Key Findings: Persistence of Parent-Reported Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms from Childhood through Adolescence in a Community Sample

The Journal of Attention Disorders has published a study: “Persistence of Parent-Reported Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms from Childhood through Adolescence in a Community Sample.” Researchers from CDC and the University of South Carolina used information from the Project to Learn about ADHD in Youth (PLAY) to learn more about the symptoms and the course of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms in children. The study found that as children got older, parents reported fewer ADHD symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity (for example, fidgeting, interrupting), but continued to report inattentive symptoms (for example, being forgetful or easily distracted) into adolescence. Therefore, families living with ADHD and clinicians should be aware that certain ADHD symptoms can often last into adolescence. Learn about the main findings from the research.Read the abstract.

Main Finding from this Study

What was the goal of this study?

This study looked at PLAY data from parents who reported that their children had certain symptoms of ADHD (inattention and hyperactivity or impulsivity) to learn whether the ADHD symptoms persist from early childhood through late adolescence.

What were the study results?

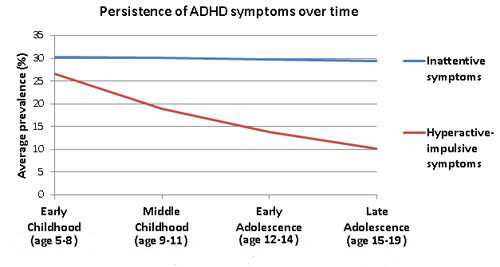

- Parents were similarly likely to report inattentive (30%) and hyperactive or impulsive (hyperactive-impulsive; 27%) symptoms in their children during early childhood, but were less likely to report hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms as children reached late adolescence. Parents’ report of inattention remained consistent as the child aged.

- The proportion of children with a high number of inattentive symptoms was similar across age groups, from young childhood to late adolescence.

- The proportion of children with a high number of hyperactive-impulsive symptoms decreased with age. This was also true after taking into account the child’s sex, ADHD medication use, and whether they had a co-occurring psychiatric disorder.

- Children who had many hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were more likely to continue having these symptoms as teenagers if they also had many inattentive symptoms.

About Play

PLAY is a population-based project that screens schoolchildren for mental and behavioral problems and then invites some of these children in for a diagnostic evaluation. The goal of this project is to learn more about children with ADHD, the prevalence, causes, co-occurring conditions, risks, and treatment of ADHD among school-aged children. Two PLAY study sites followed children from elementary school (age 5-13 years) through adolescence (up to age 19) to investigate the short and long-term outcomes of children with ADHD. These studies provide information on ADHD symptoms and diagnosis and track children’s development over time. Using a community-based approach (for example, looking at children in schools) makes it possible to find children who are likely to have ADHD, but have not yet been diagnosed with the condition, and helps us learn more about the development of children with ADHD over time.

As other studies have shown, more boys had ADHD symptoms than girls. However, this study was able to show that over time, the number of symptoms appears to be steady for both boys and girls. That is, girls who had a number of symptoms when they were young were as likely as boys to continue to have those symptoms after they became teenagers.

What are the implications for children with ADHD?

The findings show the importance for healthcare providers and parents to pay close attention to a child’s ADHD symptoms from childhood throughout adolescence. Even if hyperactive-impulsive symptoms decrease, inattentive symptoms can persist. Like hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, inattentive symptoms can cause difficulty at school, at home, or with friends, and later with work.

ADHD and CDC’s Work

CDC monitors the number of children who have been diagnosed with ADHD through the use of national survey data. Including questions about ADHD on national or regional surveys helps us learn more about the number of children with ADHD, their use of ADHD treatments, and the impact of ADHD on children and their families.

CDC also conducts community-based studies to better understand the impact of ADHD and other mental and behavioral health conditions. The Project to Learn about ADHD in Youth (PLAY) study methods have been implemented in four community sites. Information from the PLAY study helps us better understand ADHD and other mental and behavioral disorders, as well as the needs of children and families living with these conditions.

CDC supports the National Resource Center on ADHD, a program of Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD), which is a Public Health Practice and Resource Center. Their web site (http://www.help4adhd.org/NRC.aspx) has information based on the best medical evidence about the care for people with ADHD and their families. The National Resource Center operates a call center with trained, bilingual staff to answer questions about ADHD. Their phone number is 1-800-233-4050.

More Information

To learn more about ADHD and CDC’s work in the area of ADHD, please visit https://www.cdc.gov/adhd

Glossary

Diagnostic evaluations ask questions about symptoms of ADHD and how children function in school and in daily activities.

Prevalence of ADHD among children is the number of children with ADHD compared to the total number of all children

Co-occurring conditions are other conditions such as anxiety, depression, and learning disabilities that children may have in addition to ADHD.

- Page last reviewed: September 7, 2017

- Page last updated: September 7, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir