Basic airway management

Basic airway management are a set of medical procedures performed in order to prevent airway obstruction and thus ensuring an open pathway between a patient’s lungs and the outside world. This is accomplished by clearing or preventing obstructions of airways, often referred to as choking, cause by the tongue, the airways themselves, foreign bodies or materials from the body itself, such as blood or aspiration. Contrary to advanced airway management; minimal-invasive techniques does not rely on the use of medical equipment and can be performed without or with little training. Airway management is a primary consideration in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, anaesthesia, emergency medicine, intensive care medicine and first aid.

Evaluation

Conscious

Symptoms of airway obstructions includes:

- The person cannot speak or cry out, or has great difficulty and limited ability to do so.

- Breathing, if possible, is labored, producing gasping or wheezing.

- The person has a violent and largely involuntary cough, gurgle, or vomiting noise, though more serious choking victims will have a limited (if any) ability to produce these symptoms since they require at least some air movement.

- The person desperately clutches his or her throat or mouth, or attempts to induce vomiting by putting their fingers down their throat.

- If breathing is not restored, the person's face turns blue (cyanosis) from lack of oxygen.

Unconscious

Evaluation of an unconscious patients breathing is often performed by the look, listen, and feel method. The ear is placed over person's mouth so breathing can be heard and felt while looking for rising chest or abdomen. The procedure should not take longer than 10 seconds. As in conscious patients stridor can be heard if there is an airway obstruction. Back fall of the tongue however results in snoring. In the unconscious patient agonal breathing is often mistaken for airway obstructions. If there is respiratory arrest or agonal breathing CPR is indicated.

Treatment

Treatment includes a number of procedures aiming at removing foreign bodies from the airways. Most modern protocols, including those of the American Heart Association, American Red Cross and the European Resuscitation Council,[1] recommend several stages, designed to apply increasingly more pressure. Basic treatment includes a number of procedures aiming at removing foreign bodies from the airways. Most protocols recommend encouraging the victim to cough, followed by hard back slaps and if none of these things work; abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver) or chest thrusts. Some guidelines recommend alternating between abdominal thrusts and back slaps.[1]

Encouraging the victim to cough

This stage was introduced in many protocols as it was found that many people were too quick to undertake potentially dangerous interventions, such as abdominal thrusts, for items which could have been dislodged without intervention. Also, if the choking is caused by an irritating substance rather than an obstructing one, and if conscious, the patient should be allowed to drink water on their own to try to clear the throat. Since the airway is already closed, there is very little danger of water entering the lungs. Coughing is normal after most of the irritant has cleared, and at this point the patient will probably refuse any additional water for a short time.

Back blows

Most protocols recommend encouraging the victim to cough, followed by hard back slaps with the heel of the hand on the upper back of the victim. The number to be used varies by training organization, but is usually between five and twenty. For example, the European Resuscitation Council and the Mayo Clinic recommends five blows between the shoulder blades.[1][2] The back slap is designed to use percussion to create pressure behind the blockage, assisting the patient in dislodging the article. In some cases the physical vibration of the action may also be enough to cause movement of the article sufficient to allow clearance of the airway.

Abdominal thrusts

Performing abdominal thrusts involves a rescuer standing behind a patient and using his or her hands to exert pressure on the bottom of the diaphragm. This compresses the lungs and exerts pressure on any object lodged in the trachea, hopefully expelling it. The European Resuscitation Council and the Mayo Clinic recommend alternating between 5 back slaps and 5 abdominal thrusts in severe airway obstructions.[1][2] In some areas, such as Australia, authorities believe that there is not enough scientific evidence to support the use of abdominal thrusts and their use is not recommended in first aid. Instead, chest thrusts are recommended.[3] A person may also perform abdominal thrusts on himself by using a fixed object such as a railing or the back of a chair to apply pressure where a rescuer's hands would normally do so. As with other forms of the procedure, it is possible that internal injuries may result.

Finger sweep

The American Medical Association advocates sweeping the fingers across the back of the throat to attempt to dislodge airway obstructions, once the choking victim becomes unconscious.[4] However, many modern protocols recommend against the use of the finger sweep since, if the patient is conscious, they will be able to remove the foreign object themselves, or if they are unconscious, the rescuer should simply place them in the recovery position as this allows (to a certain extent) the drainage of fluids out of the mouth instead of down the trachea due to gravity. There is also a risk of causing further damage (for instance inducing vomiting) by using a finger sweep technique.

Prevention

Prevention techniques focuses on preventing the tongue from falling back and obstructing the airways, such as head-tilt/chin-lift and jaw-thrust maneuvers, while use of the recovery position mainly prevents aspiration of things like stomach content or blood. If head-tilt chin-lift and jaw-thrust maneuvers are performed with any objects in the airways it may dislodge them further down the airways and thereby cause more blockage and harder removal.

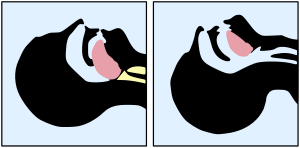

The head-tilt/chin-lift is the primary maneuver used in any patient in whom cervical spine injury is not a concern. The simplest way of ensuring an open airway in an unconscious patient is to use a head-tilt/chin-lift technique, thereby lifting the tongue from the back of the throat. The maneuver is performed by tilting the head backwards in unconscious patients, often by applying pressure to the forehead and the chin. Head-tilt/chin-lift is taught on most first aid courses as the standard way of clearing an airway.

The jaw-thrust maneuver is an effective airway technique, particularly in the patient in whom cervical spine injury is a concern. The jaw thrust is a technique used on patients with a suspected spinal injury and is used on a supine patient. The practitioner uses their index and middle fingers to physically push the posterior (back) aspects of the mandible upwards while their thumbs push down on the chin to open the mouth. When the mandible is displaced forward, it pulls the tongue forward and prevents it from occluding the entrance to the trachea.

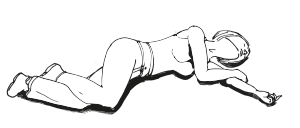

The recovery position refers to one of a series of variations on a lateral recumbent or three-quarters prone position of the body, in to which an unconscious but breathing casualty can be placed. Use of the recovery position prevents aspiration.

Most airway maneuvers are associated with some movement of the cervical spine.[5][6] Even though collars for holding the head in-line can cause problems maintaining an airway and maintaining a blood pressure,[7] it is unrecommended to remove the collar without adequate personnel to manually hold the head in place.[8]

See also

References

- Nolan, JP; Soar, J; Zideman, DA; Biarent, D; Bossaert, LL; Deakin, C; Koster, RW; Wyllie, J; Böttiger, B; ERC Guidelines Writing Group (2010). "European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 1. Executive summary". Resuscitation. 81 (10): 1219–1276. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.021. PMID 20956052.

- Foreign object inhaled: First aid, Mayo Clinic staff, Nov. 1, 2011.

- "Australian(and New Zealand) Resuscitation Council Guideline 4 AIRWAY". Australian Resuscitation Council (2010). Archived from the original on 2014-02-14. Retrieved 2014-02-09.

- American Medical Association (2009-05-05). American Medical Association Handbook of First Aid and Emergency Care. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-0712-7.

- Donaldson WF, Heil BV, Donaldson VP, Silvaggio VJ (1997). "The effect of airway maneuvers on the unstable C1-C2 segment. A cadaver study". Spine. 22 (11): 1215–8. doi:10.1097/00007632-199706010-00008. PMID 9201858.

- Brimacombe J, Keller C, Künzel KH, Gaber O, Boehler M, Pühringer F (2000). "Cervical spine motion during airway management: a cinefluoroscopic study of the posteriorly destabilized third cervical vertebrae in human cadavers". Anesth Analg. 91 (5): 1274–8. doi:10.1213/00000539-200011000-00041. PMID 11049921.

- Kolb JC, Summers RL, Galli RL (1999). "Cervical collar-induced changes in intracranial pressure". Am J Emerg Med. 17 (2): 135–7. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(99)90044-X. PMID 10102310.

- Mobbs RJ, Stoodley MA, Fuller J (2002). "Effect of cervical hard collar on intracranial pressure after head injury". ANZ J Surg. 72 (6): 389–91. doi:10.1046/j.1445-2197.2002.02462.x. PMID 12121154.

External links

| The Wikibook First Aid has a page on the topic of: Airway Management |