Key Findings: Using Different Diagnosis Criteria for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) to Help Determine How Many Children Have the Disorder

The Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has published a study, The Impact of Case Definition on ADHD Prevalence Estimates in Community-Based Samples of School-Aged Children, looking at the difference in the estimated percentage of children who have Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) when the condition is defined in different ways. Researchers from the CDC, the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, and the University of South Carolina found that the estimates of ADHD prevalence vary greatly by which ADHD criteria are applied.

Data from the Project to Learn about ADHD in Youth (PLAY) was used to examine the impact of using different diagnostic criteria to estimate the prevalence of children with ADHD. The researchers did this in two ways. First, they estimated the percentage of children aged 4 to 13 years who meet criteria for ADHD using the most recent version of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth edition (DSM-5). Secondly, they estimated the percentage of children who meet criteria using the older DSM Fourth edition (DSM-IV).

Read an abstract of the article.

Main Findings

The DSM-5 diagnostic guidelines require

- 6 or more symptoms that appear before age 12,

- Symptoms cause impairment in more than one setting (e.g., home and school), and

- More than one type of person observes and reports on the child’s symptoms (e.g., parent and teacher).

Often all of the criteria are not used, but as the results of this study showed, using only some of the criteria clearly has an effect on the estimated prevalence.

The percentage of children (4-13 years old) meeting criteria for ADHD was higher if the DSM-5 criteria are used than if the DSM-IV criteria are used (11% versus 9%) because the age of onset of symptoms requirement was changed from being less than 7 years old to being less than 12 years old.

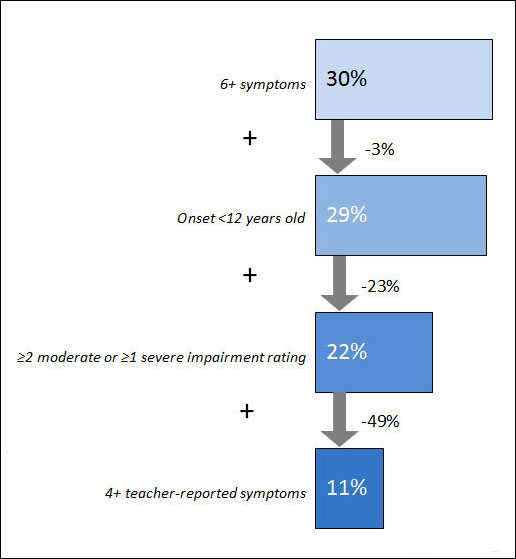

There was a steady decrease in estimated prevalence as more diagnostic criteria were used.

- Nearly 1 in 3 children (30%) had ADHD if a parent reported 6 or more symptoms of ADHD.

- 1 in 5 children (22%) had ADHD if researchers also included those who had the symptoms by age 12 years and showed functional impairment.

- 1 in 9 children (11%) had ADHD if researchers required that a teacher also reports symptoms—further reducing the estimated prevalence of ADHD by half.

Applying each DSM-5 criterion reduces the percentage of children aged 4-13 years who fit diagnostic criteria for ADHD

Main Findings Implications

- Clinicians need to be aware of the findings because they show that differences in how criteria are used to diagnose ADHD can affect how many children are diagnosed.

- Parents need to be aware of the findings because ADHD is complex and can be difficult to assess and diagnose; parents who have concerns about a child with behavioral problems should seek treatment from an experienced professional who can conduct a thorough evaluation.

- Researchers need to be aware of the findings because they show that some common ways of collecting information from parents and teachers on children’s’ behaviors can result in important differences in numbers children thought to have ADHD.

About this Study

- The primary goal of this study was to learn more about the impact on the estimated prevalence of ADHD by using different criteria to diagnose ADHD, and the effects of using the new DSM-5 criteria as opposed to the previous DSM-IV criteria on a previously described community group of children with ADHD.

- Data for this study are from the Project to Learn about ADHD in Youth (PLAY), a community-based study conducted in six school districts in South Carolina and Oklahoma.

- Teachers in the selected schools described ADHD symptoms on all the children in their classrooms. Researchers then selected a sample of children with many symptoms of ADHD, as well as a sample of children with few or no symptoms, and asked parents for a more in-depth assessment.

ADHD and CDC’s Work

CDC monitors the number of children who have been diagnosed with ADHD through the use of national survey data. Including questions about ADHD on national or regional surveys helps us learn more about the number of children with ADHD, their use of ADHD treatments, and the impact of ADHD on children and their families.

CDC also conducts community-based studies to better understand the impact of ADHD and other mental and behavioral health conditions. The Project to Learn about ADHD in Youth (PLAY) study methods have been implemented in four community sites. Information from the PLAY study helps us better understand ADHD and other mental and behavioral disorders, as well as the needs of children and families living with these conditions.

CDC supports the National Resource Center on ADHD, a program of Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD), which is a Public Health Practice and Resource Center. Their website has information based on the best medical evidence about the care for people with ADHD and their families. The National Resource Center operates a call center with trained, bilingual staff to answer questions about ADHD. Their phone number is 1-800-233-4050.

More Information

To learn more about ADHD and CDC’s work in the area of ADHD, please visit https://www.cdc.gov/adhd

Key Findings Reference

McKeown, R.E., Holbrook, J.R., Danielson, M.L., Cuffe, S.P., Wolraich, M.L., Visser, S.N. The Impact of Case Definition on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Prevalence Estimates; J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54(1):53–61.

Additional References

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. Arlington, VA., American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- Page last reviewed: September 7, 2017

- Page last updated: September 7, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir