We need you! Join our contributor community and become a WikEM editor through our open and transparent promotion process.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding

From WikEM

(Redirected from Upper GI Bleed)

Contents

Background

- Bleeding originating proximal to ligament of Treitz

- In the acute setting, the hemoglobin/hematocrit may be normal until dilutional anemia appears after volume resuscitation

Prehospital

- Airway: suction to prevent aspiration, provide oxygen as needed

- Breathing: maintain patient is position of comfort

- Circulation: monitor for early signs of shock, and provide fluid resuscitation if hypotensive. Blood products should be individualized based on local protocols

- Antiemetics can be given to decrease nausea and vomitting

- Assume the patient is hepatitis positive and wear appropriate personal protective gear

Clinical Features

History

- Hematemesis

- Coffee-ground emesis

- Syncopy or pre-syncopy

- Melena + age <50 suggests upper GI bleed

- Vomiting + retching followed by hematemesis = Mallory-Weiss

- Dyspepsia, epigastric pain or heartburn

- Aortic graft = aortoenteric fistula

- Meds

- ETOH abuse

- Peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, varices

Physical Exam

- Tachycardia, hypotension

- Liver disease

- Spider angiomata, palmar erythema, jaundice, gynecomastia

- Coagulopathy

- Petechiae/purpura

- ENT exam

- Swallowed blood may result in coffee-ground emesis or melena

- Rectal exam

- Only 20% of patients with a positive fecal occult have an identified upper GI bleed. UGI Bleed should not be ruled out based on a negative test[1]

Differential Diagnosis

- Peptic ulcer disease (most common cause)

- Gastritis/esophagitis

- Gastric/esophageal varices

- Mallory-Weiss tear

- Malignancy

- Aortoenteric fisulta

- Boerhaave

- Dieulafoy's lesion

- Angiodysplasia

- Hemobilia

- Hemorrhagic gastritis, EtOH

- Celiac

- Dengue

- Other intrabdominal bleeds

- Hemorrhagic pancreatitis

- Splenic rupture

- Subcapsular cavernous hemangiomas

- Peliosis hepatis

Mimics of GI Bleeding

- Hemoptysis

- Vaginal/Urethra bleeding

- ENT bleeding

- Dietary (Iron, bismuth, beets)

Evaluation

Workup

- 2 large bore IVs

- Type and cross

- CBC & serial hemoglobin

- Chemistry

- BUN/creatinine >30 suggests UGI if no history of renal failure (increased absorption/digestion of hb)

- Coags

- LFTs

- Guiac

- ?ECG (if >50 yo or if suspicious for silent MI)

- ?CXR (if suspect perforation)

NG Lavage Controversy

- Pros[2]

- Positive aspirate proves strong evidence for an UGI source of bleeding

- Can assess presence of ongoing active bleeding

- Can prepare patient for endoscopy

- Cons[2]

- Uncomfortable

- Negative aspirate does not conclusively exclude UGI source

- Provides useful information in only minority of patients without hematemesis

- Erythromycin 200mg IV can provide equal endoscopy conditions as lavage[3]

Management

Resuscitation

- Place 2 large bore IVs and monitor airway status

Proton Pump Inhibitor

- Pantoprazole/esomeprazole 80mg x 1; then 8mg/hr

- Intermittent dosing of pantoprazole, esomeprazole, or omeprazole 40 mg IV BID not inferior to continuous infusion dosing[4]

- Reduces the rate of re-bleeding and need for surgery if there is an ulcer, but does not reduce morbidity or mortality[5]

- There is a mortality benefit in Asian patients[6]

Erythromycin

- Achieves endoscopy conditions equal to lavage[7]

- 3mg/kg IV over 20-30min, 30-90min prior to endoscopy

IVF

- Crystalloid can be used for initial resuscitation but should be limited due to the dilutional anemia and dilatational coagulopathy that can result

PRBC transfusions

In hemodynamically stable patients, the goal transfusion threshold should be 7 g/dl; NICE guidelines recommend avoidance of over-transfusion[8]

Indications:

- Hemoglobin <7 g/dl

- Continued active bleeding

- Failure to improve perfusion and vital signs after infusion of 2L NS

- Varicele bleeding[9]

Other Blood Products

- Prothrombin complex concentrates[10]

- Cryopprecipitate to raise fibrinogen (goal >120mg/dL)

- Platelets (goal >50-100k/μL

- FFP can be used to correct anticoagulated patients, but is not indicated in cirrhotics with variceal bleeding[11]

Endoscopy

- Endoscopy should be performed at the discretion of the gastroenterologist; within 12 hrs for variceal bleeding[12]

Early endoscopy does not necessarily improve clinical outcomes[13]

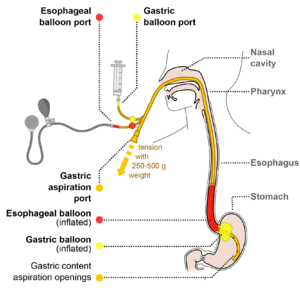

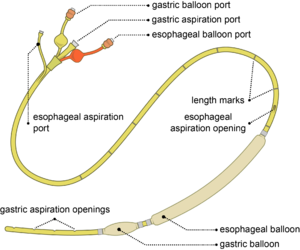

Balloon tamponade with Sengstaken-Blakemore Tube

- For life-threatening hemorrhage if endoscopy is not available

- Tube consists of gastric and esophageal balloons

- First inflate gastric balloon; if bleeding continues inflate esophageal balloon

- Esophageal pressure must not exceed 40-50 mmHg

- First inflate gastric balloon; if bleeding continues inflate esophageal balloon

- Adverse reactions are frequent

- Mucosal ulceration

- Esophageal/gastric rupture

- Tracheal compression (consider intubation prior to balloon insertion)

Special Circumstances

- Acute variceal bleeding

- Octreotide (50 mcg IV bolus, then 50 mcg/hr continuous, maintained at 2-5 days)[14]

- Judicious IVF and blood products

- Emergency endoscopy for ligation, banding, and/or sclerotherapy

- Antibiotics

- For short-term prophylaxis against SBP and bacteremia[15]

- Recommend administering antibiotics prior to endoscopy or as soon as possible after endoscopy

- Ciprofloxacin IV or PO 500mg BID x7 days

- OR ceftriaxone 1gm daily x 7 days

- Indicated for patients with cirrhosis or history of ETOH abuse (regardless of whether bleeding is variceal or not)

- More effective than quinolones[16]

- Vasopressin associated with many vasoconstrictive complications to include peripheral necrosis, dysrhythmias, myocardial ischemia [17]

- 0.4 unit bolus, then infuse at 0.4 - 1 unit/min[18]

- Give with IV nitroglycerin at 10 - 50 mcg/min to bolster portal hypotension and reduce vasopressin systemic effects[19]

- Terlipressin (analog of vasopressin, available outside U.S.)

- Alternative to vasopressin with mortality benefit

- Given as 2mg IV q4 hrs, then decrease to 1mg IV q4 hrs until bleeding stops[20]

- No evidence for tranexamic acid (TXA); HALT-IT trial RCT underway[21]

Intubation

- Protection of airway from massive aspiration, especially prior to endoscopy

- Does not seem to protect against pneumonia or cardiopulmonary events[22]

- Have bed-side push-dose pressors on hand

- NO CHRISTMAS[23]

- NGT (salem sump to remove stomach contents)

- Varices not contraindication to NGT

- Consider metoclopramide 10mg IV

- Good pre-Oxygenation critical

- Chest and HOB elevation to 45 degrees - consider intubating from 45 degrees to prevent gastric contents coming up

- RSI - consider halving dosages for lost blood volume

- Etomidate or ketamine for sedation

- Succinylcholine and vecuronium increases LES tone

- Intubation with strong chance for first pass

- Slow and gentle BVM breathes at 10 breathes/min if first pass fails

- Trendelenberg if vomiting, keeping emesis out of lungs (have many suctions available before this happens)

- Meconium aspirator may be hooked up to ETT for large bore suction

- Antibiotics not needed in early phase of aspiration

- Chemical pneumonitis in first 24 hours, no bacterial pneumonia

- Early antibiotics may predispose patient to resistant bacterial superinfection

- SIRS-like response often occurs from aspiration, but otherwise not sepsis if there is no other concerning source or suspicion

- May require pressors and fluids

- Consider withholding early antibiotics, but doing the rest of the sepsis treatments

- NGT (salem sump to remove stomach contents)

Disposition

Admission

- Age >60yr

- Transfusion required

- Initial Sys BP < 100

- Red blood in NG lavage

- History of cirrhosis or ascites on exam

- History of vomiting red blood

Consider Discharge

If Glasgow-Blatchford Bleeding Score of 0 (<1% chance of requiring intervention):[24]. Must meet ALL of the following:

- BUN <18

- hemoglobin >13 (men), hemoglobin >12 (women)

- Sys BP >110

- HR <100

- Patient did NOT present with melena

- Patient did NOT present with syncope

- No hepatic disease

- No cardiac failure

See Also

- Lower GI Bleeding

- Upper GI Bleed Guidelines

- Balloon tamponade

- EBQ:Omeprazole in Bleeding Peptic Ulcers

References

- ↑ Allard J et al. Gastroscopy following a positive fecal occult blood test and negative colonoscopy: systematic review and guideline. Can J Gastroenterol.2010;24(2):113-120.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Aljebreen AM et al. Nasogastric aspirate predicts high-risk endoscopic lesions in patients with acute upper-GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(2):172-178.

- ↑ Huang ES et al. Impact of nasogastric lavage on outcomes in acute GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(5):971-980.

- ↑ Sachar H, Vaidya K, Laine L. Intermittent vs continuous proton pump inhibitor therapy for high-risk bleeding ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1755.

- ↑ Leontiadis GI et al. Proton pump inhibitor treatment for acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004(3):CD002094.

- ↑ Singh M. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) given for acute peptic ulcer bleeding 2013; bleeding/

- ↑ Pateron D, et al. Erythromycin infusion or gastric lavage for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2011; 57(6):582-589.

- ↑ Dworzynski K et al. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2012;344:e3412.

- ↑ Intagliata NM, et al. Management of disordered hemostasis and coagulation in patients with cirrhosis. Clinical Liver Disease. 2014; 3(6):114-117.

- ↑ Makris M, et al. Warfarin anticoagulation reversal: management of the asymptomatic and bleeding patient. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010; 28:171–181.

- ↑ Intagliata NM, et al. Management of disordered hemostasis and coagulation in patients with cirrhosis. Clinical Liver Disease. 2014; 3(6):114-117.

- ↑ Kim YD. Management of acute variceal bleeding. Clin Endosc. 2014; 47(4):308–314.

- ↑ Sarin N et al. Time to endoscopy and out- comes in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23(7):489-493.

- ↑ Augustin S et al. Acute esophageal variceal bleeding: Current strategies and new perspectives. World J Hepatol. 2010 Jul 27; 2(7): 261–274.

- ↑ Lee YY et al. Role of prophylactic antibiotics in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Feb 21; 20(7): 1790–1796.

- ↑ Fernandez J, Ruiz dA, Gomez C, et al. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1049–1056.

- ↑ GI Bleeding: An Evidence-Based ED Approach. EB Medicine. http://www.ebmedicine.net/topics.php?paction=showTopicSeg&topic_id=75&seg_id=1507

- ↑ Ioannou G, Doust J, Rockey DC. Terlipressin for acute esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003:CD002147.

- ↑ Tsai YT, Lay CS, Lai KH, et al. Controlled trial of vasopressin plus nitroglycerin vs. vasopressin alone in the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices. Hepatology 1986; 6:406.

- ↑ Ioannou G, Doust J, Rockey DC. Terlipressin for acute esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003:CD002147.

- ↑ Roberts I et al. HALT-IT - tranexamic acid for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014; 15: 450.

- ↑ Rudolph SJ et al. Endotracheal intubation for airway protection during endoscopy for severe upper GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003 Jan;57(1):58-61.

- ↑ Weingart S. EMCrit Podcast 5 – Intubating the Critical GI Bleeder. June 2009. http://emcrit.org/podcasts/intubating-gi-bleeds/

- ↑ Tacke F, Fiedler K, Trautwein C. A simple clinical score pre- dicts high risk for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages from varices in patients with chronic liver disease. Scand J Gastro- enterol. 2007;42(3):374-382.