Entorhinal cortex

The entorhinal cortex (EC) is an area of the brain located in the medial temporal lobe and functions as a hub in a widespread network for memory, navigation and the perception of time.[1] The EC is the main interface between the hippocampus and neocortex. The EC-hippocampus system plays an important role in declarative (autobiographical/episodic/semantic) memories and in particular spatial memories including memory formation, memory consolidation, and memory optimization in sleep. The EC is also responsible for the pre-processing (familiarity) of the input signals in the reflex nictitating membrane response of classical trace conditioning, the association of impulses from the eye and the ear occurs in the entorhinal cortex.

| Entorhinal cortex | |

|---|---|

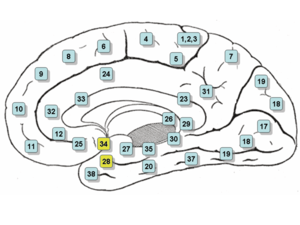

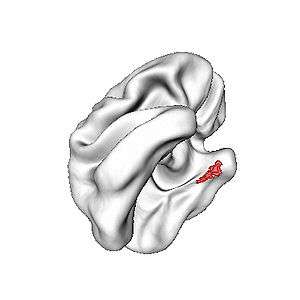

Medial surface. (Entorhinal cortex approximately maps to areas 28 and 34, at lower left.) | |

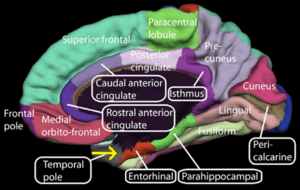

Medial surface of right hemisphere. Entorhinal cortex visible at near bottom. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | ɛntəɹ'ɪnəl |

| Part of | Temporal lobe |

| Artery | Posterior cerebral Choroid |

| Vein | Inferior striate |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cortex entorhinalis |

| MeSH | D018728 |

| NeuroNames | 168 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1508 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Structure

In rodents, the EC is located at the caudal end of the temporal lobe. In primates it is located at the rostral end of the temporal lobe and stretches dorsolaterally. It is usually divided into medial and lateral regions with three bands with distinct properties and connectivity running perpendicular across the whole area. A distinguishing characteristic of the EC is the lack of cell bodies where layer IV should be; this layer is called the lamina dissecans.

Connections

The superficial layers – layers II and III – of EC project to the dentate gyrus and hippocampus: Layer II projects primarily to dentate gyrus and hippocampal region CA3; layer III projects primarily to hippocampal region CA1 and the subiculum. These layers receive input from other cortical areas, especially associational, perirhinal, and parahippocampal cortices, as well as prefrontal cortex. EC as a whole, therefore, receives highly processed input from every sensory modality, as well as input relating to ongoing cognitive processes, though it should be stressed that, within EC, this information remains at least partially segregated.

The deep layers, especially layer V, receive one of the three main outputs of the hippocampus and, in turn, reciprocate connections from other cortical areas that project to superficial EC.

The rodent entorhinal cortex shows a modular organization, with different properties and connections in different areas.

Brodmann's areas

- Brodmann area 28 is known as the "area entorhinalis"

- Brodmann area 34 is known as the "area entorhinalis dorsalis"

Function

Neuron information processing

In 2005, it was discovered that entorhinal cortex contains a neural map of the spatial environment in rats.[2] In 2014, John O'Keefe, May-Britt Moser and Edvard Moser received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, partly because of this discovery.[3]

Neurons in the lateral entorhinal cortex exhibit little spatial selectivity,[4] whereas neurons of the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC), exhibit multiple "place fields" that are arranged in a hexagonal pattern, and are, therefore, called "grid cells". These fields and spacing between fields increase from the dorso-lateral MEA to the ventro-medial MEA.[2][5]

The same group of researchers have found speed cells in the medial entorhinal cortex of rats. The speed of movement is translated from proprioceptive information and is represented as firing rates in these cells. The cells are known to fire in correlation to future speed of the rodent.[6]

Single-unit recording of neurons in humans playing video games find path cells in the EC, the activity of which indicates whether a person is taking a clockwise or counterclockwise path. Such EC "direction" path cells show this directional activity irrespective of the location of where a person experiences themselves, which contrasts them to place cells in the hippocampus, which are activated by specific locations.[7]

EC neurons process general information such as directional activity in the environment, which contrasts to that of the hippocampal neurons, which usually encode information about specific places. This suggests that EC encodes general properties about current contexts that are then used by hippocampus to create unique representations from combinations of these properties.[7]

Research generally highlights a useful distinction in which the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) mainly supports processing of space[8], whereas the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC) mainly supports the processing of time[1].

Individual variation in the volume of EC is linked to taste perception. People with a larger EC in the left hemisphere found quinine, the source of bitterness in tonic water, less bitter. [9]

Clinical significance

Alzheimer's disease

The entorhinal cortex is the first area of the brain to be affected in Alzheimer's disease; a recent functional magnetic resonance imaging study has localised the area to the lateral entorhinal cortex.[10] Lopez et al.[11] have shown, in a multimodal study, that there are differences in the volume of the left entorhinal cortex between progressing (to Alzheimer's disease) and stable mild cognitive impairment patients. These authors also found that the volume of the left entorhinal cortex inversely correlates with the level of alpha band phase synchronization between the right anterior cingulate and temporo-occipital regions.

In 2012, neuroscientists at UCLA conducted an experiment using a virtual taxi video game connected to seven epilepsy patients with electrodes already implanted in their brains, allowing the researchers to monitor neuronal activity whenever memories were being formed. As the researchers stimulated the nerve fibers of each of the patients' entorhinal cortex as they were learning, they were then able to better navigate themselves through various routes and recognize landmarks more quickly. This signified an improvement in the patients' spatial memory.[12]

Effect of aerobic exercise

A study finds that regardless of gender, young adults who have greater aerobic fitness also have greater volume of their entorhinal cortex. It suggests that aerobic exercise may have a positive effect on the medial temporal lobe memory system (which includes the entorhinal cortex) in healthy young adults. This also suggests that exercise training, when designed to increase aerobic fitness, might have a positive effect on the brain in healthy young adults[13]

References

- Integrating time from experience in the lateral entorhinal cortex Albert Tsao, Jørgen Sugar, Li Lu, Cheng Wang, James J. Knierim, May-Britt Moser & Edvard I. Moser Naturevolume 561, pages57–62 (2018)

- Hafting T, Fyhn M, Molden S, Moser M, Moser E (2005). "Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex". Nature. 436 (7052): 801–6. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..801H. doi:10.1038/nature03721. PMID 15965463.

- "Overview of Nobel Prize laureates in Physiology or Medicine".

- Hargreaves E, Rao G, Lee I, Knierim J (2005). "Major dissociation between medial and lateral entorhinal input to dorsal hippocampus". Science. 308 (5729): 1792–4. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1792H. doi:10.1126/science.1110449. PMID 15961670.

- Fyhn M, Molden S, Witter M, Moser E, Moser M (2004). "Spatial representation in the entorhinal cortex". Science. 305 (5688): 1258–64. Bibcode:2004Sci...305.1258F. doi:10.1126/science.1099901. PMID 15333832.

- Kropff Em; Carmichael J E; Moser M-B; Moser E-I (2015). "Speed cells in the medial entorhinal cortex". Nature. 523 (7561): 419–424. Bibcode:2015Natur.523..419K. doi:10.1038/nature14622. hdl:11336/10493. PMID 26176924.

- Jacobs J, Kahana MJ, Ekstrom AD, Mollison MV, Fried I (2010). "A sense of direction in human entorhinal cortex". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (14): 6487–6492. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.6487J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911213107. PMC 2851993. PMID 20308554.

- Schmidt-Hieber, Christoph; Häusser, Michael (2013). "Cellular mechanisms of spatial navigation in the medial entorhinal cortex". Nature. 16 (3): 325–331. doi:10.1038/nn.3340. PMID 23396102.

- Hwang LD, Strike LT, Couvy-Duchesne B, de Zubicaray GI, McMahon K, Bresline PA, Reed DR, Martin NG, Wright MJ (2019). "Associations between brain structure and perceived intensity of sweet and bitter tastes". Behav. Brain Res. 2 (363): 103–108. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2019.01.046. PMC 6470356. PMID 30703394.

- Khan UA, Liu L, Provenzano FA, Berman DE, Profaci CP, Sloan R, Mayeux R, Duff KE, Small SA (2013). "Molecular drivers and cortical spread of lateral entorhinal cortex dysfunction in preclinical Alzheimer's disease". Nature Neuroscience. 17 (2): 304–311. doi:10.1038/nn.3606. PMC 4044925. PMID 24362760.

- Lopez, M. E.; Bruna, R.; Aurtenetxe, S.; Pineda-Pardo, J. A.; Marcos, A.; Arrazola, J.; Reinoso, A. I.; Montejo, P.; Bajo, R.; Maestu, F. (2014). "Alpha-Band Hypersynchronization in Progressive Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Magnetoencephalography Study". Journal of Neuroscience. 34 (44): 14551–14559. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0964-14.2014. PMC 6608420. PMID 25355209.

- Suthana, N.; Haneef, Z.; Stern, J.; Mukamel, R.; Behnke, E.; Knowlton, B.; Fried, I. (2012). "Memory Enhancement and Deep-Brain Stimulation of the Entorhinal Area". New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (6): 502–510. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1107212. PMC 3447081. PMID 22316444.

- "Study highlights the importance of physical activity and aerobic exercise for healthy brain function". Retrieved 2017-12-04.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Entorhinal cortex. |

- Stained brain slice images which include the "Entorhinal cortex" at the BrainMaps project

- NIF Search - Entorhinal Cortex via the Neuroscience Information Framework

For delineating the Entorhinal cortex, see Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Killiany RJ. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006 Jul 1;31(3):968-80.