Bronchoscopy

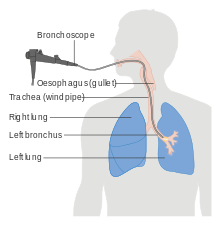

Bronchoscopy is an endoscopic technique of visualizing the inside of the airways for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. An instrument (bronchoscope) is inserted into the airways, usually through the nose or mouth, or occasionally through a tracheostomy. This allows the practitioner to examine the patient's airways for abnormalities such as foreign bodies, bleeding, tumors, or inflammation. Specimens may be taken from inside the lungs. The construction of bronchoscopes ranges from rigid metal tubes with attached lighting devices to flexible optical fiber instruments with realtime video equipment.

| Bronchoscopy | |

|---|---|

A physician performing bronchoscopy. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 33.21-33.23 |

| MeSH | D001999 |

| OPS-301 code | 1-62 |

| MedlinePlus | 003857 |

History

The German laryngologist Gustav Killian is attributed with performing the first bronchoscopy in 1897.[1] Killian used a rigid bronchoscope to remove a pork bone. The procedure was done in an awake patient using topical cocaine as a local anesthetic.[2] From this time until the 1970s, rigid bronchoscopes were used exclusively.

Chevalier Jackson, refined the rigid bronchoscope in the 1920s, using this rigid tube to visually inspect the trachea and mainstem bronchi.[3] The British laryngologist Victor Negus, who worked with Jackson, improved the design of his endoscopes, including what came to be called the "Negus bronchoscope".

Shigeto Ikeda invented the flexible bronchoscope in 1966.[4] The flexible scope initially employed fiberoptic bundles requiring an external light source for illumination. These scopes had outside diameters of approximately 5 mm to 6 mm, with an ability to flex 180 degrees and to extend 120 degrees, allowing entry into lobar and segmental bronchi. More recently, fiberoptic scopes have been replaced by bronchoscopes with a charge coupled device (CCD) video chip located at their distal end.[5]

Types

Rigid

The rigid bronchoscope is a hollow metal tube used for inspecting the lower airway. It can be for either diagnostic or therapeutic reasons. Modern use is almost exclusively for therapeutic indications. Rigid bronchoscopy is used for retrieving foreign objects.[6] Rigid bronchoscopy is useful for recovering inhaled foreign bodies because it allows for protection of the airway and controlling the foreign body during recovery.[7]

Massive hemoptysis, defined as loss of over 600 mL of blood in 24 hours, is a medical emergency and should be addressed with initiation of intravenous fluids and examination with rigid bronchoscopy. The larger lumen of the rigid bronchoscope (versus the narrow lumen of the flexible bronchoscope) allows for therapeutic approaches such as electrocautery to help control the bleeding.

Flexible (fiberoptic)

A flexible bronchoscope is longer and thinner than a rigid bronchoscope. It contains a fiberoptic system that transmits an image from the tip of the instrument to an eyepiece or video camera at the opposite end. Using Bowden cables connected to a lever at the hand piece, the tip of the instrument can be oriented, allowing the practitioner to navigate the instrument into individual lobar or segmental bronchi. Most flexible bronchoscopes also include a channel for suctioning or instrumentation, but these are significantly smaller than those in a rigid bronchoscope.

Flexible bronchoscopy causes less discomfort for the patient than rigid bronchoscopy, and the procedure can be performed easily and safely under moderate sedation. It is the technique of choice nowadays for most bronchoscopic procedures.

Indications

Diagnostic

- To view abnormalities of the airway

- To obtain tissue specimens of the inside the lungs by biopsy, bronchoalveolar lavage, or endobronchial brushing.

- To evaluate a person who has bleeding in the lungs, possible lung cancer, a chronic cough, or sarcoidosis

Therapeutic

- To remove secretions, blood, or foreign objects lodged in the airway

- Laser resection of tumors or benign tracheal and bronchial strictures

- Stent insertion to palliate extrinsic compression of the tracheobronchial lumen from either malignant or benign disease processes

- For percutaneous tracheostomy

- Tracheal intubation of patients with difficult airways is often performed using a flexible bronchoscope

Procedure

Bronchoscopy can be performed in a special room designated for such procedures, operating room, intensive care unit, or other location with resources for the management of airway emergencies. The patient will often be given antianxiety and antisecretory medications (to prevent oral secretions from obstructing the view), generally atropine, and sometimes an analgesic such as morphine. During the procedure, sedatives such as midazolam or propofol may be used. A local anesthetic is often given to anesthetize the mucous membranes of the pharynx, larynx, and trachea. The patient is monitored during the procedure with periodic blood pressure checks, continuous ECG monitoring of the heart, and pulse oximetry.

A flexible bronchoscope is inserted with the patient in a sitting or supine position. Once the bronchoscope is inserted into the upper airway, the vocal cords are inspected. The instrument is advanced to the trachea and further down into the bronchial system and each area is inspected as the bronchoscope passes. If an abnormality is discovered, it may be sampled using a brush, a needle, or forceps. Specimen of lung tissue (transbronchial biopsy) may be sampled using a real-time x-ray (fluoroscopy) or an electromagnetic tracking system.[8] Flexible bronchoscopy can also be performed on intubated patients, such as patients in intensive care. In this case, the instrument is inserted through an adapter connected to the tracheal tube.

Rigid bronchoscopy is performed under general anesthesia. Rigid bronchoscopes are too large to allow parallel placement of other devices in the trachea; therefore the anesthesia apparatus is connected to the bronchoscope and the patient is ventilated through the bronchoscope.

Recovery

Although most patients tolerate bronchoscopy well, a brief period of observation is required after the procedure. Most complications occur early and are readily apparent at the time of the procedure. The patient is assessed for respiratory difficulty (stridor and dyspnea resulting from laryngeal edema, laryngospasm, or bronchospasm). Monitoring continues until the effects of sedative drugs wear off and gag reflex has returned. If the patient has had a transbronchial biopsy, doctors may take a chest x-ray to rule out any air leakage in the lungs (pneumothorax) after the procedure. The patient will be hospitalized if there occurs any bleeding, air leakage (pneumothorax), or respiratory distress.

Complications and risks

Besides the risks associated with the drugs used, there are also specific risks of the procedure. Although a rigid bronchoscope can scratch or tear airways or damage the vocal cords, the risk of bronchoscopy is limited. Complications from fiberoptic bronchoscopy remain extremely low. Common complications include excessive bleeding following biopsy. A lung biopsy also may cause leakage of air, called pneumothorax. Pneumothorax occurs in less than 1% of lung biopsy cases. Laryngospasm is a rare complication but may sometimes require tracheal intubation. Patients with tumors or significant bleeding may experience increased difficulty breathing after a bronchoscopic procedure, sometimes due to swelling of the mucous membranes of the airways.

See also

References

- Panchabhai TS, Mehta AC. Historical perspectives of bronchoscopy. Connecting the dots. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015 May;12(5):631-41. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201502-089PS. PubMed PMID 25965540

- Kollofrath O. Entfernung Eines Knochenstucks Aus Dem Rechten Bronchus Auf Naturlichem Wege Und Unter Anwendung Der Directen Laryngoskopie. Munch Med Wochenschr 1897;38:1038-1039.

- https://archive.org/details/tracheobronchosc00jackuoft/page/n1

- Ikeda S, Tobayashi K, Sunakura M, Hatakeyama T, Ono R. [Diagnosis using a fiberscope--the respiratory organs]. Naika. 1969 Aug;24(2):284-91. Japanese. PubMed PMID 5352887.

- Kobayashi T, Koshiishi H, Kawate N, A. dela Cruz CM, Kato H. The Performance of Prototype Videobronchoscopes: The Pentax Eb-Tm1830 and Eb-Tm1530. Journal of Bronchology & Interventional Pulmonology 1994;1(2):160-167.

- Rick Daniels (15 June 2009). Delmar's Guide to Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests. Cengage Learning. pp. 163–. ISBN 978-1-4180-2067-5. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- Rosbe, Kristina W.; Burke, Kevin (2012). "Chapter 39. Foreign Bodies". In Lalwani, Anil (ed.). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment in Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery (3rd ed.). New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- Pall J. Reynisson et al. (2014). Navigated Bronchoscopy - A Technical Review. Interv Pulmonol. 21(3):242-264

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bronchoscopy. |