Hispanics/Latinos and Tobacco Use

Hispanic or Latino is defined by the Office of Management and Budget as “a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race.”1

In the United States, there are more than 55 million people of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity.2 This group makes up approximately 17% of the current estimated population, and is expected to comprise nearly 30% of the U.S. population by the year 2060.3

Hispanic/Latino adults generally have lower prevalence of cigarette smoking and other tobacco use than other racial/ethnic groups, with the exception of Asian Americans.4,5 However, prevalence varies among sub-groups within the Hispanic population.6,7

Tobacco Use Prevalence

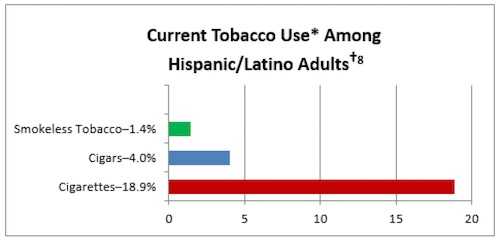

20.9% of Hispanic/Latino adults reported current use* of tobacco in 2013.8

- Prevalence of cigarette smoking is higher among Hispanic adults born in the United States than those who were foreign-born.5

Cigarette smoking prevalence varies by Hispanic/Latino sub-groups:9

| Hispanic/Latino Sub-Group | Prevalence§9 |

|---|---|

| Puerto Rican | 28.5% |

| Cuban | 19.8% |

| Mexican | 19.1% |

| Central or South American | 20.2% |

* “Current Use” is defined as self-reported consumption of cigarettes, cigars, or smokeless tobacco in the past month.

† Data taken from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2013, and refer to Hispanic/Latino Americans aged 18 years and older.

§ Prevalence data for Hispanic/Latino sub-groups taken from NSDUH, 2010–2013, and include persons aged 18 years and older who reported smoking cigarettes during the past month.

Health Effects

Cancer, heart disease, and stroke—all of which can be caused by cigarette smoking—are among the five leading causes of death among Hispanics.5,10,11

- Diabetes is the fifth leading cause of death among Hispanics.5 The risk of developing diabetes is 30–40% higher for cigarette smokers than nonsmokers.12

Patterns of Tobacco Use

Variations in cigarette smoking exist among different Hispanic subgroups.

- Number of cigarettes smoked per day is highest among Cuban daily smokers than daily smokers within other Hispanic/Latino groups.13

- 50% of Cuban men and more than 35% of Cuban women report smoking 20 or more cigarettes per day.13

- Mexican men and women are less likely than other Hispanic/Latino groups to report that they smoke 20 or more cigarettes per day.13

- Intermittent current cigarette smoking (smoking only some days in the past month) is most common among Mexican men—15.5% compared to 9.8% of Central American men, 9% of Puerto Rican men, and 4.9% of Cuban men.13

- Hispanic women (with the exception of Puerto Rican women) generally have low prevalence of cigarette smoking during pregnancy.14

Secondhand Smoke Exposure

During 2011–2012, nearly 58 million people were exposed to secondhand smoke in the United States, including 6.2 million Mexican American nonsmokers.15

During 2011–2012:

- 29.9% of Mexican-American children aged 3–11 years were exposed to secondhand smoke.15

- 16.9% of Mexican-American adolescents aged 12–19 years and 23.8% of Mexican-American adults aged 20 years and older were exposed to secondhand smoke.15

Quitting Behavior

- Among Hispanic current daily cigarette smokers aged 18 years and older:

- An estimated 58.4% report that they want to quit compared with 74.1% of African Americans, 69.4% of whites, 63.3% of Asians, and 52.1% of American Indians/Alaska Natives.12

- An estimated 51.8% report attempting to quit in the past year compared with 49.3% of African Americans, 40.9% of whites, and 39.4% of Asians.12

Hispanics/Latinos have lower health insurance coverage and less healthcare access than whites, making it less likely that they will be advised by a health care provider to quit smoking cigarettes or to have access to cessation treatments.5

Tobacco Industry Marketing and Influence

Tobacco products are advertised and promoted disproportionately to racial/ethnic minority communities. Tobacco companies seek to appeal to the Hispanic population through branding, financial contributions, and targeted advertising.7

- Historically, cigarette brand names such as “Rio” and “Dorado” have been heavily advertised and marketed to the Hispanic-American community, including advertisements in many Hispanic publications.7

- The tobacco industry has contributed to programs that enhance education of young people, such as funding universities and colleges and supporting scholarship programs targeting Hispanics.7

- The tobacco industry has also provided significant support to Hispanic political organizations, cultural events, and the Hispanic art community.7,16

Culturally appropriate anti-smoking health marketing strategies and mass media campaigns like CDC’s Tips From Former Smokers national tobacco education campaign, as well as CDC-recommended tobacco prevention and control programs and policies, can help reduce the burden of disease among the Hispanic/Latino population.

Resources

Publications

- A Look at Smoking Among Hispanic Americans [PDF–79 KB]

- American Cancer Society: Guide to Quitting Smoking

Websites

Special Publication

Disparities in Adult Cigarette Smoking—United States, 2002–2005 and 2010–2013

Although cigarette smoking has declined significantly since the release of the 1964 Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health, disparities in tobacco use varies among racial/ethnic populations. Moreover, estimates of U.S. adult cigarette smoking and tobacco use are usually limited to aggregate racial or ethnic population categories (non-Hispanic whites (whites), non-Hispanic blacks or African Americans (blacks), American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs), Asians, Native Hawaiians or Pacific Islanders (NHPI), and Hispanics/Latinos; these estimates can mask differences in cigarette smoking prevalence among subgroups of these populations.

References

- Government Printing Office. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, 1997 [PDF–156 KB]. [accessed 2017 Mar 1].

- U.S. Census Bureau. Population Estimates, 2015 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014–2060 [PDF–1.16 MB]. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau, 2015 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults, United States—2012–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2014:63(25);542–7 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Leading Causes of Death, Prevalence of Diseases and Risk Factors, and Use of Health Services Among Hispanics in the United States—2009–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2015;64(17):469–78 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Caraballo RS, Yee SL, Gfroerer J, Mirza S. Adult Tobacco Use Among Racial and Ethnic Groups Living in the United States 2002–2005 [PDF–447 KB]. Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy 2008;5(3):1–6 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, Table 2.21B. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2014 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disparities in Adult Cigarette Smoking—United States, 2002-2005 and 2010-2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2016;65(30) [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Heron, M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2010 [PDF–5.08 MB]. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2013;62(6) [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: Final Data for 2012 [PDF–2.12 MB]. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2013;63(9) [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Kaplan RC, Bangdiwala SI, Barnhart JM. Smoking Among U.S. Hispanic/Latino Adults: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2014;46(5):496–506 [cited 2016 Aug 10].

- American Lung Association. Hispanics. Chicago: American Lung Association, 2010 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Disparities in Nonsmokers’ Exposure to Secondhand Smoke—United States 1999–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2015;64(Early Release):1–7 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Tobacco Use and Hispanics [PDF–135 KB]. Washington, D.C.: Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, 2015 [accessed 2016 Aug 10].

For Further Information

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Office on Smoking and Health

E-mail: tobaccoinfo@cdc.gov

Phone: 1-800-CDC-INFO

Media Inquiries: Contact CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health press line at 770-488-5493.

- Page last reviewed: September 18, 2017

- Page last updated: September 18, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir