterior prefrontal cortex) is the anterior-most portion of the prefrontal cortex in the human brain.[1] BA10 was originally defined broadly in terms of its cytoarchitectonic traits as they were observed in the brains of cadavers, but because modern functional imaging cannot precisely identify these boundaries, the terms anterior prefrontal cortex, rostral prefrontal cortex and frontopolar prefrontal cortex are used to refer to the area in the most anterior part of the frontal cortex that approximately covers BA10—simply to emphasize the fact that BA10 does not include all parts of the prefrontal cortex.

| Brodmann area 10 | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Area frontopolaris |

| NeuroNames | 76 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1741 |

| FMA | 68607 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

BA10 is the largest cytoarchitectonic area in the human brain. It has been described as "one of the least well understood regions of the human brain".[2] Present research suggests that it is involved in strategic processes in memory recall and various executive functions. During human evolution, the functions in this area resulted in its expansion relative to the rest of the brain.[3]

Anatomy

Size

The volume of the human BA10 is about 14 cm3 and constitutes roughly 1.2% of total brain volume. This is twice what would be expected in a hominoid with a human-sized brain. By comparison, the volume of BA10 in bonobos is about 2.8 cm3, and makes up only 0.74% of its brain volume. In each hemisphere, area 10 contains an estimated 250 million neurons.[3]

Location

BA10 is a subdivision of the cytoarchitecturally defined frontal region of cerebral cortex. It occupies the most rostral portions of the superior frontal gyrus and the middle frontal gyrus. In humans, on the medial aspect of the hemisphere it is bounded ventrally by the superior rostral sulcus. It does not extend as far as the cingulate sulcus. Cytoarchitecturally it is bounded dorsally by the granular frontal area 9, caudally by the middle frontal area 46, and ventrally by the orbital area 47 and by the rostral area 12 or, in an early version of Brodmann's cortical map (Brodmann-1909), the prefrontal Brodmann area 11-1909.[4]

Area 10 lies on top of a bony air sinus which has limited Electrophysiology research upon it.[5]

Relation to frontal pole

In humans the frontal pole area of the prefrontal cortex includes not only area 10 but part of BA 9. BA 10 also extends beyond the pole area into its ventromedial side. In Guenon monkeys, the pole area is filled by BA 12 (and its BA 10 is found in the orbital prefrontal region).[2]

Cytoarchitecture

In humans the six cortical layers of area 10 have been described as having a "remarkably homogeneous appearance".[3] All of them are readily identified. Relative to each other, layer I is thin to medium in width making up 11% of the depth of area 10. Layer II is thin and contains small granular and pyramidal medium to dark staining cells (in terms of Nissl staining) which colors RNA and DNA. The widest layer is III. Its pyramidal neurons are smaller nearer the above layer II than the below layer IV. Like layer II its cells are medium to dark. Layers II and III make up 43% of the cortex depth. Layer IV has clear borders with layers III above and V below and it is thin. Its cells are pale to medium in staining. Layer V is wide and contains two distinct sublayers, Va and Vb. The density of cells Va is greater than in Vb and have darker staining. Layers IV and V make up 40% of cortical thickness. Layer VI below layer V and above the white matter contains dark pyramidal and fusiform neurons. It contributes 6% of area 10 thickness.[3]

Area 10 differs from the adjacent Brodmann 9 in that the latter has a more distinct layer Vb and more prominent layer II. Neighbouring Brodmann area 11 compared to area 10 has a thinner layer IV with more prominent layers Va, Vb and II.[3]

Area 10 in humans has the lowest neuron density among primate brains.[3] It is also unusual in that its neurons have particularly extensive dendritic arborization and are highly dense with dendritic spines.[6] This situation has been suggested to enable integration of inputs from multiple areas.[2]

Subareas

BA 10 is divided into three sub-areas, 10p, 10m and 10r. 10p occupies the frontal pole while the other two cover the ventromedial part of the prefrontal cortex.[7] Area 10m has thin layers II and IV and a more prominent layer V. In contrast, area 10r has a prominent layer II and a thicker layer IV. Large pyramidal cells are also present in 10r layer III and even more so in area 10p. But it is noted that the "differences between the three areas are gradual, however, and it is difficult to draw sharp boundaries between them".[7]

Connections

Research upon primates suggests that area 10 has inputs and output connections with other higher-order association cortex areas particularly in the prefrontal cortex while having few with primary sensory or motor areas. Its connections through the extreme capsule link it to the auditory and multisensory areas of the superior temporal sulcus. They also continue in the medial longitudinal fasciculus in the white matter of the superior temporal gyrus areas on the superior temporal gyrus (areas TAa, TS2, and TS3) and nearby multisensory areas on the upper bank of the superior temporal sulcus (TPO). Another area connected through the extreme capsule is the ventral region of the insula. Connections through the cingulate fasciculus link area 10 to the anterior, posterior cingulate cortex, and retrosplenial cortex. The uncinate fasciculus connects it with the amygdala, temporopolar proisocortex and anterior most part of the superior temporal gyrus. There are no connections to the parietal cortex, occipital cortex nor inferotemporal cortex[8]

Its connections have been summarized as "it seems not to be interconnected with ‘downstream’ areas in the way that other prefrontal areas are. .. it is the only prefrontal region that is predominantly (and possibly exclusively) interconnected with supramodal cortex in the PFC, anterior temporal cortex and cingulate cortex."[9] It has been proposed that due to this connectivity that it can "play a major role in the highest level of integration of information coming from visual, auditory, and somatic sensory systems to achieve amodal, abstract, conceptual interpretation of the environment .. and may be the anatomical basis for the suggested role of the rostral prefrontal cortex in influencing abstract information processing and the integration of the outcomes of multiple cognitive operations".[8]

Evolution

Katerina Semendeferi and colleagues has suggested that "During hominid evolution, area 10 underwent a couple of .. changes: one involves a considerable increase in overall size, and the other involves a specific increase in connectivity, especially with other higher-order association areas."[3]

Cranial endocasts taken from the inside of the skull of Homo floresiensis show an expansion in the frontal polar region suggesting enlargement in its Brodmann's area 10.[10]

Function

Although this region is extensive in humans, its function is poorly understood.[3] Koechlin & Hyafil have proposed that processing of 'cognitive branching' is the core function of the frontopolar cortex.[11] Cognitive branching enables a previously running task to be maintained in a pending state for subsequent retrieval and execution upon completion of the ongoing one. Many of our complex behaviors and mental activities require simultaneous engagement of multiple tasks, and they suggest the anterior prefrontal cortex may perform a domain-general function in these scheduling operations. Thus, the frontopolar cortex shares features with the central executive in Baddeley's model of working memory. However, other hypotheses have also been proffered, such as those by Burgess et al..[12] These also take into consideration the influence of the limbic system, to which the frontopolar cortex is connected through the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. A 2006 meta-analysis found that the rostral prefrontal cortex was involved in working memory, episodic memory and multiple-task coordination.[13] This area has also been implicated in decision making prior to the decision being available to conscious awareness [14]

Images

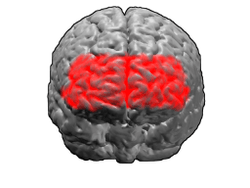

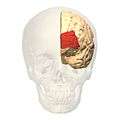

Animation.

Animation. front view.

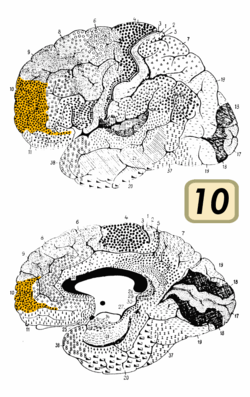

front view. Lateral view.

Lateral view. Medial view.

Medial view.

See also

References

- Knowlton, Barbara J.; Morrison, Robert G.; Hummel, John E.; Holyoak, Keith J. (July 2012). "A neurocomputational system for relational reasoning". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 16 (7): 373–381. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.06.002. PMID 22717468.

- Ramnani, N; Owen, AM (2004). "Anterior prefrontal cortex: insights into function from anatomy and neuroimaging". Nat Rev Neurosci. 5 (3): 184–94. doi:10.1038/nrn1343. PMID 14976518.

- Semendeferi, K; Armstrong, E; Schleicher, A; Zilles, K; Van Hoesen, GW (2001). "Prefrontal cortex in humans and apes: a comparative study of area 10". Am J Phys Anthropol. 114 (3): 224–41. doi:10.1002/1096-8644(200103)114:3<224::AID-AJPA1022>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID 11241188.

-

- Wallis, JD (2010). "Polar exploration". Nat Neurosci. 13 (1): 7–8. doi:10.1038/nn0110-7. PMID 20033080.

- Jacobs, B; Schall, M; Prather, M; Kapler, E; Driscoll, L; Baca, S; Jacobs, J; Ford, K; Wainwright, M; Treml, M (2001). "Regional dendritic and spine variation in human cerebral cortex: a quantitative golgi study". Cereb Cortex. 11 (6): 558–71. doi:10.1093/cercor/11.6.558. PMID 11375917.

- Ongür, D; Ferry, AT; Price, JL (2003). "Architectonic subdivision of the human orbital and medial prefrontal cortex". J Comp Neurol. 460 (3): 425–49. doi:10.1002/cne.10609. PMID 12692859.

- Petrides, M; Pandya, DN (2007). "Efferent association pathways from the rostral prefrontal cortex in the macaque monkey". J Neurosci. 27 (43): 11573–86. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2419-07.2007. PMID 17959800.

- Ramnani N, Owen AM. (2004). Anterior prefrontal cortex: insights into function from anatomy and neuroimaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. Mar;5(3):184-94. doi:10.1038/nrn1343 PMID 14976518

- Falk, D; Hildebolt, C; Smith, K; Morwood, MJ; Sutikna, T; Brown, P; Jatmiko, Saptomo EW; Brunsden, B; Prior, F (2005). "The brain of LB1, Homo floresiensis". Science. 308 (5719): 242–5. doi:10.1126/science.1109727. PMID 15749690.

- Koechlin, E.; Hyafil, A. (2007). "Anterior prefrontal function and the limits of human-decision making". Science. 318 (5850): 594–598. doi:10.1126/science.1142995. PMID 17962551.

- Burgess, P.W.; Dumontheil, I.; Gilbert, S.J. (2007). "The gateway hypothesis of rostral prefrontal cortex (area 10) function". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 11 (7): 290–298. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.578.2743. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.004. PMID 17548231.

- Gilbert, Sam J.; Spengler, Stephanie; Simons, Jon S.; Steele, J. Douglas; Lawrie, Stephen M.; Frith, Christopher D.; Burgess, Paul W. (2006-06-01). "Functional specialization within rostral prefrontal cortex (area 10): a meta-analysis". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 18 (6): 932–948. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.530.7540. doi:10.1162/jocn.2006.18.6.932. ISSN 0898-929X. PMID 16839301.

- Soon, Brass, Heinze and Haynes, 2008. Nature Neuroscience

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brodmann area 10. |

- ancil-56 at NeuroNames - "frontopolar area 10"

- ancil-58 at NeuroNames - "Brodmann area 10"

- Brede Database Brodmann area 10

- BrainMaps Area 10 Of Prefrontal Cortex

- Is Brodmann Area 10 the Key to Human Evolution?